News

Follow NUS Press on

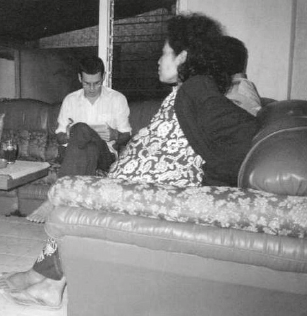

Remembering Ann Wee December 12, 2019 18:31

We received the news on December 11th that Ann Wee had passed away that day, aged 93. She was last in the office a few weeks earlier to chat about the sequel she was writing to her 2017 memoir with NUS Press, A Tiger Remembers.

Ann was a cheerful and inspiring presence to all of us at the press. More than being a delightful author to work with, and a frequent attendee of our book launches and events, she was an inspiring model of how to live: seeking to cross cultural borders, moving out of her comfort zone, first observing carefully, then seeking to help, rarely judging, always ready to learn. An Older Person With Attitude, she was the very opposite of preachy:

“When some elderly person claims that, by virtue of his being old he also has wisdom to share, run for cover. He is almost guaranteed to be on the verge of bombarding you with his opinions, which by virtue of his immodest claim, you can be almost certain will be a collection of personal biases and prejudice.

”I have said ‘he’, and it is true that I have met this more often in older men. But what of the occasional older woman with this self delusion? Watch out! She has the Queen Bee Syndrome, and the rest of us in that hive had better stop buzzing around and listen....”

Ann had a presence for sure, but she was was never Queen Bee.

When asked about her memoir, I am apt to say that it is the single best book I know for appreciating Singapore’s transformation over the last 60 years. That might be quite a claim for such a slim and personal volume. Ann certainly knew the statistics and policy narratives of Singapore’s astounding economic development, of its journey from Third World to First. But the stories she tells in her book are stories of people, within their families and social circles, among their colleagues, sometimes in life crisis, sometimes just dealing with the complications of life, work, family or bureaucracy. Hearing these stories is to understand what better education, better health care, better living conditions, expanded opportunity and social change really mean. It yields a far more powerful insight than the one that comes from marveling over Singapore’s changing skyline, impressive as it is.

The single passage of A Tiger Remembers I most admire is Ann’s dedication. Here she does make a judgement, she lets us know what is important to her. You might be tempted to interpret this as a conservative sentiment, even traditional: yet notice how it is tempered with a deep and seemingly so natural understanding of diversity and of difference.

“To the family in all its 101 different shapes and sizes. With its capacity to cope which ranges from truly marvellous to distinctly tatty: still, in one form or another, the best place for most of us to be.”

We will miss Ann!

Five Minutes with Samuel Ling Wei Chan May 15, 2019 09:42

I n April this year, Dr Samuel Ling Wei Chan published "Aristocracy of Armed Talent, The Military Elite in Singapore". It explores the Singapore Armed Forces by a comprehensive and in-depth examination of its elite leadership: the 170 men (and a very few women) who served or serve as flag officers, that is generals or admirals. How did Singapore build a culture of leadership for its armed forces? What role did the SAF Scholars scheme, introduced in 1971, play in forming this culture?For this edition of Five Minutes With... we turned to noted military expert and journalist David Boey, who conducted this interview and first ran it on his excellent blog on Singapore military matters, Senang Diri. Thanks to David for the interview and for giving us permission to run it on the website.

n April this year, Dr Samuel Ling Wei Chan published "Aristocracy of Armed Talent, The Military Elite in Singapore". It explores the Singapore Armed Forces by a comprehensive and in-depth examination of its elite leadership: the 170 men (and a very few women) who served or serve as flag officers, that is generals or admirals. How did Singapore build a culture of leadership for its armed forces? What role did the SAF Scholars scheme, introduced in 1971, play in forming this culture?For this edition of Five Minutes With... we turned to noted military expert and journalist David Boey, who conducted this interview and first ran it on his excellent blog on Singapore military matters, Senang Diri. Thanks to David for the interview and for giving us permission to run it on the website.

How long did it take you to write the book?

The book is a revised and updated edition of my PhD thesis. I started my studies in March 2011 but by February 2012 it was apparent that my initial topic (on military education in Australia and the US) was not tenable.

What made you press on with research on the SAF despite initial hurdles?

It was a challenge to complete a puzzle and I was focused on the task at hand. The topic is interesting to me, both in academic and general terms.

What was the most challenging aspect of the research for this book?

The most challenging aspects were access to information in terms of open source material and interviews for the specific questions that I had in mind.

How did you go about resolving the challenge(s)?

The 28 interviews were great and a blessing in terms of being able to get the work done.

Which chapter did you enjoy researching/writing most?

I must say I enjoyed them all due to the variation, focus, and information in each of the chapters.

What are the takeaways you hope the reader will glean from the book?

To appreciate the SAF in its entirety, both the good, the quirky, and the not so good.

Five Minutes with David Teh August 16, 2017 10:00

Earlier this year, David Teh published Thai Art: Currencies of the  Contemporary, which examines the transition of Thai contemporary art from a nationalist subjectivity to a postnational one. His analysis is set against the backdrop of the Thai monarchy’s waning sovereignty amidst political and economic turmoil.

Contemporary, which examines the transition of Thai contemporary art from a nationalist subjectivity to a postnational one. His analysis is set against the backdrop of the Thai monarchy’s waning sovereignty amidst political and economic turmoil.

In this edition of Five Minutes with…, Teh, an independent curator and Assistant Professor in the Department of English Language and Literature at the National University of Singapore, reveals how he first became involved in Thai contemporary art. He also shares how his curatorial experiences and intellectual inclinations have influenced his work, and the importance for Art History as a discipline to ‘decolonise’ itself.

What are the qualities of Thai contemporary art that drew you to study it, over other Southeast Asian nations with their own contemporary art?

I got to know about Thai contemporary art while living and working as a writer and curator in Bangkok. The book reflects that—I didn't go there looking to do academic research. That said, I already knew the Thai art scene was strong. Several Thais had built high profiles on the international exhibition circuit. But I was more curious about what was going on locally. As I got to know people, I learned about the burst of exciting, independent activity in the late 1990s—artists of my own generation were beneficiaries of that—but by the time I showed up, things had stagnated. The indie scene had run out of puff. The government was beginning to promote contemporary art but it was very tough for artists to make the work they wanted to make. So, I found I was most useful as an independent curator.

Tang Chang, Untitled, 1969, oil on canvas, 98 x 103 cm (Courtesy: Thip Sae-Tang/ Installation view. Image credit: Laura Fiorio / HKW)

It was never a choice between Thailand and other countries. I hadn't studied Southeast Asia or its history, and I got to know the region through the lens of Thailand, a place which—like Singapore—both belongs in the region and doesn't quite belong. Apart from their successes abroad, several things were distinctive about Thailand's artists. First, many were working confidently in non-traditional modes (eg. installation, video, conceptual art) even though those forms were not well supported by institutions or galleries. Second, there was often nothing very 'Thai' about their work, at least not visibly. This was in stark contrast with the art of the '90s, the bread and butter of the biennials sprouting in so many places. For me, national identity was a boring, hackneyed subject. And here was a generation of artists who weren't interested in national branding, yet who knew their cultural background would determine how their work was interpreted and valued. I found this tension fascinating, and it became a central concern of the book.

In the central chapters, you examine various forms of indigenous “currencies”—an agricultural symbology, a Siamese poetics of distance and itinerancy, and Hindu-Buddhist conceptions of charismatic power—and how contemporary art has converted them into other currencies. Why have you chosen to write about these particular forms of currency? Or, more specifically, what makes these very currencies the “national currencies” of Thai art?

The term 'currencies' is unorthodox in an art historical context. That discipline's habitual methods are failing: traditional, biographical approaches ended up in the bogus mythology of the singular creative genius; iconography charts the visible resemblances between one artist and another but in our networked, image-saturated environment, those patterns are unraveling; formalism imposes boundaries between various media that artists themselves no longer observe. In distilling some salient themes and concerns from Thai contemporary art, I was led by the artists I found most interesting. The challenge lay in figuring out how to historicise their work, and the 'currencies' I identified were a provisional solution, a way of tying artists and artworks into much larger social and cultural histories, while bypassing some of the pigeonholes of conventional art history. So, when contemporary artists adopt the theme of agriculture, for example, one might look back through eighty years of Thai modern art and find a few precedents. But agricultural imagery belongs to an ancient vocabulary of power in this part of the world, and it's more than just visual. That deeper, wider history illuminates today's art far more than recent art history can.

