News

Follow NUS Press on

Five Minutes with David Teh August 16, 2017 10:00

Earlier this year, David Teh published Thai Art: Currencies of the  Contemporary, which examines the transition of Thai contemporary art from a nationalist subjectivity to a postnational one. His analysis is set against the backdrop of the Thai monarchy’s waning sovereignty amidst political and economic turmoil.

Contemporary, which examines the transition of Thai contemporary art from a nationalist subjectivity to a postnational one. His analysis is set against the backdrop of the Thai monarchy’s waning sovereignty amidst political and economic turmoil.

In this edition of Five Minutes with…, Teh, an independent curator and Assistant Professor in the Department of English Language and Literature at the National University of Singapore, reveals how he first became involved in Thai contemporary art. He also shares how his curatorial experiences and intellectual inclinations have influenced his work, and the importance for Art History as a discipline to ‘decolonise’ itself.

What are the qualities of Thai contemporary art that drew you to study it, over other Southeast Asian nations with their own contemporary art?

I got to know about Thai contemporary art while living and working as a writer and curator in Bangkok. The book reflects that—I didn't go there looking to do academic research. That said, I already knew the Thai art scene was strong. Several Thais had built high profiles on the international exhibition circuit. But I was more curious about what was going on locally. As I got to know people, I learned about the burst of exciting, independent activity in the late 1990s—artists of my own generation were beneficiaries of that—but by the time I showed up, things had stagnated. The indie scene had run out of puff. The government was beginning to promote contemporary art but it was very tough for artists to make the work they wanted to make. So, I found I was most useful as an independent curator.

Tang Chang, Untitled, 1969, oil on canvas, 98 x 103 cm (Courtesy: Thip Sae-Tang/ Installation view. Image credit: Laura Fiorio / HKW)

It was never a choice between Thailand and other countries. I hadn't studied Southeast Asia or its history, and I got to know the region through the lens of Thailand, a place which—like Singapore—both belongs in the region and doesn't quite belong. Apart from their successes abroad, several things were distinctive about Thailand's artists. First, many were working confidently in non-traditional modes (eg. installation, video, conceptual art) even though those forms were not well supported by institutions or galleries. Second, there was often nothing very 'Thai' about their work, at least not visibly. This was in stark contrast with the art of the '90s, the bread and butter of the biennials sprouting in so many places. For me, national identity was a boring, hackneyed subject. And here was a generation of artists who weren't interested in national branding, yet who knew their cultural background would determine how their work was interpreted and valued. I found this tension fascinating, and it became a central concern of the book.

In the central chapters, you examine various forms of indigenous “currencies”—an agricultural symbology, a Siamese poetics of distance and itinerancy, and Hindu-Buddhist conceptions of charismatic power—and how contemporary art has converted them into other currencies. Why have you chosen to write about these particular forms of currency? Or, more specifically, what makes these very currencies the “national currencies” of Thai art?

The term 'currencies' is unorthodox in an art historical context. That discipline's habitual methods are failing: traditional, biographical approaches ended up in the bogus mythology of the singular creative genius; iconography charts the visible resemblances between one artist and another but in our networked, image-saturated environment, those patterns are unraveling; formalism imposes boundaries between various media that artists themselves no longer observe. In distilling some salient themes and concerns from Thai contemporary art, I was led by the artists I found most interesting. The challenge lay in figuring out how to historicise their work, and the 'currencies' I identified were a provisional solution, a way of tying artists and artworks into much larger social and cultural histories, while bypassing some of the pigeonholes of conventional art history. So, when contemporary artists adopt the theme of agriculture, for example, one might look back through eighty years of Thai modern art and find a few precedents. But agricultural imagery belongs to an ancient vocabulary of power in this part of the world, and it's more than just visual. That deeper, wider history illuminates today's art far more than recent art history can.

Similarly, Thai artists have attained social and intellectual cachet thanks to the patronage of the modern state and other institutions, but if you trace this 'charisma' within that institutional sphere, you only get half the story. For fifty years, the dominant 'national school'—the state academy (now Silpakorn University) set up in the 1930s—was the nerve centre through which all aesthetic traffic was routed, controlling access to resources and training, awarding coveted prizes and commissions, and setting artistic standards. Patronised by state and palace, Silpakorn was the main clearing house for artistic currencies, especially those stemming from the three institutional 'pillars' of Thai nationalism—religion, monarchy and nation. But since the 1980s ,its monopoly has crumbled: competing schools have been established, while globalisation has brought artists new sources of prestige and opportunity.

