News

Follow NUS Press on

International Women's Day 2017 March 8, 2017 15:23

Will you #BeBoldForChange on International Women's Day 2017? This year’s campaign calls for action to drive change and progress for women and create a “more gender inclusive” working world. This comes in light of recent projections by the World Economic Forum that—with the current state of affairs—the gender gap in workplaces will not close entirely until 2186.

In line with this year's theme, we have foregrounded women who have moved beyond the stifling limitations of gender norms and become leaders in their own right to enact groundbreaking change for their communities.

First on our list is Ann Wee (author of A Tiger Remembers: The Way We Were in Singapore), the founding mother of social work in Singapore. In 1955, she became a training office at the Social Welfare Department, responsible for counseling low-income families in their homes.

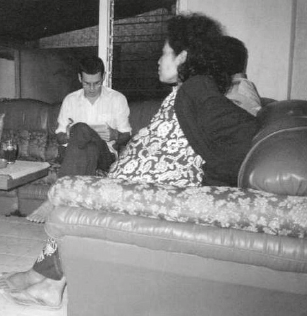

(Image courtesy of Ann Wee)

Later, Wee helped shape social work education in Singapore for undergraduates, establishing an Honours degree course for social workers. Responding to a question of what inclusivity means to her, Wee said, “(The) gender gap will close more easily if society emphasises 'parenthood' rather than just 'motherhod'. Inclusivity must include an ethos that not only gives men legal family rights, but makes it okay for them to exercise these rights.”

In the academic discipline of art history, we chatted with Sarah Tiffin, author of Southeast Asia in Ruins: Art and Empire in the Early 19th Century, who talked about female art historians she admired and their contributions to this field: “I remember that as an undergraduate in my first year of an art history degree, the work of Marcia Pointon, Linda Nochlin and Griselda Pollock was a revelation to me. Their writings taught me how to think critically, how to probe for the subtle undercurrents of meaning that lie hidden within an image. Instead of just looking at what was depicted, they taught me to ask how and why.”

(Image courtesy of Sarah Tiffin)

Shifting our perspective to a historical one, nationalist movements within Southeast Asia tend to adopt a male centric perspective. We read about the struggles of national heroes (usually male) against imperialism and their journeys to becoming the founders of Southeast Asian nation-states. Yet, little attention is given to the role of women who toiled alongside their male counterparts.

Susan Blackburn and Helen Ting’s edited volume, Women in Southeast Asian Nationalist Movements provides a more in-depth appreciation of such hidden figures. We have put the spotlight on two key figures:

Daw San (Burma)

“Daw San”, the pen name of Ma San Youn, was a pioneering nationalist in colonial Burma. Single handedly running the popular weekly newspaper Independent Weekly as an editor and author, Daw San was known for her prolific writings, which often underscored her nationalist and feminist aspirations. Partaking in local and trans-local women’s movements, she sought to make the Burmese government and political elites more accountable to the masses.

Suyatin Kartowiyono (Indonesia)

Remembered as the leader of the women’s movement in Indonesia, Suyatin Kartowiyono organized the first Indonesian women’s congress and became the founder of the secular women’s organization Perwari. Devoting herself to the burgeoning women’s movement and nationalist movement, she became a leader in raising women’s awareness of belonging within the Indonesian nation, demanding for radical changes in Indonesian society and public policy.

For more books on/about women and their social, political and cultural impact, check out our selection of titles. Happy International Women’s Day!

Five Minutes with Ronald McCrum February 24, 2017 10:00

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the Fall of Singapore. Considered one of the greatest defeats in the history of the British Army during World War Two, retired British Army Officer and military historian, Ronald McCrum, undertakes a close examination of the role and the responsibilities of the colonial authorities in his new book, The Men Who Lost Singapore, 1938-1942.

Considered one of the greatest defeats in the history of the British Army during World War Two, retired British Army Officer and military historian, Ronald McCrum, undertakes a close examination of the role and the responsibilities of the colonial authorities in his new book, The Men Who Lost Singapore, 1938-1942.

In this edition of Five Minutes With ..., we talk to Colonel McCrum to get his insights on how his military background helped his research, his history and ties with Southeast Asia, and whether co-ordination between civil authorities and military bodies has improved nearly eight decades on.

How did you come to be interested in the military history of this particular region?

My interest in military history was, I suppose, inevitable. At 18 years of age, I decided to become a soldier and at Sandhurst, the officer training college, part of the curriculum is military history and it fascinated me. In any case, it was now my chosen profession and I almost felt duty bound to understand something of the trials and tribulations of my predecessors.

The Far East, Malaya/Malaysia and Singapore were of particular interest because I spent a lot of my life in these parts. I first came to the area not long after the end of the war (1948/49?)—my father was then stationed in Nee Soon. We lived just outside Johor Bahru and I went to ‘English College’ in Johor Bahru. After a period in England, we returned to Malaya, this time to Kuala Lumpur (KL) and I went to Victoria Institution in KL. So the formative years of my life were in this part of the world.

McCrum in Germany (Iserlohn), 1981

(Image credit: Ronald McCrum)

In your book you discuss the various factors leading up to Singapore’s downfall, particularly how the preparation and execution of British defence strategies were addled by the conflicting views, interests and priorities of the military and civil authorities. In what ways has your military experience allowed you to be more attuned to these issues?

In 1965, after I had been a commissioned officer in the British Army for a number of years, an opportunity arose to be seconded for a period to the Malaysia Armed Forces and I accepted. I was sent to the Malaysian Military College at Sungei Besi just outside KL as an instructor. While in Malaysia my first two sons were born, the first shortly after we arrived and the second just before we returned to UK. And then surprisingly in 1970 after completing a year’s course at the British senior officers Staff College I was sent to Singapore as the Assistant Defence Advisor to the British High Commissioner. Where I spent two and half very happy years and my third and last son was born there. All three boys have Southeast Asia in their blood.

You’ve pointed out the civil authorities were slow to recognise the impending threat of the Japanese invasion. Was this general across other European colonies in Southeast Asia, or was it particular to Singapore? Do you think issues of co-ordination between civil authorities and military bodies improved with the advent of new technologies and procedures of co-ordination today?

While in Malaysia/Singapore I was endlessly curious about how the British Forces were so easily beaten in 1941/42. And in my travels I took the chance to visit the scenes of the battles that took place. After much reading, I began to recognise that in those early days of a new form of mobile modern warfare no one escaped an enveloping invasion. Inclusive lessons of total war were quickly learnt in the West, but in the quiet backwater of South East Asia such a prospect seemed remote. Glaringly obvious afterwards was the need for a combined (civil and military) planning headquarters, with an overall supremo able to impose decisions. At that time the three military services had each their own HQ’s in different locations in Singapore and the Governor was remote in Government House. Now of course a combined planning authority is normal greatly helped, of course, by modern communications. I cannot think of a current example where the civil and military authorities do not work closely together towards a common aim. A good instance in the Far East, after the war, was the combined operations of all the authorities in Malaya planning the defeat of the communist terrorists during the Malayan Emergency.

McCrum in Israel, 1988

(Image credit: Ronald McCrum)

What also struck me as grossly negligent was the poor, indeed almost non-existent, liaison between the Colonial Office and the War Office in London. One was demanding increased production of tin and rubber and the other telling the military they had to employ local labour to prepare defences. The same labour that was required on the rubber estates and the tin mines. There were of course a number of other very important factors that played a crucial part in the defeat, but the authorities quarrelling on basic matters like this did not help.

What are your future plans? Are you thinking of writing another book?

I am well into researching another book. This time a biography of a significant British figure who played an important part during the Indian Mutiny of 1857.

McCrum in Singapore with an advance copy of

The Men Who Lost Singapore in early February 2017

(Image credit: Pallavi Narayan)

#BuySingLit Highlights (Part 3) February 23, 2017 14:30

In the third installment of our series on #BuySingLit highlights, we look at memoirs written by Singapore authors. Through the memoirs published here at NUS Press, the experiences and personal anecdotes shared by authors have allowed readers to learn more about their outlook on life and the world around them.