Similarly, Thai artists have attained social and intellectual cachet thanks to the patronage of the modern state and other institutions, but if you trace this 'charisma' within that institutional sphere, you only get half the story. For fifty years, the dominant 'national school'—the state academy (now Silpakorn University) set up in the 1930s—was the nerve centre through which all aesthetic traffic was routed, controlling access to resources and training, awarding coveted prizes and commissions, and setting artistic standards. Patronised by state and palace, Silpakorn was the main clearing house for artistic currencies, especially those stemming from the three institutional 'pillars' of Thai nationalism—religion, monarchy and nation. But since the 1980s ,its monopoly has crumbled: competing schools have been established, while globalisation has brought artists new sources of prestige and opportunity.

Near the entrance of Silapkorn University, which has served as the bastion of artistic pursuits in Thailand since the 1930s

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons).

What I call a 'currency' is a value an artist might intentionally rehearse—sometimes it's as simple as a visual cue, a choice of colours, a well-known symbol, a sign of the past or 'tradition'. But sometimes it's more abstract, or a projection onto their work by others. Some currencies are not visible, but are generated in the performance of being a modern artist. For instance, what does it mean to locate yourself in the provinces and address the orang kampung, using everyday materials and references, rather than the recognised idiom of 'fine art' from the national-institutional centre? This is a question that can be asked all over Southeast Asia. As we look beyond the obvious centres of production, there will be dozens of different answers, but also some overlaps and resonances.

I should stress that this book is by no means a comprehensive account—there are many currencies I haven't dealt with. I focused on the ones that have secured art's contemporaneity in Thailand, that is, those that qualify certain modern art as no longer simply modern, but 'contemporary'. International mobility was obviously a key currency, as it became more and more a fact of everyday professional life. But it also opens up new critical possibilities: when a work is shown in different places, it can carry different meanings and values. Artists are not naive about these differences; they exploit them, and the critic can examine this as a kind of arbitrage. It's no accident that the acceleration of Asian art's transnational exchange coincided with a regional financial crisis, sparked by the failure of the Thai baht in 1997.

How has your work as a critic and curator shaped how you approached your research for this book?

This is a crucial dimension of the book. From a traditional disciplinary standpoint it will seem methodologically unresolved, for it brings together all sorts of knowledge: plenty of historical (but not exactly 'art historical') context; critical responses to seeing exhibitions; and lengthy conversations with artists and curators that might be called 'ethnographic', though again, collected in somewhat heuristic and undisciplined ways. These are exactly the data sets of curatorial work, and Art History has been slow to take advantage of them. Making exhibitions, one develops a great reservoir of trust with artists and others who know and care about art. There's an intimacy you don't get from looking at catalogues—you learn things that can't be learned any other way.

In the West, Art History has ceded a lot of ground to various kinds of 'visual studies', and there's a burgeoning literature on histories of exhibition and curatorship. But in Southeast Asia, Art History is still getting clumsily on its feet. Universities have largely failed to seize an obvious opportunity. Meanwhile museums are going up with breathtaking speed, but without the necessary software to make them relevant. Until recently, research wasn't part of the curatorial skill set in Singapore, which is clearly the region's institutional centre of gravity. I think I'm very lucky that I found publishers who understood this patchy landscape, and that independent curators have been a crucial link in the knowledge chain. It's an imperfect science, to be sure, but ten or twenty years from now I think the book's idiosyncrasies, and its deficiencies, will tell us something about this moment.

Pratchaya Phinthong, Who Will Guard the Guards Themselves?, 2015. Lightbox, duratrans, and steel frame; 161 × 200 × 9 cm. Collection of Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (Courtesy of the artist and gb agency, Paris).

In the book, you challenged Singapore-born artist Jay Koh’s condescending response to Thai-born artist Rirkrit Tiravanija’s simulacrum of his New York apartment—titled “Tomorrow Is Another Day”—at the Kölnischer Museum, and contended with the view that representing one’s national polity of origin lies at the heart of the artistic enterprise. In your opinion, why is there a prevalence of this biased attitude towards national identification in the transnational sphere?

Its prevalence today may be put down to laziness, to certain ingrained habits of artists, writers and exhibition-makers. But there are clear historical reasons for it. In the late 1980s, contemporary art began to circulate transnationally with a new intensity, a whole new scale of exchange. There's a pair of excellent books on this moment, put out by Afterall under the title Making Art Global. One can pin this to the thaw of the Cold War and a certain narrative of globalisation, though upon close examination in a given place, one finds very complex processes at work. Nevertheless, this circuit became the basis of the transnational art system we see today. With this burst of circulation, audiences—particularly professional ones—came face to face with art from other worlds, from social, historical and aesthetic contexts about which they were often perfectly ignorant. Identity (and not exclusively national identity) was the primary interpretive crutch, providing a way in, some starting point for the uninitiated viewer confronted with Vietnamese, Peruvian, or Congolese contemporary art for the first time.

Southeast Asia's artists are still subject to the gravity of nation, much more than their counterparts in the Euro-American sphere whose institutions still dominate the art economy. In fact, when I travel in that post-national milieu, I'm the one insisting that the nation still matters! But as an interpretive support, it can only be one amongst many. Some artists still make art about national identity and belonging, either because those things are still material to their lives, or because they're on auto-pilot—it's what Southeast Asian art has done for twenty years; it's what made their mentors famous. But for most young artists in the region, national heritage and national problems are no longer front-of-mind. We have to find other ways of understanding their work and what it has to tell us, including what it might say about the place where it was made.

You recently curated an exhibition in Berlin, titled "Misfits". Are there any overarching ideas that you always try to put into your work, be it in curation or in writing?

David Teh introducing “‘Misfits’: Pages from a loose-leaf modernity” to visitors at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (Photo credits: Laura Fiorio / HKW).

I'm a card-carrying anti-essentialist. Most of my work is about unpicking and sabotaging big, overarching ideas. "‘Misfits’: Pages from a loose-leaf modernity" is about the process of canon formation that has been accelerated by the museum boom, and the recent discovery of Southeast Asia by first-world collecting institutions. I chose three modern artists on the cusp of canonisation, whose legacies haven't been mediated by national institutions, either because they deliberately kept their distance from the latter, or because the latter's narratives simply couldn't accommodate them. Two of them died in 1990: the Burmese artist and illustrator, Bagyi Aung Soe, and the Sino-Thai modernist Tang Chang. The third was Rox Lee, a Filipino filmmaker who is still very much alive and kicking. This grouping is unorthodox, but I liked how it opened up the question of what distinguishes 'modern' from 'contemporary'. (This is also a preoccupation of my book.) A growing curatorial workforce is busily constructing an overarching idea of 'Southeast Asian modern art'. It's important that we complicate the picture, and to that end, these 'misfits' are important circuit-breakers.

What sort of future conversations do you hope that this book will inspire?

In the broader (global) context, I think Art History is an ossified discipline, badly in need of renewal. Its academic mainstream is still cloistered, in Europe and North America; its conceptual toolkit is inadequate for the task of decentering and decolonising the history of modern art. Serious efforts are being made to adopt a more inclusive outlook—sometimes framed as 'world art history'—but encyclopaedic surveys only get you so far, and they don't make for compelling reading. To make Art History relevant again, its methods need to be deconstructed, its vocabularies need to be hacked. And we have to devise interdisciplinary but historically rigorous ways of furnishing context.

Closer to home, I hope the book's strengths and weaknesses will be picked apart and will provoke more critical discussion. It's a very charged environment in Thailand at the moment. The generals have their fingers in the dyke but the tide of history is pressing in. Managing a sensitive royal succession, the dictatorship has shut down the system of political expression; there's no public sphere, and criticism has become more and more dangerous. But at the same time, the country is gradually awakening from a long bout of historical naivety; people are reading more and debating more than they have for decades, largely thanks to the advent of social media. Thai artists are not known for taking strident political positions, yet the art world can be a relatively accommodating place for public discourse and argument, often flying beneath the radar of officialdom. I hope the book will be a conversation starter. Each chapter, each theme, is intended to open new ways of understanding contemporary art, and the social realities and histories it reflects.

Five Minutes with Lisandro E. Claudio July 18, 2017 15:30

In March earlier this year, Lisandro E. Claudio published Liberalism  and the Postcolony: Thinking the State in 20th-Century Philippines. Prior to this groundbreaking work, historical scholarship on liberalism in the Philippines was largely unexplored. In this edition of Five Minutes With…, we chat with Claudio—an Associate Professor of History at Manila’s De La Salle University more affectionately known as Leloy—about how his book was born, his experience of writing in Kyoto, free dinners, politics, and his revolutionary of a grandmother.

and the Postcolony: Thinking the State in 20th-Century Philippines. Prior to this groundbreaking work, historical scholarship on liberalism in the Philippines was largely unexplored. In this edition of Five Minutes With…, we chat with Claudio—an Associate Professor of History at Manila’s De La Salle University more affectionately known as Leloy—about how his book was born, his experience of writing in Kyoto, free dinners, politics, and his revolutionary of a grandmother.