Near the entrance of Silapkorn University, which has served as the bastion of artistic pursuits in Thailand since the 1930s

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons).

What I call a 'currency' is a value an artist might intentionally rehearse—sometimes it's as simple as a visual cue, a choice of colours, a well-known symbol, a sign of the past or 'tradition'. But sometimes it's more abstract, or a projection onto their work by others. Some currencies are not visible, but are generated in the performance of being a modern artist. For instance, what does it mean to locate yourself in the provinces and address the orang kampung, using everyday materials and references, rather than the recognised idiom of 'fine art' from the national-institutional centre? This is a question that can be asked all over Southeast Asia. As we look beyond the obvious centres of production, there will be dozens of different answers, but also some overlaps and resonances.

I should stress that this book is by no means a comprehensive account—there are many currencies I haven't dealt with. I focused on the ones that have secured art's contemporaneity in Thailand, that is, those that qualify certain modern art as no longer simply modern, but 'contemporary'. International mobility was obviously a key currency, as it became more and more a fact of everyday professional life. But it also opens up new critical possibilities: when a work is shown in different places, it can carry different meanings and values. Artists are not naive about these differences; they exploit them, and the critic can examine this as a kind of arbitrage. It's no accident that the acceleration of Asian art's transnational exchange coincided with a regional financial crisis, sparked by the failure of the Thai baht in 1997.

How has your work as a critic and curator shaped how you approached your research for this book?

This is a crucial dimension of the book. From a traditional disciplinary standpoint it will seem methodologically unresolved, for it brings together all sorts of knowledge: plenty of historical (but not exactly 'art historical') context; critical responses to seeing exhibitions; and lengthy conversations with artists and curators that might be called 'ethnographic', though again, collected in somewhat heuristic and undisciplined ways. These are exactly the data sets of curatorial work, and Art History has been slow to take advantage of them. Making exhibitions, one develops a great reservoir of trust with artists and others who know and care about art. There's an intimacy you don't get from looking at catalogues—you learn things that can't be learned any other way.

In the West, Art History has ceded a lot of ground to various kinds of 'visual studies', and there's a burgeoning literature on histories of exhibition and curatorship. But in Southeast Asia, Art History is still getting clumsily on its feet. Universities have largely failed to seize an obvious opportunity. Meanwhile museums are going up with breathtaking speed, but without the necessary software to make them relevant. Until recently, research wasn't part of the curatorial skill set in Singapore, which is clearly the region's institutional centre of gravity. I think I'm very lucky that I found publishers who understood this patchy landscape, and that independent curators have been a crucial link in the knowledge chain. It's an imperfect science, to be sure, but ten or twenty years from now I think the book's idiosyncrasies, and its deficiencies, will tell us something about this moment.

Pratchaya Phinthong, Who Will Guard the Guards Themselves?, 2015. Lightbox, duratrans, and steel frame; 161 × 200 × 9 cm. Collection of Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (Courtesy of the artist and gb agency, Paris).

In the book, you challenged Singapore-born artist Jay Koh’s condescending response to Thai-born artist Rirkrit Tiravanija’s simulacrum of his New York apartment—titled “Tomorrow Is Another Day”—at the Kölnischer Museum, and contended with the view that representing one’s national polity of origin lies at the heart of the artistic enterprise. In your opinion, why is there a prevalence of this biased attitude towards national identification in the transnational sphere?

Its prevalence today may be put down to laziness, to certain ingrained habits of artists, writers and exhibition-makers. But there are clear historical reasons for it. In the late 1980s, contemporary art began to circulate transnationally with a new intensity, a whole new scale of exchange. There's a pair of excellent books on this moment, put out by Afterall under the title Making Art Global. One can pin this to the thaw of the Cold War and a certain narrative of globalisation, though upon close examination in a given place, one finds very complex processes at work. Nevertheless, this circuit became the basis of the transnational art system we see today. With this burst of circulation, audiences—particularly professional ones—came face to face with art from other worlds, from social, historical and aesthetic contexts about which they were often perfectly ignorant. Identity (and not exclusively national identity) was the primary interpretive crutch, providing a way in, some starting point for the uninitiated viewer confronted with Vietnamese, Peruvian, or Congolese contemporary art for the first time.