Here is a short reading list that gives you glimpses of Singapore and the wider world through different lives that have been lived.

|

From the Blue Windows: Recollections of Life in Queenstown, Singapore, in the 1960s and 1970s

By Tan Kok Yang Have you ever wondered what everyday life was like in one of the earliest housing estates in Singapore during the 1960s and 1970s? In From the Blue Windows, Tan Kok Yang reminisces about life during his formative years in Queenstown. Coupled with a sense of nostalgia, Tan’s memoir pays tribute to the estate he grew up in and takes readers back to a simpler time of Singapore’s bygone past. |

|

|

A Tiger Remembers: The Way We Were in Singapore Born in the Year of the Fire Tiger, Ann Wee arrived in Singapore in 1950 to marry into a Singaporean Chinese family. Affectionately observed and wittily narrated, A Tiger Remembers recounts her experiences of cross-cultural learning such as domestic rituals and emotional nuances in social relations, along with various untold stories of Singapore’s past. With a strong appreciation for Singapore’s social transformation, this book provides a frank perspective on the shapes and forms of the Singapore family through the eyes of a keen social observer. |

|

|

Tall Tales and MisAdventures of a Young Westernized Oriental Gentleman What transpires when a young Asian student finds himself in the Ireland of the 1950s? This memoir by Singaporean novelist Goh Poh Seng details his adventures as a student in a world with an entirely different milieu and culture. Through his travels in Europe and stay in Dublin, readers are able to catch a glimpse of what shaped Goh to become the writer he is known as today. |

|

#BuySingLit Highlights (Part 2) February 22, 2017 10:00

In part 2 of our series on #BuySingLit highlights, we shift our attention to the discipline of Sociology. In the words of C Wright Mills, “neither the life of an individual nor the history of a society can be understood without understanding both”. Within the local context, Singapore society provides compelling subject matters for sociological inquiry given its metamorphosis since independence.

Here are two NUS Press titles that offer in-depth perspectives of specific social phenomena in Singapore.

|

Remembering the Samsui Women: Migration and Social Memory in Singapore and China

By Kelvin E.Y. Low Leaving their families behind and migrating from the Samsui region of Guangdong, China for a better life abroad, how did the Samsui women come to be icons of Singapore’s burgeoning economic transformation? How were these women, who donned the iconic “red head scarf” (红头巾), remembered for their hard work and sacrifices both in Singapore and China? Situated in the politics of social memory and the processes of remembering and forgetting, Kelvin Low explores first hand accounts of the women’s migratory experiences and how they were ultimately reinvented as industrious pioneers of Singapore through the memory appropriation of the Samsui women. |

|

|

The AWARE Saga: Civil Society and Public Morality in Singapore After the Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE) was helmed shortly by a Christian faction in March 2009, the controversy foregrounded issues such as religion, sex education, homosexuality, and state intervention within Singapore’s civil society. In this book, academics and public intellectuals situate the AWARE saga within the country’s political and historical context, further discussing the role of religion in Singapore’s civic society. |

|

#BuySingLit Highlights (Part 1) February 21, 2017 10:00

NUS Press is proud to take part in the #BuySingLit campaign, the first nationwide initiative led by the local publishing industry to promote the reading and purchasing of Singapore literature. In addition to discounts on selected titles available on our web store, we are also highlighting literary and non-fiction titles in a series of blog posts throughout the week.

Our first installment showcases the Press’s literary publications.

|

The Collected Poems of Arthur Yap By Arthur Yap, with an introduction by Irving Goh Sometimes referred to as a “poet’s poet,” Arthur Yap (1943–2006) published four major collections between 1971 and 1986, all of which are now out-of-print. With color reproductions of original cover art, many of which are Yap’s own paintings, and a critical introduction by Irving Goh, this volume of collected poems represents the burgeoning of recent scholarly activity surrounding his oeuvre. |

|

|

Noon at Five O’Clock: The Collected Short Stories of Arthur Yap For the first time ever, the rarely-seen short stories of Arthur Yap are brought together in a single volume of collected work. These short stories are less sprawling tales than miniature vignettes—or what Shirley Geok-lin Lim calls “his little area of animation”—all of which proffer glimpses into a mind constantly grappling with the aesthetics of global modernism with the lived experiences of modernity in a newly independent Singapore. |

|

|

If We Dream Too Long Widely regarded as the first Singapore novel, If We Dream Too Long explores the dilemmas and challenges faced by its hero, Kwang Meng, as he navigates the difficult transitional period between youthful aspirations and the external demands of society and family. Since its first publication in 1972, Goh's novel has moved and delighted generations of readers and was most recently given a new lease of life and adapted into an interactive theatre-dinner production by Marc Nair and AndSoForth in May 2016. |

|

|

Writing Singapore: An Historical Anthology of Singapore Literature This volume, which chronologically surveys literary work from the nineteenth to the twenty-first century, broadens the idea of a national literature with its inclusion of stories and poems from the Malay Annals and the Straits Chinese Magazine, as well as classic and forgotten work by Lee Kok Liang and Kassim Ahmad. With its rich offerings of primary material and criticism, Writing Singapore is an excellent resource for anyone with an interest in Singapore literature. |

|

Remembering the Fall of Singapore February 15, 2017 12:30

On 15 February 1942, Singapore—famously dubbed the “impregnable fortress” and the final British stronghold in Southeast Asia—fell to advancing Japanese troops after a violent campaign that killed 7,000 soldiers on both sides. The Fall of Singapore was, in NUS Press author Ronnie McCrum’s words, “unprecedented in the annals of British history”; despite the portentous warnings of the Second World War erupting in the Pacific region, the surrendering of the ‘Gibraltar of the East’ to the Japanese nevertheless “stunned the British nation and the watching world.”

This week, we commemorate the events of 1942 and the Japanese Occupation with a reading list of NUS Press titles that offer in-depth perspectives of the watershed event and its aftermath:

|

The Men Who Lost Singapore, 1938–1942 This lively new monograph by military historian and retired British Army Officer Ronald McCrum provides an alternative perspective to existing accounts of the Fall of Singapore, all of which engage extensively with military strategy, focusing on the role of the Malaya Command. In contrast, McCrum highlights the vital role played by the civilian colonial administration, which not only failed to prepare the colony adequately for possible invasion, but also created distractions and hostile working relations with the military command. The Men Who Lost Singapore levels a fresh charge against forgotten agents in history, and significantly expands the current body of scholarship about the Asia-Pacific theater of the Second World War. |

|

|

War Memory and the Making of Modern Malaysia and Singapore Having lived through the Japanese Occupation for more than two years, how did the survivors of wartime Malaya remember and reconstruct the trauma associated with the period? How has its memory been shaped by individuals, communities, and states? What’s at stake in the very act of remembrance? Kevin Blackburn and Karl Hack present compelling and richly-illustrated instances where wartime memory and postcolonial exigencies collide, for example, in the debates around the design and construction of the Civilian War Memorial, and the representation of wartime heroism in post-war Malayan cinema.

|

|

|

Asian Labor in the Wartime Japanese Empire During the Japanese invasion of Southeast Asian, thousands of Prisoners-of-War were sent to work on the Thailand–Burma Railway, which—given the dismal conditions of labor—was also dubbed the “Death Railway.” In this volume of essays, edited by Paul Kratoska, an international group of specialists on the Japanese Occupation examine the labor needs and the management of workers throughout the expanding Japanese empire, with a particular view to the experiences of Asian laborers, whose voices are often left out of mainstream narratives. |

|

|

Red Star Over Malaya: Resistance and Social Conflict During and After the Japanese Occupation, 1941–46 In this classic study of the Japanese Occupation and its aftermath, Cheah Boon Kheng performs the groundbreaking task of engaging with vast archives about the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army, which was a communist-led guerrilla resistance movement that formed during the Japanese Occupation and emerged as a significant force of liberation after the war. Now in its fourth edition, Red Star Over Malaya examines the ethnic and racial lines that divided Malaya after the surrender of the Japanese, and continues to shed light on the conditions that shaped Malaysia and Singapore during the turbulent period of decolonization. |

|

|

New Perspectives on the Japanese Occupation of Malaya and Singapore, 1941–45 After their surrender, the Japanese military systematically destroyed war-related documents, severely limiting the range of Japanese-language primary sources about the Occupation in Singapore and Malaya. This volume represents an international effort to gather primary materials from libraries and archives in Britain, Malaysia, Singapore, USA, Australia and India, to illuminate new findings and reconstruct the history of the Japanese Occupation. |