Although your book is concerned with Philippine politics and intellectual history, it was written during a two-year postdoctoral fellowship in Kyoto. How did that distance help shape your critical views?

I’ll use this question as an opportunity to thank my host institution. The Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS) at Kyoto University was the perfect place to write a book on a Southeast Asian state. For one, it is close enough to allow regular trips back to the region. So, in a sense, I actually did not have much distance. What I had was time to think and write amid the monastic yet urban atmosphere of Kyoto, while being able to easily book a flight to the Philippines if I needed to plug gaps in the research.

Secondly, CSEAS does Southeast Asian Studies for Southeast Asians. Its sensei have solid connections with the region, and they have a clear idea of their audience. My primary audience has been and will always be Filipinos, who think about and debate the future of our political community. Kyoto reinforced this. It is not a place that forces you to get into an academic rat race, where you aim to publish with American publishers while jumping on the latest American trend (whatever that may be—I think it’s affect theory at the moment). I’d like to think that because of the culture of CSEAS, I produced a book for Filipinos and Southeast Asians, written without paying obeisance to trends in cultural theory. And because I was in Kyoto, I was encouraged to publish in the premier academic press in Southeast Asia (that’s you guys!), and co-publish with the premier academic press in the Philippines (Ateneo de Manila University Press). If people outside my intended audiences wish to pick up the book because they are interested in liberalism, of course, that would make me happy. They can buy something from Singapore or Manila. But the primary goal is to talk to Filipinos concerned about the Philippines qua state.

Japan is wonderful because, like the US, it has money for research, but without the trendiness. And this was a very square, untrendy book about a philosophical idea that is not as exciting and revolutionary as postcolonial theory or even good ole’ Marxism. Moreover, if I were in the US, I might have had to factor identity politics into the manuscript, since Filipinos there are almost obligated to ‘interrogate’ or ‘problematize’ their subjectivities. But in Japan, you do what you want. So I wrote a book that conceived of “Filipino” as a political community as opposed to cultural identity. I wanted to write a book about civic nationalism/patriotism, unabashedly anchored on conceptions of the state.

Finally, Kyoto provided me the best mentorship. I sped through my PhD in three years in Australia, and felt a bit ‘undercooked’ at the end of it—not because my teachers failed to guide me, but simply because I was in such a rush to complete the degree (I was homesick in the beginning). Writing this book felt like writing a second dissertation. In the process, I benefited greatly from CSEAS’ Caroline S. Hau, who made me think about the relationship between liberalism and our vague notions of who the ‘elite’ are (while buying me multiple dinners). She also made me, almost against my will, think about liberalism and macroeconomics, which produced the chapter on Salvador Araneta. I owe so much to Carol for gently nudging me out of my comfort zone.

The nationalist economist Salvador Araneta pictured with family at Far East Air Transport, Incorporated, n.d. (Image credit: Manila Times Photo Archive, Rizal Library, Ateneo de Manila University).

You mention in your book’s introduction that you are interested in “bureaucratic writers and pencil-pushers, who aided the transition of a nation from colonial rule to independence” over other groups with nation-building interests. What attracted you to these particular perspectives of liberalism and postcolonialism?

As I said earlier, I’m attracted to, for lack of a better term, squareness. This is why a section of the introduction is called “a defense of boring politics.” Why must academic work have to be sexy or provocative? Especially when the topic is a postcolonial society like the Philippines. My sense is that, since academics like me are square personalities anyway, we should also write about square topics, like, yes, the history of pencil-pushers. Come on, how many academics are really revolutionaries? And yet some of them write like they’ll be the next Che Guevara. I’m only being slightly facetious here.

In Southeast Asian studies, we’ve been so obsessed with insurgencies, millenarian movements, anarchism, mythological and magical interpretations of politics, et cetera. I almost feel like there is an element of self-Orientalization. Maybe we should also talk about reason and Enlightenment and not be ashamed of it.

I think there is a need to grapple with Southeast Asian modernities that are in dialogue with Western Enlightenment. Unearthing the history of the Philippine liberal tradition was my way of doing this. I have a number of friends in Thai studies who are doing similar things, looking at Thai liberalism. I hope we can push the limits of Southeast Asian studies and write more histories of square people.

You also observe that, in Filipino history, liberalism is often excluded from the records despite its close ties to Philippine nationalism. How did you come into this insight and what was the first step you took in addressing this exclusion?

Yes, look at our national hero José Rizal, for example. With perhaps the exception of John N. Schumacher and Nick Joaquin, very few writers talk about him as a liberal. Always a nationalist, but never a liberal. But he was so obviously a liberal! The guy was perennially talking about the rights of man and the need to defend liberty. He even wrote numerous essays against the absolute power created by martial law (how proto-anti-Marcos, right?).

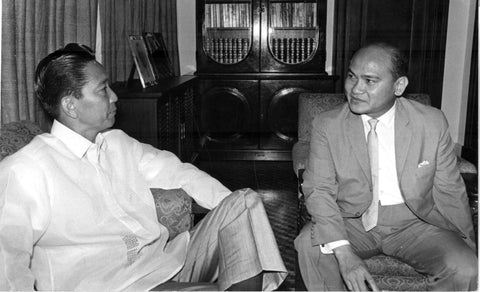

Former president Ferdinand Marcos (left), who ruled the Philippines from 1965 to 1986, meeting the educator and statesman Salvador P. Lopez, n.d. (Image credit: Manila Times Photo Archive, Rizal Library, Ateneo de Manila University).

I don’t remember exactly how I came to my insight about the exclusion of liberalism from the national narrative. But I do remember my other mentor, Patricio Abinales, once asking me—way before I decided to write this book—why nobody had written a history of Philippine liberalism. I guess I never got that question out of my head. So I ended up working on this book.

Maybe the exclusion of the liberal tradition comes from the fact that much of our country’s liberalism is of American vintage (although, as I mentioned earlier, Rizal’s generation was already liberal). In the 1970s, Philippine historiography fell prey to a rabid, almost ethnocentric nationalism that dismissed anything from the US or the West as external to the Philippine experience, and that included liberalism. It had a very insidious effect, and the rhetoric survives today, mouthed, no less, by our dictatorial baby boomer president, Rodrigo Duterte.

You know what makes my blood boil? When Filipino politicians, especially supporters of the president, say Filipinos should challenge “Western liberalism.” As if liberalism were so external to our national experience.

How do we go beyond the exclusion of liberalism? I’m very practical about this. Perhaps we should stop obsessing about the provenance of an idea. Instead, maybe we should ask if an idea, regardless of where it comes from, is a good one. In the book, I tried to make the case that liberalism is a good idea for the Philippines, especially during the age of what commentators have called “Dutertismo.”

What were the major obstacles you faced in sourcing material for your book?

Nothing much. The advantage of intellectual history is that you work largely with published material. The most difficult chapter to research was the one on Salvador P. Lopez, because he lacked vanity. The rest of the intellectuals in the book loved to self-publish their speeches, but SP was too self-effacing (unlike his hucksterish, but formidable, mentor, Carlos P. Romulo) to play that game. With the help of my friend Aaron Mallari, I was able to dig through the SP Lopez papers in the University of the Philippines Diliman. It’s a treasure trove, actually. More people should go there—if they can take the heat and the dust.

SP Lopez addressing students, teachers, and staff during the Diliman Commune of February 7, 1971. (Image credit: Manila Times Photo Archive, Rizal Library, Ateneo de Manila University)

In your afterword, you offer a fifth liberal to join the four historical protagonists in your book—your maternal grandmother, Rita D. Estrada, who had been a professor at the University of the Philippines. Based on your tender and illuminating portrait of her, she was a remarkably charming and extraordinary woman. Would you consider writing a book on her one day?

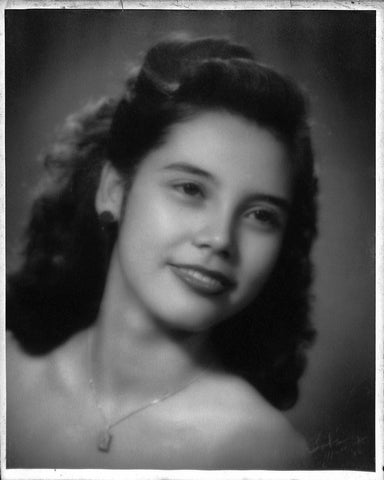

Rita D. Estrada, the author’s grandmother and a revolutionary liberal in her own right. (Image credit: Lisandro E. Claudio)

Thank you, I tried to conjure the Lola Rita of my memories, while representing her as an intellectual in her own right.