Southeast Asia's artists are still subject to the gravity of nation, much more than their counterparts in the Euro-American sphere whose institutions still dominate the art economy. In fact, when I travel in that post-national milieu, I'm the one insisting that the nation still matters! But as an interpretive support, it can only be one amongst many. Some artists still make art about national identity and belonging, either because those things are still material to their lives, or because they're on auto-pilot—it's what Southeast Asian art has done for twenty years; it's what made their mentors famous. But for most young artists in the region, national heritage and national problems are no longer front-of-mind. We have to find other ways of understanding their work and what it has to tell us, including what it might say about the place where it was made.

You recently curated an exhibition in Berlin, titled "Misfits". Are there any overarching ideas that you always try to put into your work, be it in curation or in writing?

David Teh introducing “‘Misfits’: Pages from a loose-leaf modernity” to visitors at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (Photo credits: Laura Fiorio / HKW).

I'm a card-carrying anti-essentialist. Most of my work is about unpicking and sabotaging big, overarching ideas. "‘Misfits’: Pages from a loose-leaf modernity" is about the process of canon formation that has been accelerated by the museum boom, and the recent discovery of Southeast Asia by first-world collecting institutions. I chose three modern artists on the cusp of canonisation, whose legacies haven't been mediated by national institutions, either because they deliberately kept their distance from the latter, or because the latter's narratives simply couldn't accommodate them. Two of them died in 1990: the Burmese artist and illustrator, Bagyi Aung Soe, and the Sino-Thai modernist Tang Chang. The third was Rox Lee, a Filipino filmmaker who is still very much alive and kicking. This grouping is unorthodox, but I liked how it opened up the question of what distinguishes 'modern' from 'contemporary'. (This is also a preoccupation of my book.) A growing curatorial workforce is busily constructing an overarching idea of 'Southeast Asian modern art'. It's important that we complicate the picture, and to that end, these 'misfits' are important circuit-breakers.

What sort of future conversations do you hope that this book will inspire?

In the broader (global) context, I think Art History is an ossified discipline, badly in need of renewal. Its academic mainstream is still cloistered, in Europe and North America; its conceptual toolkit is inadequate for the task of decentering and decolonising the history of modern art. Serious efforts are being made to adopt a more inclusive outlook—sometimes framed as 'world art history'—but encyclopaedic surveys only get you so far, and they don't make for compelling reading. To make Art History relevant again, its methods need to be deconstructed, its vocabularies need to be hacked. And we have to devise interdisciplinary but historically rigorous ways of furnishing context.

Closer to home, I hope the book's strengths and weaknesses will be picked apart and will provoke more critical discussion. It's a very charged environment in Thailand at the moment. The generals have their fingers in the dyke but the tide of history is pressing in. Managing a sensitive royal succession, the dictatorship has shut down the system of political expression; there's no public sphere, and criticism has become more and more dangerous. But at the same time, the country is gradually awakening from a long bout of historical naivety; people are reading more and debating more than they have for decades, largely thanks to the advent of social media. Thai artists are not known for taking strident political positions, yet the art world can be a relatively accommodating place for public discourse and argument, often flying beneath the radar of officialdom. I hope the book will be a conversation starter. Each chapter, each theme, is intended to open new ways of understanding contemporary art, and the social realities and histories it reflects.

NUS Press at ICAS 2017 July 28, 2017 17:16

NUS Press participated in the 2017 International Convention of Asia Scholars conference at Chiang Mai Convention Centre in Chiang Mai, Thailand last week (July 20-23).

Organised by the Regional Center for Social Science and Sustainable Development (RCSD), with support from the Faculty of Social Sciences of Chiang Mai University, we were pleased to participate at the conference's Asian Studies book fair.

(Photo credit: Valerie Yeo)

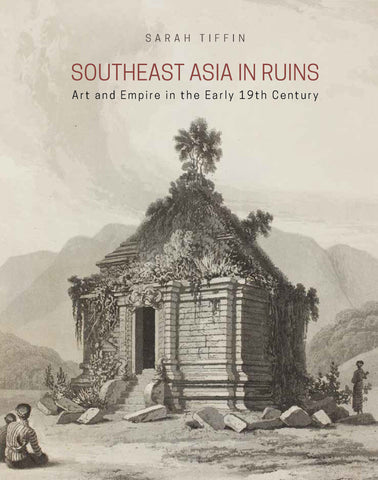

We were also pleased that Sarah Tiffin's Southeast Asia in Ruins: Art and Empire in the Early 19th Century was shortlisted for the ICAS Book Award. Whilst it did not win, we were pleased with the overwhelming interest in the book and our art history publishing programme.