|

|

Guns of February: Ordinary Japanese Soldiers’ Views of the Malayan Campaign and the Fall of Singapore Guns of February, an equal-parts novelistic and scholarly work, highlights the experiences of the Japanese soldiers who fought during the Malayan Campaign. In this book, Henry Frei sensitively examines the prevailing ultra-nationalist ideologies that propelled young Japanese men to risk their lives for their country, and provides much-needed perspective on an imperial war fought on an impossibly alien terrain. |

|

|

Playing for Malaya: A Eurasian Family in the Pacific War Rebecca Kenneison’s Playing for Malaya is a literary and meticulously researched work that vividly describes, in minute detail, the everyday conditions of wartime Malaya. This is a memoir that depicts the experiences of a Eurasian family in Malaya during the Japanese Occupation in all its grim details, revealing in the process the intertwined registers of heroism, tragedy, and endurance. |

|

Five Minutes with Sarah Tiffin February 10, 2017 09:00

When Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles published his landmark book The History of Java  in 1817, ruins were far more than the architectural detritus of a former age. Images of ruins reminded people of the transience of human achievements, and stimulated broader philosophical enquiries into the rise and decline of entire empires. In this edition of Five Minutes with ..., we speak with Sarah Tiffin, author of Southeast Asia in Ruins: Art and Empire in the Early 19th Century, who shares with us how art history has become a useful source to understanding colonialism and why portrayals of the "Other" will continue to pique public imaginations.

in 1817, ruins were far more than the architectural detritus of a former age. Images of ruins reminded people of the transience of human achievements, and stimulated broader philosophical enquiries into the rise and decline of entire empires. In this edition of Five Minutes with ..., we speak with Sarah Tiffin, author of Southeast Asia in Ruins: Art and Empire in the Early 19th Century, who shares with us how art history has become a useful source to understanding colonialism and why portrayals of the "Other" will continue to pique public imaginations.

Colonial art seems undervalued/understudied as a resource that could potentially yield insights into colonial perspectives and preoccupations; why do you think this is so?

Actually, I think a great deal of really interesting and thought provoking work has been done on colonial art, particularly by art historians responding to the ideas initially raised by Edward Said and the ensuing debates surrounding his work. Certainly, their work has had an influence on my own. But I think that in the area I am interested in— the work of British artists in Southeast Asia—there is room for a great deal more scholarship. So often in discussions of British art and empire, the work of British artists in Southeast Asia is overlooked. I think the dominance of India in British imperial thinking and experience has had a big part in this, and it is understandable given the huge quantity of materials that were produced as a result of British rule in India. But there is also a wealth of fascinating material relating to the British in Southeast Asia that could generate some really interesting new scholarship.

A painting by William Daniell titled, ‘The large temple at Brambánan’, from T.S. Raffles, The History of Java, Vol. 2 (London: 1817)

(Image courtesy of The Fryer Library, University of Queensland Library)

Your previous book was about the depiction of Chinese poets by a Japanese artist in the seventeenth century. Have you always been intrigued by the politics of representation behind the portrayals of a culture by others?

Do you know, I hadn’t really thought about that connection before as the starting points for my books were very different. My first book was produced for a small art exhibition that was based around a pair of Japanese screens—it explored the iconography of the screens within the context of 17th century Japan. Southeast Asia in Ruins, on the other hand, grew out of a doctoral dissertation and my studies in Southeast Asian history as well as my interest in British art. What I am particularly interested in is socio-political context, in how art reflects the society in which it is created and at the same time, it also influences that society.

In Southeast Asia in Ruins, you explore how the British saw the ruined candi as evidence of a cultural, and indeed civilisational, decline of Southeast Asian peoples. Did the British apply this line of thinking to their other colonies, or were such notions particular to the Southeast Asian region?

The linking ruins, or images of ruins, with ideas about cultural decline was an essential part of late 18th and early 19th century ruin appreciation. The remains of the past allowed people to derive a melancholic pleasure from contemplating the transience of even the most grandiose of humankind’s deeds and designs, including the demise of entire empires. For British ruin enthusiasts, the fall of civilisation was most throughly associated with Rome—most famously in Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire—but this thinking was also extended to the remains of past civilisations in other parts of the world. The British response to Southeast Asia’s ruins, then, was not a unique one, but part of a wider expression of ruin sentiment.

A painting by William Daniell titled ‘Prome, from the heights occupied by His Majesty’s 13th Light Infantry’, from James Kershaw, Views in the Burman Empire (London, 1831)

(Image courtesy of The Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection)

What piqued your interest in images of Southeast Asian ruins that were idealised popular colonial British imagination?

When I first looked at Raffles’ The History of Java, I was struck by the beauty of Daniell’s aquatint ruin plates. I was familiar with the images of Indian architecture he and his uncle Thomas had created for the superb Oriental Scenery, but I had not seen his images of the Javanese remains before and I felt they really deserved more attention. Similarly, the engraved vignettes by a number of British printmakers that are scattered throughout Raffles’s text are really lovely and very fascinating, yet I found very little had been published on them, or on the wealth of archaeological drawings now held in the collections of the British Library, the British Museum and the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. It has been something of a labour of love, and I hope it might encourage other people to look at these wonderful collections for their own research projects.

William Daniell, A Javan in the court dress (plate from The History of Java by Thomas Stamford Raffles, London : 1817, vol. 1), coloured antiquint

(Image courtesy of the Fryer Library, University of Queensland Library)

What is your next project? Will you return to the museum/gallery scene?

I am currently working on a study of Southeast Asia in 17th century English poetry, prose, pageantry and drama, looking at how authors responded to the aspirations and experiences of English merchants then active in the region, and the changing political and economic imperatives at home and abroad. I’m keen to keep working on this project over the next couple of years, but apart from that, I’m not sure what the future holds!

Sarah Tiffin

(Image provided by Dr Tiffin)

Five Minutes with Ross King February 3, 2017 09:00

Memories, while often thought to be intimate personal recollections, can be

interpreted through a collective lens, where memories and experiences of individuals are weaved together to form collective memories that influence the larger community. In his latest book, Heritage and Identity in Contemporary Thailand: Memory, Place and Power, Ross King situates the notions of social memory, place and power to make sense of the production of Thai heritage and the identity of the Thai people.

In this edition of Five Minutes with, we speak with Prof King to discuss how memories and sites of memories (be it grand locations or everyday settings) contribute to and shape a country’s heritage, and whether the recent passing of the revered King Bhumibol will further polarise Thai society.

What made you decide to delve into the world of contemporary Thailand again, given that your previous book, Reading Bangkok, was also focused on the country?

Heritage and Identity in Contemporary Thailand, quite simply, emerged from my teaching in Thailand. Thai research students, in my experience, tend to be assiduous in the pursuit of good data but there is generally an inhibiting difficulty in bringing sharp, critical thinking to bear of the real issues to which those data might relate. Over the years I have supervised some 32 Thai PhD students; some have produced excellent work but it has not been internationally publishable because of the lack of self-reflection and the failure of critical thinking. My aim in Heritage and Identity was therefore to show how theoretically informed, critical thought might be mobilized to throw light on the phenomena of Thai heritage and identity.

Bangkok, Thailand

(Image credit: Milei.vencel/ Wikimedia Commons)

What was the process of writing Heritage and Identity in Contemporary Thailand like?

It is based on 12 PhD theses and on subsequent work of those scholars. On the basis of my reading of that work I would write a chapter—an essay—that could address the book’s theme of the intersections of memory, place and power. There would then be various interchanges of ideas and drafts between myself and the 12 co-authors until I could get the manuscript to a coherent text. It was a difficult book to write because it was neither one thing nor the other—neither a consistent, single-authored book written to a tight intellectual agenda, nor an edited collection from separate, different authors. Despite the difficulties, I strongly believe that it is a powerful way to bring Southeast Asian scholars to publication, also to bring critical reflection to the work of such scholars.

In this book, there is a large focus on spaces and landscapes in Thailand, such as temples and palaces, as sites of memories. What about these places drew you to explore further into their historical background?

Heritage is always linked to memory—it is what we remember and which thereby defines who we are. And yes, I am certainly interested in the grand sites of memory such as temples and palaces; far more, however, my interest is in the ordinary ‘environments of memory’—the home, the street, the village and the memories that attach to them, for these are the real wellsprings of identity, also of creativity. Further, they are the real heritage of a people.