But, no, I don’t think I'd be able to write a full book about her. There isn’t enough material. My lola was a quiet intellectual who did not leave behind a lot of writings. The epilogue of the book is enough of a tribute to her, and enough naval-gazing for me. I enjoyed writing it, though, and it made my mom cry.

Five Minutes with Andrea Benvenuti June 21, 2017 12:00

With the recent publication of his new book, Cold War and Decolonisation: Australia’s Policy towards Britain’s End of Empire in Southeast Asia, Andrea Benvenuti seeks to challenge popular views—and misconceptions—of Australian relations with its neighbouring region during the Cold War. Moreover, Benvenuti, a senior lecturer in International Relations and European Studies at the University of New South Wales, offers a fresh and incisive look at the Australian perspective during the emergence of independent Southeast Asian nations and the collapse of British colonial rule.

With the recent publication of his new book, Cold War and Decolonisation: Australia’s Policy towards Britain’s End of Empire in Southeast Asia, Andrea Benvenuti seeks to challenge popular views—and misconceptions—of Australian relations with its neighbouring region during the Cold War. Moreover, Benvenuti, a senior lecturer in International Relations and European Studies at the University of New South Wales, offers a fresh and incisive look at the Australian perspective during the emergence of independent Southeast Asian nations and the collapse of British colonial rule.

In this edition of Five Minutes With …, Dr Benvenuti debunks the myths surrounding Australian political history, particularly those regarding the Menzies government, transplants his Cold War observations into the current political climate, and shares his upcoming projects.

What attracted you to the Australian policy perspective of the Cold War?

One of the enduring myths in Australian political history is that Australia failed to pursue an independent foreign policy in Asia during the early Cold War. As the story goes, under the Liberal–Country Party Coalition government of Sir Robert Menzies (1949–66) Australia overplayed the threat of international communism and became closely aligned with the United States and Britain in an effort to contain the spread of communism in Asia. However, by identifying itself too closely with American and British Cold War policies in Asia, the Menzies government, it is said, foreclosed any chance of engaging meaningfully with its neighbouring region and of developing a distinctive regional role for Australia. The underlying assumption here is that Australia would probably have been better off pursuing a neutralist foreign policy.

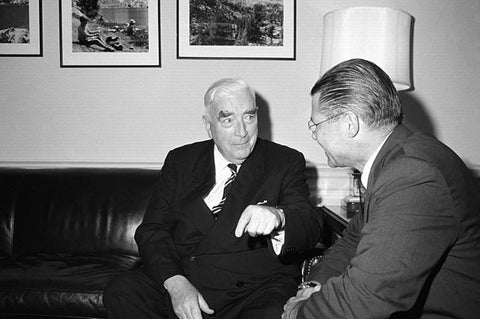

Robert Menzies (left) meets with US Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara at the Pentagon in 1964

(Image credit: Wikimedia Commons).

I have never been persuaded by these kinds of arguments and I thought I ought to find out more. I hope my book will provide a less distorted appreciation of Australia’s Cold War role in Asia and thus make a significant contribution to a better understanding of Australian policy concerns and interests, in a region of paramount strategic, political and economic importance.

What insights does your book offer on Australian foreign policy and relations with Southeast Asia that other historians may have neglected?

Another enduring myth in Australian history and politics is the idea that the Menzies years stand as a blot on the relationship between Australia and Southeast Asia. In Australian universities, scores of undergraduate and postgraduate students are taught to believe that Menzies’ conservative government had little interest in forging close and enduring links with Southeast Asia. According to the prevailing academic wisdom (one that is often embraced with gusto by the Australian media), Menzies’ Anglophilia and his keenness to nurture close ties with Australia’s ‘great and powerful friends’ (the US and Britain) prevented Australia from developing closer regional ties. Only with the arrival of Gough Whitlam at The Lodge (the Australian Prime Minister’s residence in Canberra) in 1972 did Australia begin to seriously engage with the region.

Nothing, of course, could be farther from the truth and my book shows just how grotesque this view is. Under Menzies, Australia pursued a policy of active and sustained regional engagement. Southeast Asia’s political stability and economic prosperity were of utmost importance to Menzies’ Australia, and the Liberal–Country Party government acted accordingly by placing regional engagement at the forefront of its foreign policy.

A clip of Gough Whitlam’s 1974 visit to the Philippines, which was part of a Southeast Asian tour to strengthen ties between the region and Australia. Whitlam also visited Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Laos, and Burma. (Source: Whitlam Institute YouTube Channel; footage courtesy of the National Film and Sound Archive and the National Archives of Australia [NAA 4423/31]).

The Menzies government expressed approval of Malaya and Singapore’s bids for merger and independence from British rule. How has this endorsement shaped Australia’s relations with Malaysia and Singapore since the Cold War era?

It has no doubt contributed to drawing Australia closer to Malaysia and Singapore, and forging an enduring and deep relationship with them.

In light of increasing nationalism amongst certain world powers, what lessons on navigating security and international relations from your book might be applicable today?

It is often difficult to compare the world of the 1950s or 1960s with our own. When I talk to my undergraduate students about the early Cold War years in Southeast Asia, I sometimes feel as if I am talking to them about ancient history, given that so much has changed at international and regional levels since then. With this proviso in mind, I venture to offer one possible lesson: as the history of modern Singapore and Malaysia clearly shows, regional political stability and economic prosperity are best maintained through a continuing and robust Western engagement with the region and vice-versa. Beijing’s version of ‘Asia for the Asians’ is really in no one’s interest.

What are your current research projects?

I am currently working on two projects: the first deals with Western (American, British and Australian) responses to the emergence of non-alignment in Asia during the 1950s and early 1960s. The second examines the role and impact of Western military power and strategic foreign policy in the ordering and re-ordering of Asia between 1919 and 1989. It is a collaborative international project sponsored by the Department of History at the National University of Singapore and led by Professor Brian Farrell.

The Challenges of Mapping Singapore’s Permanent Territorial Transformations June 2, 2017 14:30

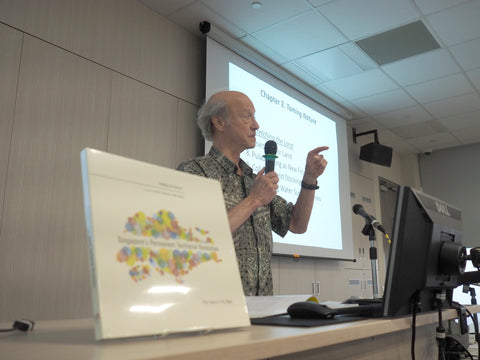

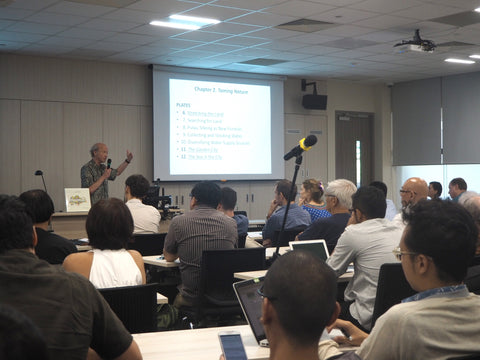

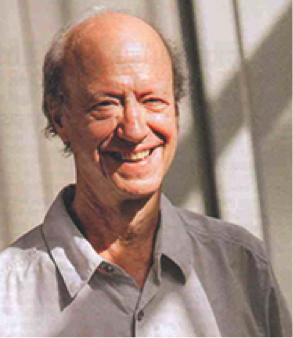

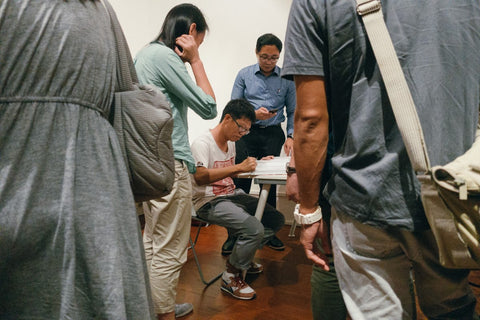

On May 29, Professor Rodolphe De Koninck launched his latest book, Singapore’s Permanent Territorial Revolution: Fifty Years in Fifty Maps, at the National University of Singapore’s Asia Research Institute. As the third book in a series of Professor De Koninck’s noted atlases—the first was released in 1992, and the second, in 2008—the event saw a huge turnout consisting of local artists, students, heritage advocates, and established local academics.