Here are highlights of some of the books that were displayed:

- Liberalism Disavowed: Communitarianism and State Capitalism in Singapore by Chua Beng Huat

- US-Singapore Relations, 1965-1975: Strategic Non-alignment in the Cold War by Daniel Wei Boon Chua

- Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary by David Teh

- Sovereignty and the Sea: How Indonesia Became an Archipelagic State by John Butcher and R. E. Elson

- The ASEAN Miracle: A Catalyst for Peace by Kishore Mahbubani and Jeffery Sng

- Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia [NEW JOURNAL]

The 11th edition of ICAS will take place in Leiden, the Netherlands (July 16-19, 2019). For updates on ICAS-11, please check the ICAS website occasionally at the following link: http://icas.asia/en/icas11

Five Minutes with Southeast of Now March 24, 2017 11:00

This month marks the official launch of Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, a new journal devoted to art in Southeast Asia (and the wider region). The journal's inaugural issue has been launched at several events across Southeast Asia, engaging scholarly as well as artistic and curatorial publics.

This month marks the official launch of Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, a new journal devoted to art in Southeast Asia (and the wider region). The journal's inaugural issue has been launched at several events across Southeast Asia, engaging scholarly as well as artistic and curatorial publics.

In January, the journal had a soft launch that coincided with the Singapore Biennale Symposium at the National Museum of Singapore, and an informal launch was held earlier this month at the Jim Thompson Art Center in Bangkok to coincide with the exhibition People, Money, Ghosts (Movement as Metaphor).

In this edition of Five Minutes with …, we caught up with the editorial collective—Isabel Ching, Thanavi Chotpradit, Brigitta Isabella, Eileen Legaspi-Ramirez, Yvonne Low, Vera Mey, Roger Nelson, Simon Soon, and Vuth Lyno—to discuss the complexities of an exisiting “gap” about contemporary art in Southeast Asia, the decision to have a thematic focus of “discomfort”, and what readers can expect in future issues of Southeast of Now.

In the editorial to this inaugural issue of Southeast of Now, you express a desire to address a gap in current scholarship about contemporary art in Southeast Asia. Could you briefly account for the nature and complexities of this gap? Why aren’t enough people writing about contemporary art in the region and, even so, why aren’t writers framing their research “historically”?

Yvonne Low: Saying that there is a gap in current scholarship about contemporary art in Southeast Asia does not mean that there aren’t any writings on and about the contemporary; on the contrary, there are a lot. Such writings however are frequently curatorially driven or biennially-driven (if such a term maybe used). In some instances, such as in Indonesia, writings on contemporary art are commissioned by collectors. For all these reasons, research and writing on contemporary art in Southeast Asia are often skewed toward particular collections, personal or public; they may be responding to particular themes or have had to meet particular objectives. With the exception of the rare few publications (for example,T. K Sabapathy's Intersecting Histories: Contemporary Turns in Southeast Asian Art) that make a serious attempt to look at the region’s contemporary art historically, mapping commonalities and shared pasts, and identifying intersections and inter-/intra-regional developments, the far more common approach taken of contemporary is to view it as ahistorical, an artistic phenomenon that does not have any precedence, when this is clearly not true. And especially not when conditions that led to the rise of contemporary art in the region was traceable to as early as the seventies.

The First Southeast Asia Art Competition Exhibition, Manila, 12 May 1957

(Courtesy of Vanessa Ban. Original Source can be found in the MoMA Archives, New York IC/IP I.A.408)

You settled on “Discomfort” as the theme for the first Call For Papers. What sort of provocations did you hope to invite?

Editorial Collective: To adapt the words used in the Call For Papers and the editorial from the inaugural issue, the provocations that the Southeast of Now editorial collective wanted to invite were pieces that reflect on the burdens and future possibility of wielding “regionalism” as a framework. The playful disquiet evoked by the title of the journal, which troubles linear notions of space-time and destablises any certainty of an imagined temporal centre, gave rise to the first theme. “Discomfort” locates this source of tension and anxiety as a productive register to explore various discursive stakes, propelled by new urgencies, orientations, and motivations; and perhaps discover therein some comfort, even if merely within shared discomfort.