The book is structured in such a way that its first half dwells on the present memories that attach to ancient places: temples, palaces, remnants of past ages—to the things that might define some officially sanctioned idea of ‘the Nation’; in the second half, it moves on to memories that resonate through everyday life—a canal (khlong), a small street (soi), village, local customs, the home, family.

Fishing Village in Narathiwat

(Image credit: preetamrai/ Wikimedia Commons)

With regards to the recent passing of the revered King Bhumibol, how would the notions of memories and identities of the Thai people relate to the social cohesion of the country? Do you think his passing would deepen the polarization of the Thai community?

Thailand’s is not a unitary culture. Rather, it is an assemblage of diverse ethnicities and cultures. There is generally some sense of harmony, except in relations between central Thailand (mostly Bangkok) and the Northeast (Isan). There is a profoundly cultural base to the division—the people of Isan are, mostly, not Thai but Lao; there are language differences. The rift has stretched over centuries with its origins in ancient conflicts but, even more, in exploitation and brutality leveled by Bangkok against Isan, notably since the 1930s. Hence the Red Shirts and the Yellow Shirts of the present era. King Bhumibol, though controversial especially in his relationships with Thailand’s military coups, had since the 1950s expressed concerns for the depressed conditions of the Isan region. It is notable that, with King Bhumibol’s failing health in recent decades, his previous conciliatory role also failed. Simply, the new King will not be able to replicate his father’s role as the great conciliator. Polarisation will proceed apace.

Portrait painting of King Bhumibol Adulyadej

(Image credit: Government of Thailand/ Wikimedia Commons)

You mentioned in your book that Thai heritage is sustained by the “preservation of deprivation”, maintaining the entrenched inequalities amongst the Thai people. What are your thoughts on how the Thais can bridge this deep divide in their society? Is there any possibility at all?

At one level, it is heritage tourism that is thus sustained. At a deeper level, the book invokes dependency theory to demonstrate how dependency—exploitation—works at a diversity of scales throughout the society. Most seriously it underlies that rift between a Bangkok elite (royalist, middle-class, military) and a repressed Isan. So, what can be done about this? The starting point has to be an understanding of and respect for different memories and experiences—Bangkok must come to understand the tragic history and present condition of Isan, also to understand Bangkok’s continuing role in that tragedy.

Will your next research project be revisiting Thailand or has a new subject matter piqued your interest?

I have a book on Seoul to be published later this year from Hawai‘i University Press. More to the present point, I have completed a book (not yet in press) titled The Tragedy of Isan. Its argument is that the tragedy is one of mis-interpretation: the long history of the rift and its causes has been suppressed, it is not to be remembered. (Even the National Museum in Bangkok virtually ignores Isan, despite its being one-third of the country.) Instead, the rift will be explained by the elites simply as Northeasterner inferiority—“water buffaloes”, they will be labeled—while Isan perspectives will perceive the elites as forever anti-democratic. It is yet again a problem of suppressed memory, and the interpretative task—therefore the task of The Tragedy of Isan—is to strip away suppressed memory. To expose tragic history. In a more positive sense, The Tragedy of Isan is not only to interpret the tragedy and its roots, but also to celebrate the real glory of the culture of Isan and to assert that, in the richness of that heritage, are the tools of reconciliation.

Soft Launch of Southeast of Now at the National Museum of Singapore January 26, 2017 09:00

In conjunction with the Singapore Biennale 2016 Symposium, NUS Press’s newest journal dedicated to art history in the region—Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia—was launched at the National Museum of Singapore’s Gallery Theatre last Sunday (22 January).

(Image credit: Pallavi Narayan)

A panel that included renowned art historians John Clark, Patrick D. Flores and T.K. Sabapathy, NUS Press Director Peter Schoppert, as well as two members of the Southeast of Now editorial collective Simon Soon and Yvonne Low, discussed the significance of producing an academic journal dedicated to contemporary art in the region.

Left to right: Yvonne Low, Simon Soon, T.K. Sabapathy, John Clark, Patrick D. Flores

and Peter Schoppert

(Image credit: Sebastian Song)

John Clark, Emeritus Professor in the Department of Art History at the University of Sydney, opened the session with remarks about the role of journals in forming and sustaining epistemic communities. He spoke on Southeast of Now’s potential to engage “laterally” with other clusters of research within the general field of art history and contemporary arts scholarship, and praised the “chutzpah of young art historians in the field,” citing this as evidence of a thriving community of researchers.

(Image credit: Sebastian Song)

Thereafter, T.K. Sabapathy, a leading authority on art history in Singapore and Malaysia, considered the role of publishers and university presses in fostering an environment conducive to research: “NUS Press,” he rejoined half-jokingly, “has woken up.”

Patrick D. Flores, Curator of the Vargas Museum, Manila, and a professor with the Department of Art Studies at the University of the Philippines, suggested that the journal represents a new development in the professionalization of arts research. He added that the journal also provides young arts researchers invaluable opportunities for acknowledging the “different system of knowledge-making in the region.”

(Image credit: Sebastian Song)

Peter Schoppert elaborated on the series of decisions that led to NUS Press’s acquisition of the journal. According to him, the editorial collective’s energy levels, commitment and openness were “impressive,” and, interestingly, their proposals were also accompanied by “rumours” of their ambition and ability spread by their teachers, supervisors and mentors. To end the panel, he quoted extensively from an interview—included in the first issue of the journal—with Stanley J. O’Connor, on the idea that in the face of global upheaval and changes in the production and practice of art, “nothing can be more important than the decentering of the art world,” a process which is “by no means automatic.”

(Image credit: Sebastian Song)

Southeast of Now will be published twice a year (March and October). Register with Project MUSE to enjoy free previews of Vol. 1, No. 1 (March 2017) and Vol. 2, No. 2 (October 2017). For editorial enquiries, contact the editors at southeastofnow@gmail.com. Click here to find out more subscription rates and to subscribe to the journal.

January-June 2017 Highlights January 13, 2017 11:00

We're pleased to announce that our full January-June 2017 catalogue is now available for browsing and downloading. The following are some key titles to look out for:

POLITICS

|

|

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) turns 50 this year, making The ASEAN Miracle: The Catalyst for Peace a timely tribute to the history (and future) of the regional body. Written by Kishore Mahbubani, Dean of the Lee Kyan Yew School of Public Policy, and Jeffrey Sng, the book highlight the strengths of the ASEAN model of international cooperation, and in the words of Amitav Acharya, the book is a “a powerful and passionate account of how, against all odds, ASEAN transformed the region.”

Turning closer to Singapore’s shores, Chua Beng Huat examines the rejection of Western-style liberalism and continued hegemony of the People’s Action Party in his thought-provoking book, Liberalism Disavowed: Communitarianism and State Capitalism in Singapore. Chua analyses the areas in public policies that are foundational to the political, economic and social stability of Singapore, making his book a valuable read for readers who are interested in Singapore's political economy and public affairs. |

HISTORY

|

|

While many have lamented that countless books have already been written on the Fall of Singapore (which is commemorated on February 15, 1942), Ronald McCrum’s The Men Who Lost Singapore, 1938—1942 will be a valuable addition to the literature of the Japanese Occupation and Pacific War. Professor Greg Kennedy has commended the book as “a must-read for anyone wishing to understand why Singapore's fall occurred in the manner it did."

Fast-forwarding readers to the 1960s and 1970s, Daniel Chua focuses on Singapore’s relations with the United States under Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon in US-Singapore Relations, 1965-1975: Strategic Non-alignment in the Cold War. Chua argues that against the backdrop of the US’s policy of containment at the height of the Cold War, the superpower took a great interest in Singapore’s nation-building and was integral to Singapore’s development. This counters the well-trodden narrative of Singapore's growth from “Third World to First” merely because of good governance. |

CONTEMPORARY ART HISTORY

|

|

David Teh’s Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary examines the tension between the global and the local in Thai contemporary art. The first serious study of Thai contemporary art since 1992, Teh analyses the work of artists who straddle the local and the global, against the backdrop of sustained political and economic turmoil.