(Image credit: Sebastian Song)

Professor De Koninck described his early fascination and subsequent research on farmers and vegetable traders in a post-colonial Singapore. He related how his series of atlases was borne out of an unnerving sense of displacement he felt as a returning researcher, having lost his bearings many times in a constantly developing Singapore. In particular, he recalled being struck by the aspirations of his Singaporean friends who, despite having their daily lives dramatically altered by the massive urban transformations of the late 20th century, had taken in all these changes without complaint.

“No other city in the world experiences such rapid and systematic transformations.”

(Image credit: Sebastian Song)

Comparing the urban developments that have unfolded in capitals across the world, Professor De Koninck declared that the territorial evolutions of Singapore are of an unprecedented scale, subsequently proposing the hypotheses at the heart of his book: (1) the resignation of Singaporeans towards socio-economic transformations are in part due to the permanent transformations of the urban landscape, and more importantly, (2) the transient nature of local spaces allows for only a single dimension of territorial allegiance: that of the Singaporean state.

“Nothing is sacred, nothing is permanent, nothing is culturally untouchable.”

(Image credit: Patricia Karunungan)

Bringing the audience into a preliminary view of his book, Professor De Koninck presented the nature of territorial alienation faced by Singaporeans through a vast and fascinating series of maps. These included: the diachronic mapping of changes in the population spread, the distribution of religious places of worship, military training grounds, burial sites and the like. The constant marginalisation, and in some cases, destruction, of culturally sacred spaces, he argued, has precipitated a cultural phenomenon in which “nothing is sacred, nothing is permanent, nothing is culturally untouchable”.

Throughout the talk, Professor De Koninck also debunked several myths—such as that of land scarcity—and raised keen observations surrounding changes in the territoriality and topography of Singapore, such as the non-intentional softening of violent urban transformations in the effervescence of nature alongside roads.

(Image credit: Sebastian Song)

At the end of the talk, Professor De Koninck and members of the audience engaged in a heated Q&A session where they grappled with issues surrounding territory and topography, the alienation of heritage and history from individuals, as well as the politics of identity.

(Image credits: Sebastian Song)

In light of the increasing and galvanising public outcry surrounding the demolition of sites such as Bukit Brown Cemetery, the lessons to be gleaned from Singapore’s Permanent Territorial Revolution, in particular, its comprehensive insights into a Singapore rarely remembered, are now more relevant than ever.

The book is available for purchase in-store at NUS Press and on our online webstore.

Author Events: Ann Wee and Rodolphe De Koninck May 19, 2017 12:00

We’re pleased to announce that two NUS Press authors will be having events in Singapore towards the end of May.

Meet Ann Wee at Kinokuniya (May 27)

Mrs Ann Wee, author of A Tiger Remembers: The Way We Were in Singapore,  will be appearing at Kinokuniya Main Store (Ngee Ann City) on Saturday, May 27 at 4pm.

will be appearing at Kinokuniya Main Store (Ngee Ann City) on Saturday, May 27 at 4pm.

Born in the year of the Tiger, Ann Wee moved to Singapore in 1950 to marry into a Singaporean Chinese family. Affectionately observed and wittily narrated, A Tiger Remembers: The Way We Were in Singapore brings to life Singapore’s social transformation.

A finalist for ‘Best Non-Fiction Title’ for the 2017 Singapore Book Awards, this book captures the things that Ann Wee remembers but history books have left out – questions of hygiene, terms of endearment, the emotional nuance in social relations, rural clan settlements, migrant dormitories, and more.

(Image credit: Ann Wee)

Admission is free—just drop by the Kinokuniya Main Store at 4pm next Saturday!

Talk by Prof Rodolphe De Koninck: The Challenges of Mapping Singapore’s Permanent Territorial Transformations (May 29)

Rodolphe De Koninck will be presenting a talk at the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore on Monday, May 29, 4 – 6.30pm.

Over a period of nearly 25 years, Singapore’s territorial transformations have  been the object of three atlases by Professor De Koninck. The first appeared in 1992, the second in 2008, and Professor De Koninck’s latest book, Singapore’s Permanent Territorial Revolution: Fifty Years in Fifty Maps will be published at the end of the month.

been the object of three atlases by Professor De Koninck. The first appeared in 1992, the second in 2008, and Professor De Koninck’s latest book, Singapore’s Permanent Territorial Revolution: Fifty Years in Fifty Maps will be published at the end of the month.

Ever since Singapore became an independent nation in 1965, its government has been intent on transforming the island’s environment. This has led to a nearly constant overhaul of the landscape, whether still natural or already manmade. No stone is left unturned, literally, and, one could add, nor is a single cultural feature, be it a house, a factory, a road or a cemetery.

(Image credit: Wilson Pang)

By constantly “replanning” the rules of access to space, Professor De Knoninck shows that the Singaporean State has been redefining territoriality, even in its minute details. This is one reason it has been able to consolidate its control over civil society, peacefully and to an extent rarely known in history.

The talk will be devoted to the presentation of how Singapore’s Permanent Territorial Revolution was produced and, more importantly, to a summary and explanation of its contents and conclusions.

Admission is free but you are encouraged to register your interest with the Asia Research Institute.

Two NUS Press Titles Shortlisted for the 2017 Singapore Book Awards April 7, 2017 10:00

We are pleased that two NUS Press titles have been shortlisted for two categories in this year’s Singapore Book Awards.

Best Non-Fiction Title Finalist

A TIGER REMEMBERS: THE WAY WE WERE IN SINGAPORE

In A Tiger Remembers, Ann Wee, born in the Year of the Fire Tiger, pays homage to the things history books often deem insignificant — questions of hygiene, terms of endearment, the emotional nuance in social relations, stories of ghost wives and changeling babies, rural clan settlements and migrant dormitories, the things that changed when families moved from squatter settlements into public housing.

In A Tiger Remembers, Ann Wee, born in the Year of the Fire Tiger, pays homage to the things history books often deem insignificant — questions of hygiene, terms of endearment, the emotional nuance in social relations, stories of ghost wives and changeling babies, rural clan settlements and migrant dormitories, the things that changed when families moved from squatter settlements into public housing.

Affectionately observed and wittily narrated, with a deep appreciation of how far Singapore has come, this book brings to life the story of social change through a focus on the institution of the family. The late S. R. Nathan is "certain that this memoir will be absorbed in society and will serve as a conversation piece to learn about the various aspects of our past heritage and culture."

Best Illustrated Non-Fiction Title

CHINESE EPIGRAPHY IN SINGAPORE, 1819-1911

The history of Singapore's Chinese community has been carved in stone and wood throughout the country. Professor Kenneth Dean and Dr Hue Guan Thye's Chinese Epigraphy in Singapore, 1819-1911 looks specifically at 62 Chinese temples, native place associations, clan and guild halls, where epigraphs were made between 1819 to 1911 are still found today. Over the course of four years, Professor Dean and Dr Hue visited more than 400 locations to record, photography, analyse and translate these inscriptions into English. These epigraphs are now faithfully reproduced with more than 1,300 illustrations in these two volumes.

The Singapore Book Awards is an industry award for books published in Singapore. Into its third edition, the awards shine the spotlight on the quality of published works and celebrate the achievements of the local publishing industry.

This year’s award winners will be announced at an Awards Ceremony at Pan Pacific Singapore on April 20, 2017. For more information about the Singapore Book Awards and other award categories, click here.

Five Minutes with Brian Bernards November 22, 2016 15:00

In this special edition of our author-interview series, Professor Philip Holden from the National University of Singapore conducted an email interview with Professor Brian Bernards on the occasion of the publication of the Southeast Asian edition of Writing the South Seas: Imagining the Nanyang in Chinese and Southeast Asian Postcolonial Literature. An assistant professor at the University of Southern California, Bernards works in three languages – English, Chinese, and Thai—and his book thus gives a revisionary perspective on the literatures of the region, and indeed the way in which we imagine Southeast Asia itself.

University of Singapore conducted an email interview with Professor Brian Bernards on the occasion of the publication of the Southeast Asian edition of Writing the South Seas: Imagining the Nanyang in Chinese and Southeast Asian Postcolonial Literature. An assistant professor at the University of Southern California, Bernards works in three languages – English, Chinese, and Thai—and his book thus gives a revisionary perspective on the literatures of the region, and indeed the way in which we imagine Southeast Asia itself.

Professor Holden's and Professor Bernards' exchange was first published on singaporepoetry.com. We are pleased to present some excerpts of their lively discussions:

Philip Holden: As someone who has been studying auto/biography, I’m always interested in the life stories of scholars. What drew you to study Chinese and Thai? And what fostered your interest in the literatures of Southeast Asia?