Image from Sharmini Pereira with P. Kirubalini, “Searching for Discomfort” (an essay from the inaugural issue of Southeast of Now)

Alongside traditional academic writing, the Artists’ Projects section in this issue features fascinating work by artists such as Shooshie Sulaiman, who is based in Kuala Lumpur, and a transcribed conversation between artist Tom Nicholson, curator Grace Samboh and the late Edhi Sunarso, who was supposedly “Sukarno’s most trusted sculptor”. How do you see this section evolving as a space for creating discourses about contemporary Southeast Asian art? What, in your opinion, are the curatorial possibilities here?

Vera Mey: It was important for us to create an open platform within the journal where we could pair artistic responses to the various journal themes we have planned. We also wanted to have the possibility for an artistic response which could be purely visual alongside more scholarly articles and written work. A lot of contemporary artists are engaged in artistic research and have different ways of demonstrating this beyond writing an article, essay or review. In the case of the transcript in the video work by Tom Nicholson with Grace Samboh we also wanted a place where this kind of research material, in this case generated from an interview of a video work, could travel beyond the site of the physical exhibition in which it was originally viewed, which was the Jakarta Biennale. Within the context of the journal it is not only an artwork to be experienced; it is also a primary source of research material about an aspect of Indonesia's art history.

There are endless curatorial possibilities here. The artists' pages could be a space for a specifically curated space of images or texts either by a member of the editorial collective, a guest curator, or someone with a desire to respond to our call for proposals. This follows new approaches to publishing where printed matter is considered equally an exhibitionary format in two-dimensional form. In future issues we will also alternate between archival pages from various archives within and beyond the region and the artists’ pages.

With the opening of National Gallery Singapore in 2015 and the upcoming opening of Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Nusantara (Museum MCAN) in Jakarta, it appears as if substantial investments, whether from public institutions or private individuals, are being channeled to the area of contemporary art. Where do you think a journal of critical scholarship such as Southeast of Now might fit, given its context?

Brigitta Isabella: The infrastructure of public and private institutions in Southeast Asia cannot be generalized as having similar nature and agendas. Its characters are contingent on the context of relationship between artists, curators, the state and the market inside the local art scene. Within this context, there are different power plays shaped by politics of nationalism, commercialization of art and commodification of culture, as well as narratives of resilience from minor artists and alternative spaces that also greatly contribute to the practice of contemporary art. Framing an apt critique of art institution in the region certainly cannot follow the discourse of institutional critique within the Western art system and here the journal is trying to present a necessarily historical perspective to understand the shifting cultural context in Southeast Asia. Another fact to consider is the lack of educational infrastructure of art history in most countries in Southeast Asia, so, in a way, the journal serves as a trans-local container and a discursive space for creating encounters between critical scholarships of contemporary and modern art produced in, from and around the region.

What other conversations do you foresee happening within the pages of future volumes of Southeast of Now?

Roger Nelson: The categories of “contemporary and modern art,” indeed of “art” in general, are obviously terms we consider to be open for debate just as much as the category of “Southeast Asia” itself. Given this, we anticipate continuing to trouble and denaturalise these categories, including through looking at aspects of culture that don't usually qualify as “art,” and also through treating the region's borders as fluid, and looking at research that transcend these borders.

But in all this, we remain committed to the importance of an historical approach, however interwoven with methodologies from other disciplines and practices that historical approach might also be. We would be delighted if future issues of the journal can look further back in time, to the 19th century (and before), and perhaps can place this historical research in dialogue with issues of today (and the future).

To find out more about submission guidelines and subscription information, visit www.southeastofnow.com or the NUS Press Southeast of Now page.

Five Minutes with Sarah Tiffin February 10, 2017 09:00

When Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles published his landmark book The History of Java  in 1817, ruins were far more than the architectural detritus of a former age. Images of ruins reminded people of the transience of human achievements, and stimulated broader philosophical enquiries into the rise and decline of entire empires. In this edition of Five Minutes with ..., we speak with Sarah Tiffin, author of Southeast Asia in Ruins: Art and Empire in the Early 19th Century, who shares with us how art history has become a useful source to understanding colonialism and why portrayals of the "Other" will continue to pique public imaginations.

in 1817, ruins were far more than the architectural detritus of a former age. Images of ruins reminded people of the transience of human achievements, and stimulated broader philosophical enquiries into the rise and decline of entire empires. In this edition of Five Minutes with ..., we speak with Sarah Tiffin, author of Southeast Asia in Ruins: Art and Empire in the Early 19th Century, who shares with us how art history has become a useful source to understanding colonialism and why portrayals of the "Other" will continue to pique public imaginations.