Last but not least, Yvonne Spielmann’s Contemporary Indonesian Art: Artists, Art Spaces, and Collectors is a comprehensive overview of artists, curators, institutions, and collectors in the Indonesian contemporary art scene. Spielmann demonstrates how contemporary art breaks from colonial and post-colonial power structures, and grapples with issues of identity and nation-building in Indonesia.

|

We will also be launching a new art history journal Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia this year. It will be published twice a year (March and October) and you can enjoy free previews of the inaugural issue (Vol. 1, No. 1 [March 2017]) and Vol. 1, No. 2 (October 2017) by registering with Project MUSE.

Subsequent issues from Vol. 2, No. 1 (March 2018) will be available upon subscription. Subscription form is availabe here.

Events to Start The New Year January 6, 2017 11:30

Professor Kenneth Dean and Dr Hue Guan Thye will be launching their magnum opus Chinese Epigraphy in Singapore, 1819-1911 at the POD at the National Library on 10 January (Tuesday), 6.30-9pm. The event is free to attend but registration is required via Eventbrite.

In this two-volume set, Professor Dean and Dr Hue have painstakingly recorded and translated over 1,300 epigraphic records of 62 Chinese temples, native place associations, clan and guild halls. These materials, dating from 1819 to 1911, include temple plaques, couplets, stone inscriptions, stone and bronze censers, and other inscribed objects found in these institutions. Available in Chinese and English, this reference set opens a window into the world of Chinese communities in Singapore.

Chinese Epigraphy in Singapore, 1819-1911 is available at S$220 for the whole month of January (original retail price: S$245). Enter the code ChineseEpigraphy during checkout to enjoy free delivery in Singapore.

On a more art-historical note, we will be soft-launching a new art history journal, Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, at the National Museum of Singapore Gallery Theatre on 22 January (Sunday), 6.30-7.30pm. It will be held on the second day of the Singapore Biennale Symposium (21-22 January).

The launch is free (and you can attend it without a Symposium ticket) but registration via Eventbrite is required.

You can purchase tickets for the weekend-long symposium via Sistic: http://www.sistic.com.sg/events/csb0117 (S$50 for a 1-day pass and S$90 for a 2-day pass).

Cover photo taken by Michael James Colbourne, 'David Medalla in an impromptu shot before rice-planters, with Sonia Monillas, Rizal province, Philippines, 1959.’ (Collection of David Medalla, 'another vacant space', Berlin).

Southeast of Now presents a necessarily diverse range of perspectives not only on the contemporary and modern art of Southeast Asia, but indeed of the region itself: its borders, its identity, its efficacy and its limitations as a geographical marker and a conceptual category. The first issue will be officially published in March 2017 and it will be published twice a year (March and October).

Register with Project MUSE to enjoy free previews of Vol. 1, No. 1 (March 2017) and Vol. 1, No. 2 (October 2017). Subsequent issues (print and digital) will be available upon subscription.

For editorial enquiries, contact the editors at southeastofnow@gmail.com.

For subscription enquiries, contact the National University of Singapore Press at nuspressbooks@nus.edu.sg.

NUS Press Highlights of 2016 December 27, 2016 10:30

While 2016 has proven to be a rather bleak and tumultuous year, we are proud to have published some books that will continue to have much bearing in the new year ahead.

ENVIRONMENT

All eyes will continue to be on Indonesia’s Peatland Restoration Agency as it implements plans of restoring peatland to prevent haze crises (like that of 2015) from engulfing the region again.

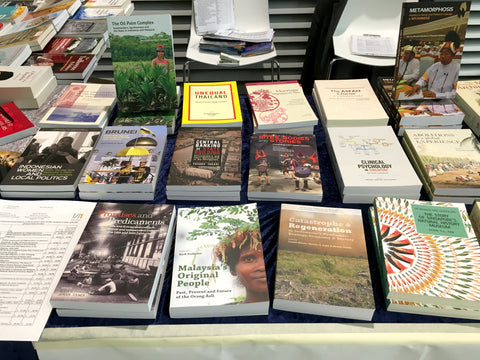

Two NUS Press books, Catastrophe and Regeneration in Indonesia’s Peatlands (edited by Kosuke Mizuno, Motoko S. Fujita and Shuichi Kawai) and The Oil Palm Complex (edited by Rob Cramb and John McCarthy) touched on some agricultural and labour challenges that Malaysia and Indonesia are facing within the oil palm industry and peatland agriculture. In his review of both books in The Jakarta Post, James Erbaugh commented that both titles “provide scholarship that elucidates the complexities of oil palm production, and the challenges presented by peatland agriculture as well as peatland restoration.”

POLITICS

Indonesia’s gubernatorial election is set to take place in February 2017 and Edward Aspinall’s and Mada Sukmajati’s edited volume, Electoral Dynamics in Indonesia will be handy for observers as it provides greater insight into the patronage systems and money politics at the grassroots level.

In the field of maritime developments: Tensions in the South China Sea will continue to have much bearing on US-China and China-ASEAN relations in 2017. Ng Chin-keong’s collection of essays, Boundaries and Beyond, provides a novel way of understanding the nature of maritime China, and the undercurrent of social and economic forces that have created new boundaries between China and the rest of the world.

Lastly, in light of the 29th Southeast Asian Games taking place in Kuala Lumpur next year, Stephen Huebner’s Pan-Asian Sports and the Emergence of Modern Asia, 1913-1974 explores the role international sporting competitions had in shaping discourses of nationalism and development across Asian states. As one of the first major studies of the history of sports in Asia, Dr Huebner’s book provides a compelling window into the intersection between sports and politics in the region.

SINGAPORE HISTORY

The history of pre-independence Singapore remained a staple to our publishing programme this year, with Timothy Barnard’s Nature’s Colony shedding much light on the Singapore Botanic Gardens' lively history. Professor Barnard examined the Gardens’ changing role in a developing Singapore—from colonial times under the charge of several colourful Superintendents and Directors, to today, as a World Heritage Site.

On a more personal level, social work pioneer Ann Wee reminisces about her eventful life in Singapore. Her memoir A Tiger Remembers ruminates on the Singaporean family, and presents the reader with a series of charming vignettes from her life that captures the nuanced transformation of Singaporean society over the years. These intimate recollections, all told in exquisite detail and rich with insight, are testament to the vibrant cultural heritage of the nation.

We are also proud to have published Professor Kenneth Dean and Dr Hue Guan Thye's two-volume set, Chinese Epigraphy in Singapore, 1819-1911, which has been described by Claudine Salmon, Director of Research Emeritus at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), Paris to be a "a repository of Singapore cultural and historical heritage." The collation of over 1,300 epigraphic records is a breakthrough in the telling of the Singapore story and according to Prof Dean, "such inscriptions provide snippets of what life was like in 19th and early 20th century Singapore, and capture the diverse cross-section of society at that time."

SOUTHEAST ASIAN ART HISTORY

What importance does art hold in the representation of history?

In the context of the portrayal of Southeast Asia by its colonial masters, Sarah Tiffin’s Southeast Asia in Ruins explores how the British justified colonialism through imperial art. Dr Tiffin will be speaking at the National Gallery Singapore on 25 February 2017 about British artists' portrayal of Southeast Asian civilization(s) in ruins in Stamford Raffles' The History of Java, and the role that these artists (and their work) played in Britain’s imperial ambitions in Southeast Asia.

In 2017, photographers and photojournalists will continue to play a vital role in exposing the realities of an increasingly authoritarian Southeast Asia. Zhuang Wubin’s Photography in Southeast Asia will be a useful introduction to the discourse of photographic practices in the region as his survey provides insights into the role images play in shaping Southeast Asian society, culture and politics.

Five Minutes with Brian Bernards November 22, 2016 15:00

In this special edition of our author-interview series, Professor Philip Holden from the National University of Singapore conducted an email interview with Professor Brian Bernards on the occasion of the publication of the Southeast Asian edition of Writing the South Seas: Imagining the Nanyang in Chinese and Southeast Asian Postcolonial Literature. An assistant professor at the University of Southern California, Bernards works in three languages – English, Chinese, and Thai—and his book thus gives a revisionary perspective on the literatures of the region, and indeed the way in which we imagine Southeast Asia itself.

University of Singapore conducted an email interview with Professor Brian Bernards on the occasion of the publication of the Southeast Asian edition of Writing the South Seas: Imagining the Nanyang in Chinese and Southeast Asian Postcolonial Literature. An assistant professor at the University of Southern California, Bernards works in three languages – English, Chinese, and Thai—and his book thus gives a revisionary perspective on the literatures of the region, and indeed the way in which we imagine Southeast Asia itself.