Brian Bernards: When I was 9 years old, a family from Shanghai (a father, mother, and their 2-year-old daughter) moved in with my family at our home in Minneapolis. The father was studying engineering at the University of Minnesota, and the mother, who later went on to study accounting, became our live-in babysitter. On occasion, our two families had meals together, and the boiled dumplings (shui jiao) our sitter cooked became quickly my new favorite dish. Our good friends from Shanghai lived with us for about two years, when the father graduated and found a plush job in Milwaukee. Starting high school about three years later in 1992, I opted to take Mandarin because of my prior exposure to Chinese culture (and cuisine!). I first traveled to mainland China in 1998, where I studied for a year at Sichuan University in Chengdu. My language professor recommended Chengdu because she had done research there, she knew I wanted to tread beyond the typical path of studying in Beijing, Shanghai, or Taipei, and, most importantly, she knew I would like the spicy ma-la food there. Living and attending school in Chengdu certainly opened my eyes, and my taste buds, to new experiences, flavors, and possibilities.

PH: Given your exposure to different disciplines, what are your thoughts on inter-disciplinary studies?

BB: I have always enjoyed literature (especially fiction and poetry), music, and film. As a student and traveler, I felt I could better connect with a place, a culture, a society, and its history through the very personal stories and creative imagination conveyed in fiction and memoirs by authors who were from or who were very familiar with that society. While Southeast Asian studies in the US is largely a social science-oriented field, I was fortunate to take history and anthropology classes as an undergraduate from professors who, rather than assigning dry textbook readings, assigned novels by authors such as Pramoedya Ananta Toer, José Rizal, Duong Thu Huong, Ma Ma Lay, and Kukrit Pramoj, to be read in conjunction with course lectures. I was very inspired by this approach to history and cultural studies, not only because it put the human impact of historical events and social transformations in relatable narratives rather than abstract figures, but also because the micro-histories we encountered in such literary narratives often challenged or even contradicted the standard interpretations and “big picture” perspectives taken for granted in the official histories. I am grateful to my teachers for cultivating the approach that would stick with me as I moved forward into graduate studies.

PH: What was the process of writing Writing the South Seas like?

BB: Writing the South Seas began as a way of combining my interests and background knowledge in modern Chinese literature, Southeast Asian studies, and postcolonial literary theory in an attempt to make a novel contribution, and hopefully a type of critical intervention, in each field. I felt the varying approaches from these different fields could be mutually illuminating in ways that the disciplines had yet to sufficiently consider. Mainly, I sought to bring a Southeast Asia-centered perspective to the study of literatures in Chinese on and from the region. Luckily, I conceived the project at the time that Sinophone studies was emerging and bringing about a sea-change in the modern Chinese literary field. Sinophone studies not only emphasizes cultural networks across national and ethnic boundaries, but also seeks to situate such networks locally in their multilingual milieu. In this sense, my interests in Anglophone literature and Thai-language literature from Southeast Asia, which might have otherwise been seen as irrelevant or marginal to modern Chinese literary studies, could provide an insightful comparative perspective that showcased the cross-lingual interactions and relationships of these Sinophone literary networks. I owe a significant intellectual debt to the pioneering work of Shih Shu-mei in this regard.

PH: The cover of your book will have a particular resonance for many Malaysians and Singaporeans. Could you explain this?

BB: I really have you to thank for this, Prof Holden, as you were the first person to recommend Suchen Christine Lim’s novel Fistful of Colours to me when I began researching Anglophone authors in Singapore. As you know, at the end of the novel, the protagonist returns to Kuala Jelai, her home village in Malaysia, from Singapore, and she becomes moved viewing the large wall murals while waiting for her train at the Tanjong Pagar Railway Station. When I read this passage, I wanted to see the murals myself, though at the time I had no idea they would later provide the source material for the cover of my book.

That was before the station closed. When it was operational, the station, along with the Keretapi Tanah Melayu (KTM) railway tracks, was an important living legacy of the intimate relationship, common colonial history, and shared culture between the two countries. Now that it is closed, it can only serve as a “heritage site” – a relic or a reminder of that past. For a lot of Malaysians and Singaporeans who grew up when the two societies were more integrated, Tanjong Pagar is bound to be a source of nostalgia, especially because it conjures a more rustic landscape and older colonial architecture that contrasts with the image of Singapore as a city of glistening skyscrapers and squeaky-clean air-conditioned malls. I think this nostalgic sentiment regarding the railway station is quite obvious in “Parting,” director Boo Junfeng’s contribution to the omnibus film, 7 Letters: he uses the space of Tanjong Pagar to tell the story of an interethnic romance against the backdrop of racial riots in the 1960s.

Interior of Tanjong Pagar Railway Station, 2010

(Image credit: Jacklee, Wikimedia Commons)

Of the six triptych murals in the station, the one with the commercial maritime focus showing the harbour was the most relevant to my book in its entirety, so I commissioned an image of that mural for the cover. The different types of ocean vessels in the image, from a sampan to a junk to a passenger steamship, really captured the varying modes of maritime crossings and convergences that the Nanyang has historically signified. And it’s beautifully done.

****

NUS Press would like to thank singaporepoetry.com's founding editor, Koh Jee Leong for granting permission to republish these excerpts.

Sayonara, 2016 Singapore Writers Festival November 18, 2016 17:00

With Japan as its country focus, the 19th Singapore Writers Festival came to an end last weekend after ten action-packed days of literary talks, discussions, music, and performances.

NUS Press was proud to have been one of five publishers featured in The Paper Trail, a backroom tour of Singapore publishers led by poet Yong Shu Hoong on November 5. Our director Peter Schoppert addressed a group of about 30 people and gave a quick overview of the history of the university press, and how it came to establish a foothold in the academic publishing scene in Asia.

(Image credit: Caroline Wan, National Arts Council)

(Image credit: Yong Shu Hoong)

Author Yap’s poems and short stories, and Goh Poh Seng’s memoir and novel, If We Dream Too Long, were naturally snapped up by some tour participants.

(Image credit: Caroline Wan, National Arts Council)

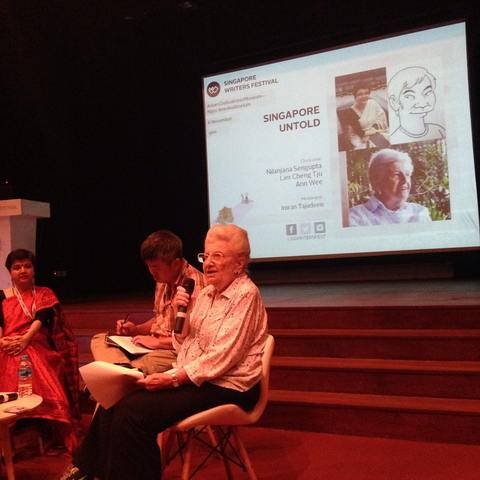

On November 6, two of our authors, Lim Cheng Tju, co-author of The University Socialist Club and the Contest for Malaya: Tangled Strands of Modernity, and Mrs Ann Wee, author of A Tiger Remembers: The Way We Were in Singapore, appeared on a panel alongside Nilanjana Sengupta at the Asian Civilisations Museum to share how everyday experiences, lesser-known stories, and oral histories are crucial for a better understanding of Singapore's past.

(From left to right) Nilanjana Sengupta, Lim Cheng Tju and Ann Wee

(Image credit: Chye Shu Wen).

Last but not least, we caught the matinee performance of The Finger Players’ love-letter to Singapore’s literary history, Between the Lines: Rant and Rave II. It was a delight to watch Serene Chen and Jean Ng act out key literary milestones in the development of Singapore’s cultural landscape. We were thrilled to have had some of our publications and authors (Edwin Thumboo, Arthur Yap and Goh Poh Seng to name just a few) featured in this play.

(Image credit: Chye Shu Wen)

At the end of the play, the stage became a pop-up shop for 30 minutes and it was heartening to see audience members stream down to the stage to browse through and purchase the books that were featured in the play.

(Image credit: Chye Shu Wen)

We look forward to the 20th edition of the Singapore Writers Festival, which is set to take place from 2–13 November 2017.

NUS Press at the 2016 Singapore Writers Festival November 4, 2016 11:00

NUS Press is pleased to be participating in this year's Singapore Writers Festival (SWF)! Themed "Sayang," the festival will feature close to 320 writers, speakers and performers between November 4–13.

To celebrate, we are offering special prices for this selection of titles!

We will also be featured in these main events:

Singapore Untold | 6 Nov, 1–2pm |

Asian Civilisations Museum (Ngee Ann Auditorium)

Our authors, Ann Wee, a pioneer of social work education in Singapore and author of A Tiger Remembers: The Way We Were in Singapore, and Lim Cheng Tju, co-author of The University Socialist Club and the Contest for Malaya: Tangled Strands of Modernity, will be appear in this panel alongside Nilanjana Sengupta to discuss why they have written stories that are often not found in Singapore history textbooks. They will also talk about their experience of uncovering and writing these stories.

You can attend this event with a SWF Festival Pass (S$20), which is available via SISTIC.

Ann Wee (left) and Lim Cheng Tju (right) (Image sources: Singapore Writers Festival).

Between the Lines: Rant & Rave II | 4–6 Nov, various times |

School of the Arts (SOTA) Studio Theatre

Simultaneously a crash course in, and a love letter to SingLit, Between The Lines: Rant & Rave II will take you on an odyssey of the evolution of the English-language literature scene in Singapore through the decades. Actors Serene Chen and Jean Ng as they take on the roles of real-life poets, novelists, publishers and many more in this loving tribute to the written word.

NUS Press is pleased that a number of books and authors we have published (from Edwin Thumboo's 1973 book, Seven Poets: Singapore and Malaysia, to Arthur Yap's Collected Poems) will be featured in this performance!

Between the Lines was commissioned by SWF and is presented by The Finger Players. Tickets (S$35) are available via SISTIC.

Serene Chen and Jean Ng rehearsing for "Between the Lines" (Image courtesy of The National Arts Council).

The Paper Trail: A Backroom Tour of Singapore Publishers (SOLD OUT) |

5 Nov, 9am–1pm | Various locations

Launch of "Nature's Colony" at the Singapore Botanic Gardens October 21, 2016 11:00

Timothy Barnard launched his latest book, Nature’s Colony: Empire, Nation and Environment in the Singapore Botanic Gardens, at the Singapore Botanic Gardens on October 14, as part of the Gardens' regular speaker series.

(Photos courtesy of Sebastian Song)

Professor Barnard centred his talk around the history of the Gardens and its broader impact beyond its bounadries in environmental, political, and

social terms.

(Photos courtesy of Sebastian Song)

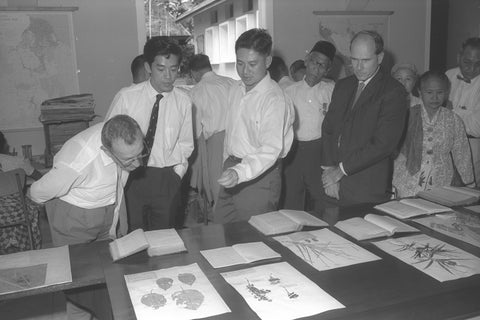

Professor Barnard explained that the botanic gardens was established as a private park between 1869 and 1874. By the early 1870s, the British realised that it had the potential of becoming a key colonial institution because imperial botany was seen as a tool that could strengthen empire (i.e. rubber seeds could be harvested in Singapore and Malaya, which could then be traded as a commodity).

The ever-changing position of the Singapore Botanic Gardens in society and politics over time has also often been overlooked: Professor Barnard emphasised the Gardens' precarious position as a colonial institution in a decolonialising society in a post-Merdeka era.

Humphrey Burkill, Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens from 1957 to 1969, leading a tour of government officials at the opening of the “renovated” herbarium in October 1964 (Source: Ministry of Information and Arts Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore).

One of the highights of the talk was a segment on Henry Ridley, the Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens between 1888 and 1912. Ridley was seen as “mad” by many of his contemporaries within the colonial government in Singapore due to his quirks and views of how the Singapore Botanic Gardens should be developed.

Ridley accomplished a lot during his tenure as director—from overseeing the set up of a short-lived zoo (1875-1905), to the establishing an Economic Garden within the park. Ridley also had the foresight to see that planting oil palm would have economic advantages for the region.

Henry Ridley with a small panther (Image reproduced with the kind permission of the Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew).

The talk was followed by a lively question and answer session that was moderated by the Group Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens, Dr Nigel Taylor.

(Photo courtesy of Sebastian Song)

At the end of the talk, many queued up patiently for Barnard to sign their copies of Nature’s Colony.

(Photos courtesy of Sebastian Song)

We would like to thank the Singapore Botanic Gardens for hosting the launch. If you would like to hear snippets of what Barnard said that day, you can check out his interview with talkshow host, Michelle Martin, on 93.8 Live’s Culture Café here, where he discussed his book and the history of the Gardens.

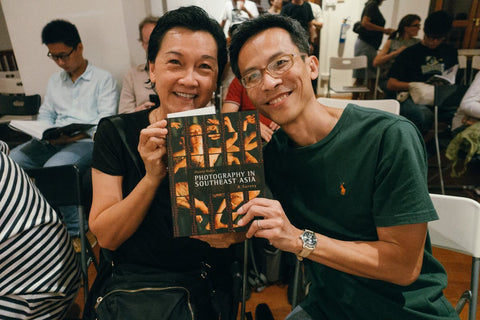

Launch of "Photography in Southeast Asia" in Singapore October 18, 2016 17:00

Zhuang Wubin's Photography in Southeast Asia: A Survey was launched at Objectifs Centre for Photography and Film on October 13, 2016. The launch featured a dialogue between Zhuang and famed street photographer, Chia Aik Beng, followed by a lively question and answer session.

(Photo courtesy of Kevin Lee)

Zhuang and Chia discussed the influence and impact social media has had on photography. When asked by Zhuang about the advantages and disadvantages of using Instagram as a platform for showcasing work, Chia said, "Instagram is a social media platform; it is not a photo gallery or website. If I'm on a project, I will share some images [on my Instagram account], to tease people and then direct them to my website. This is how I distribute information."

For a detailed transcript of what was discussed during the book launch, you can read Invisible Photographer Asia's coverage of it here. We are grateful to Objectifs for sponsoring the venue for this book launch, and to Kevin Lee for being the official photographer of the event.

NUS Press Book Launches in October 2016 October 7, 2016 15:00

October is looking up to be a very busy but exciting month for us with three book launches taking place in Singapore!

|

BOOK LAUNCH & DIALOGUE

|

|

AUTHOR TALK & BOOK LAUNCH

|

|

BOOK LAUNCH

|

International Translation Day: Five Minutes with Frank Palmos September 30, 2016 09:20

Why does translation matter?

The rise of works being translated into English in recent years seems to have made that question a rhetorical one, and it is clear that English readers are becoming more interested in literary and non-fiction works that have been written in different languages.

The rousing reception towards translated non-fiction work, like Thomas Piketty’s bestseller, Capital in the 21st Century (translated by Arthur Goldhammer), and literary works like this year’s Man Booker International winner, Han Kang’s The Vegetarian (translated by Deborah Smith), shows that translators are set to take on a more major role in the world of publishing.

To celebrate International Translation Day, which falls on 30 September every  year, we caught up with Frank Palmos, the acclaimed journalist, historian, and translator of works such as Bao Ninh’s award-winning The Sorrow of War, and more recently, Revolution in the City of Heroes, a first-hand account of Indonesian nationalists’ efforts to gain independence from the Dutch in Surabaya in 1945. Here, Dr Palmos shares his experience of translating and why translations are important for the preservation of memory and history.

year, we caught up with Frank Palmos, the acclaimed journalist, historian, and translator of works such as Bao Ninh’s award-winning The Sorrow of War, and more recently, Revolution in the City of Heroes, a first-hand account of Indonesian nationalists’ efforts to gain independence from the Dutch in Surabaya in 1945. Here, Dr Palmos shares his experience of translating and why translations are important for the preservation of memory and history.

Translators have been said to be literary activists, given that they play such a strong role in facilitating the travel of stories across borders of language. Can you tell us more about your experience in translating fiction (The Sorrow of War) and non-fiction (Revolution in the City of Heroes)?

The “borders” my languages had to cross borders were very local indeed. I was born in a tiny timber town in Central Victoria and schooled in a tiny one-roomed, six-class school of rarely more than 35 pupils, which was rated a hardship post for teachers, resulting in a rapid turnover of teachers and accents, from harsh Australian to middle-England or Northern Ireland.

My Irish-descended Australian-born mother, who spoke faultless, wonderfully clear English, married a Greek born man who never did master English (so he spoke with a Greek accent), and I learnt to both imitate and understand at a very early age. My neighbours were Scot-born, tough country folk whose harsh accents were also a good training for me. By the time I was ten years of age, I could entertain my classmates and certain adults by imitating all these accents.

The two books that you have translated deal with very heavy topics such as ideological battles and wars of independence. What draws you to translate stories like this?