Professor Holden's and Professor Bernards' exchange was first published on singaporepoetry.com. We are pleased to present some excerpts of their lively discussions:

Philip Holden: As someone who has been studying auto/biography, I’m always interested in the life stories of scholars. What drew you to study Chinese and Thai? And what fostered your interest in the literatures of Southeast Asia?

Brian Bernards: When I was 9 years old, a family from Shanghai (a father, mother, and their 2-year-old daughter) moved in with my family at our home in Minneapolis. The father was studying engineering at the University of Minnesota, and the mother, who later went on to study accounting, became our live-in babysitter. On occasion, our two families had meals together, and the boiled dumplings (shui jiao) our sitter cooked became quickly my new favorite dish. Our good friends from Shanghai lived with us for about two years, when the father graduated and found a plush job in Milwaukee. Starting high school about three years later in 1992, I opted to take Mandarin because of my prior exposure to Chinese culture (and cuisine!). I first traveled to mainland China in 1998, where I studied for a year at Sichuan University in Chengdu. My language professor recommended Chengdu because she had done research there, she knew I wanted to tread beyond the typical path of studying in Beijing, Shanghai, or Taipei, and, most importantly, she knew I would like the spicy ma-la food there. Living and attending school in Chengdu certainly opened my eyes, and my taste buds, to new experiences, flavors, and possibilities.

PH: Given your exposure to different disciplines, what are your thoughts on inter-disciplinary studies?

BB: I have always enjoyed literature (especially fiction and poetry), music, and film. As a student and traveler, I felt I could better connect with a place, a culture, a society, and its history through the very personal stories and creative imagination conveyed in fiction and memoirs by authors who were from or who were very familiar with that society. While Southeast Asian studies in the US is largely a social science-oriented field, I was fortunate to take history and anthropology classes as an undergraduate from professors who, rather than assigning dry textbook readings, assigned novels by authors such as Pramoedya Ananta Toer, José Rizal, Duong Thu Huong, Ma Ma Lay, and Kukrit Pramoj, to be read in conjunction with course lectures. I was very inspired by this approach to history and cultural studies, not only because it put the human impact of historical events and social transformations in relatable narratives rather than abstract figures, but also because the micro-histories we encountered in such literary narratives often challenged or even contradicted the standard interpretations and “big picture” perspectives taken for granted in the official histories. I am grateful to my teachers for cultivating the approach that would stick with me as I moved forward into graduate studies.

PH: What was the process of writing Writing the South Seas like?

BB: Writing the South Seas began as a way of combining my interests and background knowledge in modern Chinese literature, Southeast Asian studies, and postcolonial literary theory in an attempt to make a novel contribution, and hopefully a type of critical intervention, in each field. I felt the varying approaches from these different fields could be mutually illuminating in ways that the disciplines had yet to sufficiently consider. Mainly, I sought to bring a Southeast Asia-centered perspective to the study of literatures in Chinese on and from the region. Luckily, I conceived the project at the time that Sinophone studies was emerging and bringing about a sea-change in the modern Chinese literary field. Sinophone studies not only emphasizes cultural networks across national and ethnic boundaries, but also seeks to situate such networks locally in their multilingual milieu. In this sense, my interests in Anglophone literature and Thai-language literature from Southeast Asia, which might have otherwise been seen as irrelevant or marginal to modern Chinese literary studies, could provide an insightful comparative perspective that showcased the cross-lingual interactions and relationships of these Sinophone literary networks. I owe a significant intellectual debt to the pioneering work of Shih Shu-mei in this regard.

PH: The cover of your book will have a particular resonance for many Malaysians and Singaporeans. Could you explain this?

BB: I really have you to thank for this, Prof Holden, as you were the first person to recommend Suchen Christine Lim’s novel Fistful of Colours to me when I began researching Anglophone authors in Singapore. As you know, at the end of the novel, the protagonist returns to Kuala Jelai, her home village in Malaysia, from Singapore, and she becomes moved viewing the large wall murals while waiting for her train at the Tanjong Pagar Railway Station. When I read this passage, I wanted to see the murals myself, though at the time I had no idea they would later provide the source material for the cover of my book.

That was before the station closed. When it was operational, the station, along with the Keretapi Tanah Melayu (KTM) railway tracks, was an important living legacy of the intimate relationship, common colonial history, and shared culture between the two countries. Now that it is closed, it can only serve as a “heritage site” – a relic or a reminder of that past. For a lot of Malaysians and Singaporeans who grew up when the two societies were more integrated, Tanjong Pagar is bound to be a source of nostalgia, especially because it conjures a more rustic landscape and older colonial architecture that contrasts with the image of Singapore as a city of glistening skyscrapers and squeaky-clean air-conditioned malls. I think this nostalgic sentiment regarding the railway station is quite obvious in “Parting,” director Boo Junfeng’s contribution to the omnibus film, 7 Letters: he uses the space of Tanjong Pagar to tell the story of an interethnic romance against the backdrop of racial riots in the 1960s.

Interior of Tanjong Pagar Railway Station, 2010

(Image credit: Jacklee, Wikimedia Commons)

Of the six triptych murals in the station, the one with the commercial maritime focus showing the harbour was the most relevant to my book in its entirety, so I commissioned an image of that mural for the cover. The different types of ocean vessels in the image, from a sampan to a junk to a passenger steamship, really captured the varying modes of maritime crossings and convergences that the Nanyang has historically signified. And it’s beautifully done.

****

NUS Press would like to thank singaporepoetry.com's founding editor, Koh Jee Leong for granting permission to republish these excerpts.

Sayonara, 2016 Singapore Writers Festival November 18, 2016 17:00

With Japan as its country focus, the 19th Singapore Writers Festival came to an end last weekend after ten action-packed days of literary talks, discussions, music, and performances.

NUS Press was proud to have been one of five publishers featured in The Paper Trail, a backroom tour of Singapore publishers led by poet Yong Shu Hoong on November 5. Our director Peter Schoppert addressed a group of about 30 people and gave a quick overview of the history of the university press, and how it came to establish a foothold in the academic publishing scene in Asia.

(Image credit: Caroline Wan, National Arts Council)

(Image credit: Yong Shu Hoong)

Author Yap’s poems and short stories, and Goh Poh Seng’s memoir and novel, If We Dream Too Long, were naturally snapped up by some tour participants.

(Image credit: Caroline Wan, National Arts Council)

On November 6, two of our authors, Lim Cheng Tju, co-author of The University Socialist Club and the Contest for Malaya: Tangled Strands of Modernity, and Mrs Ann Wee, author of A Tiger Remembers: The Way We Were in Singapore, appeared on a panel alongside Nilanjana Sengupta at the Asian Civilisations Museum to share how everyday experiences, lesser-known stories, and oral histories are crucial for a better understanding of Singapore's past.

(From left to right) Nilanjana Sengupta, Lim Cheng Tju and Ann Wee

(Image credit: Chye Shu Wen).

Last but not least, we caught the matinee performance of The Finger Players’ love-letter to Singapore’s literary history, Between the Lines: Rant and Rave II. It was a delight to watch Serene Chen and Jean Ng act out key literary milestones in the development of Singapore’s cultural landscape. We were thrilled to have had some of our publications and authors (Edwin Thumboo, Arthur Yap and Goh Poh Seng to name just a few) featured in this play.

(Image credit: Chye Shu Wen)

At the end of the play, the stage became a pop-up shop for 30 minutes and it was heartening to see audience members stream down to the stage to browse through and purchase the books that were featured in the play.

(Image credit: Chye Shu Wen)

We look forward to the 20th edition of the Singapore Writers Festival, which is set to take place from 2–13 November 2017.

NUS Press at the 2016 Singapore Writers Festival November 4, 2016 11:00

NUS Press is pleased to be participating in this year's Singapore Writers Festival (SWF)! Themed "Sayang," the festival will feature close to 320 writers, speakers and performers between November 4–13.

To celebrate, we are offering special prices for this selection of titles!