I won a United Nations (UN) sponsored Fellowship in Djakarta (as it was known then) in 1961, administered by the Indonesian Foreign Office. Part of the reward was being able to live with Indonesian families of my choosing, which helped me learn about Indonesian people and their habits from early morning until late at night. I soon discovered almost every Indonesian spoke a regional language and Bahasa Indonesia, the national language. Hence I began to speak and mentally translate Sundanese as well as Indonesian when with my first family in Bandung.

I enjoyed listening to President Sukarno speak so much that I studied hard to attain a level that gave me confidence to request a position as an unofficial translator of President Sukarno’s annual August 17 Independence Day speeches. I was given the requisite passes to the Merdeka Palace and permission to hook up my headphones to an old National radio set.

President Sukarno (Source: Wikimedia Commons).

I was placed about 25 metres behind the president, facing away from him and towards the large assembly of diplomats and foreign press. I gave a passable simultaneous translation of his 1961 Independence Day speech. I hardly

remembered a word of it, but others said I got almost one half of the speech correct, without missing any important dot points. Sukarno often repeated his main points, which helped. Years later, my UN interpreter colleagues comforted me by saying they, too, hardly remembered any of their simultaneous translations. The brain switches itself into automatic translation gear.

I found that I liked doing that work and particularly enjoyed answering the telephone in my hosts’ Jakarta homes, successfully conversing without the callers knowing I was a foreigner, although once, Deputy Prime Minister Johannes Leimena called with a message for my host and upon ending the call, asked if my parents were Dutch. “I think I hear a little Dutch accent,” he said.

How has your background in journalism helped in translating?

The first reason I was comfortable writing the English Version of Bao Ninh’s book was that my original translator of my 1990 book, Ridding the Devils, Madame Hao, was a very reliable technical translator. The second reason was that I did not regard The Sorrow of War as fiction, nor frankly did Bao Ninh, although he had to clothe his stories in certain make belief vignettes. Ridding the Devils was non-fiction, so I wrote Sorrow of War using the same depth of knowledge gained on 33 land, sea and air missions, as a Vietnam War correspondent.

Usually, foreign correspondents do not learn the languages of the countries they report. It is one of the great failings that still exists throughout the western world today, where publishers rarely place correspondents abroad for more than three or four years and do not interest themselves in funding language training or cultural adaptation. I funded my own fare to Indonesia in the days when a flight to Djakarta was the equivalent to AUD $5,000 return today, on a BOAC Comet.

My interest in Indonesia began in 1961 and will continue until I die. I find no difficulty in retaining my love for Australia, Greece, France, and Singapore, for that matter, where I lived in the dramatic years during the formation (and partial break-up) of Malaysia. But as an historian, I find it my duty to repay the hospitality and friendship of the Indonesian people.

In the Sukarno years (1950–1965) research into the foundations of the Republic were not welcomed because the President felt that “nation building” was more important, and by nation building he meant that to keep the peace he did not wish to place greater credit on one ethnic group over another. The role of Surabaya and East Javanese was not accentuated, yet that was where the Republic finally won a small piece of territory for the fledgling Republic at a time when independence seemed an eventuality many years off.

I have used my research and translation skills and my past friendships with Indonesian leaders, many of whom were founders of the Republic, to write the complete history of the founding of the Republic in 1945. It was printed last week in Bahasa Indonesia, titled Surabaya 1945: Sakral Tanahku (Surabaya 1945: Sacred Territory).

Surabaya after the uprisings on 31 October 1945 (Source: Universities Kristen Petra; this photo is part of the collections at the Imperial War Museum).

However, Revolution in the City of Heroes—the Suhario Padmodiwiryo (alias "Hario Kecik") diary that is known as Student Soldiers in its original form in Bahasa Indonesia—is an important part of Indonesia’s history and of that Surabaya story. Unless I had worked with the author (General Suhario) until his death in December 2014, that history would have been lost. In years to come this generation of modern Indonesians will look back and be thankful that works like Kecik’s are in their National Archives.

Five Minutes with Nicholas Herriman September 23, 2016 15:00

If you thought witch-hunts were a thing of the 17th cenutry, think again.

In 1998, around 100 people were killed for being sorcerers in Banyuwangi, Indonesia. This figure far outnumbers the number of people who were executed during the Salem witch trials of 1692–1693, where 200 were put on trial and 20 were executed.

Nicholas Herriman, a senior lectuerer in Anthropology at La Trobe

University, set out to find out why the killings happened as part of research for his PhD thesis between 2000-2002. His findings and arguments about the Banyuwangi incident are presented in his latest book, Witch-Hunt and Conspiracy: The ‘Ninja Case’ in East Java. We caught up with Dr Herriman to talk about witch-hunts, why anthropology is an important discipline in the study of culture and society, and his interest in podcasts (and making them).

Were the sorcerer killings in Banyuwangi the first cases to pique your interest in witchcraft and magic?

Honestly, yes! Prior to learning about the killings, my interest in Indonesia had focused on cultural performance and literature. I first heard about the sorcerer killings in 1998. The killings troubled by me. I wondered, “How could there be a witch-hunt in modern times?” I also thought, “Who was behind the killings? Who benefitted from the killings?”

These questions, it turned out, were naïve and misplaced. But I asked myself these kinds of questions. Arriving in the field in 2000, I still assumed that the witch-hunt had nothing to do with magic, but was rather tied up with national political interests. While doing fieldwork (2000–2002), I began to realise that witchcraft and magic were crucial to understanding the killings. That was the first time my interest was piqued.

In Southeast Asia today, is the belief and practice of black magic and sorcery still very common?

As far as I can tell, belief in and practice of black magic and sorcery are very common. We could qualify that statement, as academics are wont to do, by questioning what we mean by “belief”, “practice”, “magic”, and “sorcery”. Nevertheless, studies from different parts of the region report on widespread suspicions. People suspect that their neighbour, colleague, rival, or whoever it might be draws on extraordinary or unseen powers for immoral ends. The people suspected are from the heights of power to the poorest and disenfranchised.

What were the challenges you faced during your field work in Banyuwangi when you undertook the task of conducting over 100 interviews for ethnographic research?

Professionally, the fieldwork was easy. People readily admitted to killing suspected sorcerers. Indeed, in some cases, they boasted and overstated their roles! By contrast, I struggled, personally. Initially I was horrified—I had to deal with ill health and exhaustion. I kept going primarily because I thought it was crucial to get an accurate historical record this massacre; especially as press and academic reports were so misleading. I wrote Witch-hunt and Conspiracy with this objective in mind.

This woman believed she had been ensorcelled. Her protruding stomach is visible from the profile. Dr Herriman is in the background. (Photo courtesy of L. Indrawati)

What are your thoughts about interdisciplinary studies? Upon reading your book, one can see that the historical and political contexts are very important to explaining how local dynamics or reactions to a situation came about (I.e., In your book, the context of 1998 being a period of Reformasi was very important in explaining how locals were reacting to political and social change after the fall of the Suharto government).

My feeling is that context is crucial in all studies of culture and society. Nevertheless, when I compare the anthropological approach with the interdisciplinary approach, I can discern differences in how to treat this context. Based on my fieldwork, the first book I wrote is called The Entangled State. I wrote this as an anthropologist. I was concerned with how the official treatment of the “problem of sorcery” in Banyuwangi could relate to anthropological theories about the state. I contended that the state was entangled in local communities. Because of this, I argued, senior bureaucrats are hamstrung in trying to contain the “problem of sorcery”.

Witch-hunt and Conspiracy is the second book I have written from my research on the sorcerer killings. I have focused closely on the killings themselves and attempted to understand them as an interplay between local dynamics and larger developments. I see this book as an interdisciplinary study in an area studies tradition. I like a diversity of approaches. The paradox of knowing the world is that each different understanding brings both insights and limitations. So I see pros and cons to both anthropological and interdisciplinary area studies.

So how did your academic background shape the way you approached the killings?

As a philosophy student I was introduced to the skepticism of David Hume and others. I was profoundly disturbed by questions about how we know what we think we know. Of course, I have no greater insight into these problems than most people. So the skeptical attitude remained with me. In research and writing Witch-hunt and Conspiracy, I continually challenged and questioned myself. In fact, after months and months of fieldwork the patterns of the killings began to seem clearer to me. I had begun to feel there was no conspiracy behind the killings. Yet I still did not trust appearances. So, for instance, when I interviewed people I would ask, “So who was behind the conspiracy?” Assuming that the truth remains hidden from me was my modus operandi in researching Witch-hunt and Conspiracy. I wanted, as much as possible, to be sure of my findings.

You are known as the “Audible Anthropologist”, having done a podcast series about anthropological concepts. What got you thinking about doing a podcast series as a way of promoting anthropology as a field of discipline and interest? And are you thinking of doing another season of podcasts, or a new series of podcasts?