We will also be featured in these main events:

Singapore Untold | 6 Nov, 1–2pm |

Asian Civilisations Museum (Ngee Ann Auditorium)

Our authors, Ann Wee, a pioneer of social work education in Singapore and author of A Tiger Remembers: The Way We Were in Singapore, and Lim Cheng Tju, co-author of The University Socialist Club and the Contest for Malaya: Tangled Strands of Modernity, will be appear in this panel alongside Nilanjana Sengupta to discuss why they have written stories that are often not found in Singapore history textbooks. They will also talk about their experience of uncovering and writing these stories.

You can attend this event with a SWF Festival Pass (S$20), which is available via SISTIC.

Ann Wee (left) and Lim Cheng Tju (right) (Image sources: Singapore Writers Festival).

Between the Lines: Rant & Rave II | 4–6 Nov, various times |

School of the Arts (SOTA) Studio Theatre

Simultaneously a crash course in, and a love letter to SingLit, Between The Lines: Rant & Rave II will take you on an odyssey of the evolution of the English-language literature scene in Singapore through the decades. Actors Serene Chen and Jean Ng as they take on the roles of real-life poets, novelists, publishers and many more in this loving tribute to the written word.

NUS Press is pleased that a number of books and authors we have published (from Edwin Thumboo's 1973 book, Seven Poets: Singapore and Malaysia, to Arthur Yap's Collected Poems) will be featured in this performance!

Between the Lines was commissioned by SWF and is presented by The Finger Players. Tickets (S$35) are available via SISTIC.

Serene Chen and Jean Ng rehearsing for "Between the Lines" (Image courtesy of The National Arts Council).

The Paper Trail: A Backroom Tour of Singapore Publishers (SOLD OUT) |

5 Nov, 9am–1pm | Various locations

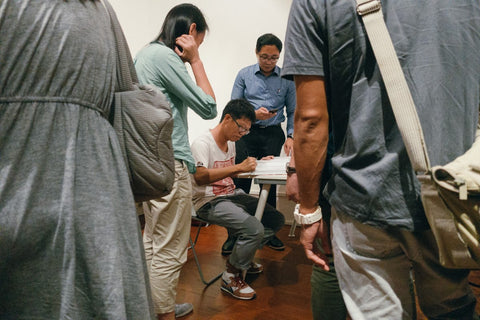

Launch of "Nature's Colony" at the Singapore Botanic Gardens October 21, 2016 11:00

Timothy Barnard launched his latest book, Nature’s Colony: Empire, Nation and Environment in the Singapore Botanic Gardens, at the Singapore Botanic Gardens on October 14, as part of the Gardens' regular speaker series.

(Photos courtesy of Sebastian Song)

Professor Barnard centred his talk around the history of the Gardens and its broader impact beyond its bounadries in environmental, political, and

social terms.

(Photos courtesy of Sebastian Song)

Professor Barnard explained that the botanic gardens was established as a private park between 1869 and 1874. By the early 1870s, the British realised that it had the potential of becoming a key colonial institution because imperial botany was seen as a tool that could strengthen empire (i.e. rubber seeds could be harvested in Singapore and Malaya, which could then be traded as a commodity).

The ever-changing position of the Singapore Botanic Gardens in society and politics over time has also often been overlooked: Professor Barnard emphasised the Gardens' precarious position as a colonial institution in a decolonialising society in a post-Merdeka era.

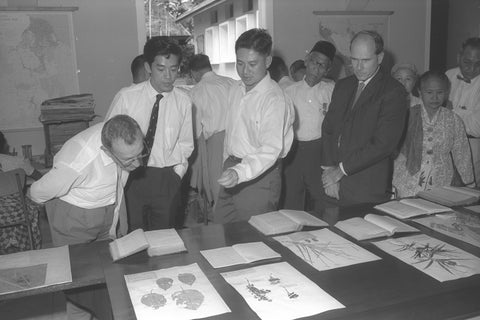

Humphrey Burkill, Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens from 1957 to 1969, leading a tour of government officials at the opening of the “renovated” herbarium in October 1964 (Source: Ministry of Information and Arts Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore).

One of the highights of the talk was a segment on Henry Ridley, the Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens between 1888 and 1912. Ridley was seen as “mad” by many of his contemporaries within the colonial government in Singapore due to his quirks and views of how the Singapore Botanic Gardens should be developed.

Ridley accomplished a lot during his tenure as director—from overseeing the set up of a short-lived zoo (1875-1905), to the establishing an Economic Garden within the park. Ridley also had the foresight to see that planting oil palm would have economic advantages for the region.

Henry Ridley with a small panther (Image reproduced with the kind permission of the Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew).

The talk was followed by a lively question and answer session that was moderated by the Group Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens, Dr Nigel Taylor.

(Photo courtesy of Sebastian Song)

At the end of the talk, many queued up patiently for Barnard to sign their copies of Nature’s Colony.

(Photos courtesy of Sebastian Song)

We would like to thank the Singapore Botanic Gardens for hosting the launch. If you would like to hear snippets of what Barnard said that day, you can check out his interview with talkshow host, Michelle Martin, on 93.8 Live’s Culture Café here, where he discussed his book and the history of the Gardens.

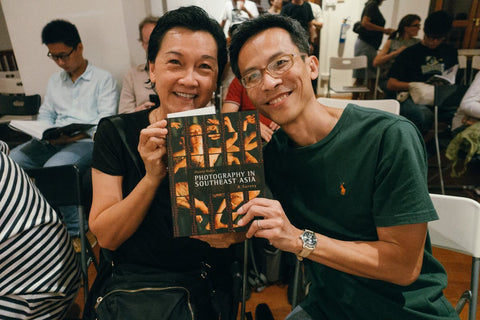

Launch of "Photography in Southeast Asia" in Singapore October 18, 2016 17:00

Zhuang Wubin's Photography in Southeast Asia: A Survey was launched at Objectifs Centre for Photography and Film on October 13, 2016. The launch featured a dialogue between Zhuang and famed street photographer, Chia Aik Beng, followed by a lively question and answer session.

(Photo courtesy of Kevin Lee)

Zhuang and Chia discussed the influence and impact social media has had on photography. When asked by Zhuang about the advantages and disadvantages of using Instagram as a platform for showcasing work, Chia said, "Instagram is a social media platform; it is not a photo gallery or website. If I'm on a project, I will share some images [on my Instagram account], to tease people and then direct them to my website. This is how I distribute information."

For a detailed transcript of what was discussed during the book launch, you can read Invisible Photographer Asia's coverage of it here. We are grateful to Objectifs for sponsoring the venue for this book launch, and to Kevin Lee for being the official photographer of the event.

NUS Press Book Launches in October 2016 October 7, 2016 15:00

October is looking up to be a very busy but exciting month for us with three book launches taking place in Singapore!

|

BOOK LAUNCH & DIALOGUE

|

|

AUTHOR TALK & BOOK LAUNCH

|

|

BOOK LAUNCH

|

International Translation Day: Five Minutes with Frank Palmos September 30, 2016 09:20

Why does translation matter?

The rise of works being translated into English in recent years seems to have made that question a rhetorical one, and it is clear that English readers are becoming more interested in literary and non-fiction works that have been written in different languages.

The rousing reception towards translated non-fiction work, like Thomas Piketty’s bestseller, Capital in the 21st Century (translated by Arthur Goldhammer), and literary works like this year’s Man Booker International winner, Han Kang’s The Vegetarian (translated by Deborah Smith), shows that translators are set to take on a more major role in the world of publishing.

To celebrate International Translation Day, which falls on 30 September every  year, we caught up with Frank Palmos, the acclaimed journalist, historian, and translator of works such as Bao Ninh’s award-winning The Sorrow of War, and more recently, Revolution in the City of Heroes, a first-hand account of Indonesian nationalists’ efforts to gain independence from the Dutch in Surabaya in 1945. Here, Dr Palmos shares his experience of translating and why translations are important for the preservation of memory and history.

year, we caught up with Frank Palmos, the acclaimed journalist, historian, and translator of works such as Bao Ninh’s award-winning The Sorrow of War, and more recently, Revolution in the City of Heroes, a first-hand account of Indonesian nationalists’ efforts to gain independence from the Dutch in Surabaya in 1945. Here, Dr Palmos shares his experience of translating and why translations are important for the preservation of memory and history.

Translators have been said to be literary activists, given that they play such a strong role in facilitating the travel of stories across borders of language. Can you tell us more about your experience in translating fiction (The Sorrow of War) and non-fiction (Revolution in the City of Heroes)?

The “borders” my languages had to cross borders were very local indeed. I was born in a tiny timber town in Central Victoria and schooled in a tiny one-roomed, six-class school of rarely more than 35 pupils, which was rated a hardship post for teachers, resulting in a rapid turnover of teachers and accents, from harsh Australian to middle-England or Northern Ireland.

My Irish-descended Australian-born mother, who spoke faultless, wonderfully clear English, married a Greek born man who never did master English (so he spoke with a Greek accent), and I learnt to both imitate and understand at a very early age. My neighbours were Scot-born, tough country folk whose harsh accents were also a good training for me. By the time I was ten years of age, I could entertain my classmates and certain adults by imitating all these accents.

The two books that you have translated deal with very heavy topics such as ideological battles and wars of independence. What draws you to translate stories like this?

I won a United Nations (UN) sponsored Fellowship in Djakarta (as it was known then) in 1961, administered by the Indonesian Foreign Office. Part of the reward was being able to live with Indonesian families of my choosing, which helped me learn about Indonesian people and their habits from early morning until late at night. I soon discovered almost every Indonesian spoke a regional language and Bahasa Indonesia, the national language. Hence I began to speak and mentally translate Sundanese as well as Indonesian when with my first family in Bandung.

I enjoyed listening to President Sukarno speak so much that I studied hard to attain a level that gave me confidence to request a position as an unofficial translator of President Sukarno’s annual August 17 Independence Day speeches. I was given the requisite passes to the Merdeka Palace and permission to hook up my headphones to an old National radio set.

President Sukarno (Source: Wikimedia Commons).

I was placed about 25 metres behind the president, facing away from him and towards the large assembly of diplomats and foreign press. I gave a passable simultaneous translation of his 1961 Independence Day speech. I hardly

remembered a word of it, but others said I got almost one half of the speech correct, without missing any important dot points. Sukarno often repeated his main points, which helped. Years later, my UN interpreter colleagues comforted me by saying they, too, hardly remembered any of their simultaneous translations. The brain switches itself into automatic translation gear.

I found that I liked doing that work and particularly enjoyed answering the telephone in my hosts’ Jakarta homes, successfully conversing without the callers knowing I was a foreigner, although once, Deputy Prime Minister Johannes Leimena called with a message for my host and upon ending the call, asked if my parents were Dutch. “I think I hear a little Dutch accent,” he said.

How has your background in journalism helped in translating?

The first reason I was comfortable writing the English Version of Bao Ninh’s book was that my original translator of my 1990 book, Ridding the Devils, Madame Hao, was a very reliable technical translator. The second reason was that I did not regard The Sorrow of War as fiction, nor frankly did Bao Ninh, although he had to clothe his stories in certain make belief vignettes. Ridding the Devils was non-fiction, so I wrote Sorrow of War using the same depth of knowledge gained on 33 land, sea and air missions, as a Vietnam War correspondent.

Usually, foreign correspondents do not learn the languages of the countries they report. It is one of the great failings that still exists throughout the western world today, where publishers rarely place correspondents abroad for more than three or four years and do not interest themselves in funding language training or cultural adaptation. I funded my own fare to Indonesia in the days when a flight to Djakarta was the equivalent to AUD $5,000 return today, on a BOAC Comet.

My interest in Indonesia began in 1961 and will continue until I die. I find no difficulty in retaining my love for Australia, Greece, France, and Singapore, for that matter, where I lived in the dramatic years during the formation (and partial break-up) of Malaysia. But as an historian, I find it my duty to repay the hospitality and friendship of the Indonesian people.

In the Sukarno years (1950–1965) research into the foundations of the Republic were not welcomed because the President felt that “nation building” was more important, and by nation building he meant that to keep the peace he did not wish to place greater credit on one ethnic group over another. The role of Surabaya and East Javanese was not accentuated, yet that was where the Republic finally won a small piece of territory for the fledgling Republic at a time when independence seemed an eventuality many years off.

I have used my research and translation skills and my past friendships with Indonesian leaders, many of whom were founders of the Republic, to write the complete history of the founding of the Republic in 1945. It was printed last week in Bahasa Indonesia, titled Surabaya 1945: Sakral Tanahku (Surabaya 1945: Sacred Territory).

Surabaya after the uprisings on 31 October 1945 (Source: Universities Kristen Petra; this photo is part of the collections at the Imperial War Museum).

However, Revolution in the City of Heroes—the Suhario Padmodiwiryo (alias "Hario Kecik") diary that is known as Student Soldiers in its original form in Bahasa Indonesia—is an important part of Indonesia’s history and of that Surabaya story. Unless I had worked with the author (General Suhario) until his death in December 2014, that history would have been lost. In years to come this generation of modern Indonesians will look back and be thankful that works like Kecik’s are in their National Archives.

Five Minutes with Nicholas Herriman September 23, 2016 15:00

If you thought witch-hunts were a thing of the 17th cenutry, think again.

In 1998, around 100 people were killed for being sorcerers in Banyuwangi, Indonesia. This figure far outnumbers the number of people who were executed during the Salem witch trials of 1692–1693, where 200 were put on trial and 20 were executed.

Nicholas Herriman, a senior lectuerer in Anthropology at La Trobe

University, set out to find out why the killings happened as part of research for his PhD thesis between 2000-2002. His findings and arguments about the Banyuwangi incident are presented in his latest book, Witch-Hunt and Conspiracy: The ‘Ninja Case’ in East Java. We caught up with Dr Herriman to talk about witch-hunts, why anthropology is an important discipline in the study of culture and society, and his interest in podcasts (and making them).

Were the sorcerer killings in Banyuwangi the first cases to pique your interest in witchcraft and magic?

Honestly, yes! Prior to learning about the killings, my interest in Indonesia had focused on cultural performance and literature. I first heard about the sorcerer killings in 1998. The killings troubled by me. I wondered, “How could there be a witch-hunt in modern times?” I also thought, “Who was behind the killings? Who benefitted from the killings?”

These questions, it turned out, were naïve and misplaced. But I asked myself these kinds of questions. Arriving in the field in 2000, I still assumed that the witch-hunt had nothing to do with magic, but was rather tied up with national political interests. While doing fieldwork (2000–2002), I began to realise that witchcraft and magic were crucial to understanding the killings. That was the first time my interest was piqued.

In Southeast Asia today, is the belief and practice of black magic and sorcery still very common?

As far as I can tell, belief in and practice of black magic and sorcery are very common. We could qualify that statement, as academics are wont to do, by questioning what we mean by “belief”, “practice”, “magic”, and “sorcery”. Nevertheless, studies from different parts of the region report on widespread suspicions. People suspect that their neighbour, colleague, rival, or whoever it might be draws on extraordinary or unseen powers for immoral ends. The people suspected are from the heights of power to the poorest and disenfranchised.

What were the challenges you faced during your field work in Banyuwangi when you undertook the task of conducting over 100 interviews for ethnographic research?

Professionally, the fieldwork was easy. People readily admitted to killing suspected sorcerers. Indeed, in some cases, they boasted and overstated their roles! By contrast, I struggled, personally. Initially I was horrified—I had to deal with ill health and exhaustion. I kept going primarily because I thought it was crucial to get an accurate historical record this massacre; especially as press and academic reports were so misleading. I wrote Witch-hunt and Conspiracy with this objective in mind.

This woman believed she had been ensorcelled. Her protruding stomach is visible from the profile. Dr Herriman is in the background. (Photo courtesy of L. Indrawati)

What are your thoughts about interdisciplinary studies? Upon reading your book, one can see that the historical and political contexts are very important to explaining how local dynamics or reactions to a situation came about (I.e., In your book, the context of 1998 being a period of Reformasi was very important in explaining how locals were reacting to political and social change after the fall of the Suharto government).

My feeling is that context is crucial in all studies of culture and society. Nevertheless, when I compare the anthropological approach with the interdisciplinary approach, I can discern differences in how to treat this context. Based on my fieldwork, the first book I wrote is called The Entangled State. I wrote this as an anthropologist. I was concerned with how the official treatment of the “problem of sorcery” in Banyuwangi could relate to anthropological theories about the state. I contended that the state was entangled in local communities. Because of this, I argued, senior bureaucrats are hamstrung in trying to contain the “problem of sorcery”.