Colonial art seems undervalued/understudied as a resource that could potentially yield insights into colonial perspectives and preoccupations; why do you think this is so?

Actually, I think a great deal of really interesting and thought provoking work has been done on colonial art, particularly by art historians responding to the ideas initially raised by Edward Said and the ensuing debates surrounding his work. Certainly, their work has had an influence on my own. But I think that in the area I am interested in— the work of British artists in Southeast Asia—there is room for a great deal more scholarship. So often in discussions of British art and empire, the work of British artists in Southeast Asia is overlooked. I think the dominance of India in British imperial thinking and experience has had a big part in this, and it is understandable given the huge quantity of materials that were produced as a result of British rule in India. But there is also a wealth of fascinating material relating to the British in Southeast Asia that could generate some really interesting new scholarship.

A painting by William Daniell titled, ‘The large temple at Brambánan’, from T.S. Raffles, The History of Java, Vol. 2 (London: 1817)

(Image courtesy of The Fryer Library, University of Queensland Library)

Your previous book was about the depiction of Chinese poets by a Japanese artist in the seventeenth century. Have you always been intrigued by the politics of representation behind the portrayals of a culture by others?

Do you know, I hadn’t really thought about that connection before as the starting points for my books were very different. My first book was produced for a small art exhibition that was based around a pair of Japanese screens—it explored the iconography of the screens within the context of 17th century Japan. Southeast Asia in Ruins, on the other hand, grew out of a doctoral dissertation and my studies in Southeast Asian history as well as my interest in British art. What I am particularly interested in is socio-political context, in how art reflects the society in which it is created and at the same time, it also influences that society.

In Southeast Asia in Ruins, you explore how the British saw the ruined candi as evidence of a cultural, and indeed civilisational, decline of Southeast Asian peoples. Did the British apply this line of thinking to their other colonies, or were such notions particular to the Southeast Asian region?

The linking ruins, or images of ruins, with ideas about cultural decline was an essential part of late 18th and early 19th century ruin appreciation. The remains of the past allowed people to derive a melancholic pleasure from contemplating the transience of even the most grandiose of humankind’s deeds and designs, including the demise of entire empires. For British ruin enthusiasts, the fall of civilisation was most throughly associated with Rome—most famously in Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire—but this thinking was also extended to the remains of past civilisations in other parts of the world. The British response to Southeast Asia’s ruins, then, was not a unique one, but part of a wider expression of ruin sentiment.

A painting by William Daniell titled ‘Prome, from the heights occupied by His Majesty’s 13th Light Infantry’, from James Kershaw, Views in the Burman Empire (London, 1831)

(Image courtesy of The Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection)

What piqued your interest in images of Southeast Asian ruins that were idealised popular colonial British imagination?

When I first looked at Raffles’ The History of Java, I was struck by the beauty of Daniell’s aquatint ruin plates. I was familiar with the images of Indian architecture he and his uncle Thomas had created for the superb Oriental Scenery, but I had not seen his images of the Javanese remains before and I felt they really deserved more attention. Similarly, the engraved vignettes by a number of British printmakers that are scattered throughout Raffles’s text are really lovely and very fascinating, yet I found very little had been published on them, or on the wealth of archaeological drawings now held in the collections of the British Library, the British Museum and the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. It has been something of a labour of love, and I hope it might encourage other people to look at these wonderful collections for their own research projects.

William Daniell, A Javan in the court dress (plate from The History of Java by Thomas Stamford Raffles, London : 1817, vol. 1), coloured antiquint

(Image courtesy of the Fryer Library, University of Queensland Library)

What is your next project? Will you return to the museum/gallery scene?

I am currently working on a study of Southeast Asia in 17th century English poetry, prose, pageantry and drama, looking at how authors responded to the aspirations and experiences of English merchants then active in the region, and the changing political and economic imperatives at home and abroad. I’m keen to keep working on this project over the next couple of years, but apart from that, I’m not sure what the future holds!

Sarah Tiffin

(Image provided by Dr Tiffin)

Soft Launch of Southeast of Now at the National Museum of Singapore January 26, 2017 09:00

In conjunction with the Singapore Biennale 2016 Symposium, NUS Press’s newest journal dedicated to art history in the region—Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia—was launched at the National Museum of Singapore’s Gallery Theatre last Sunday (22 January).

(Image credit: Pallavi Narayan)

A panel that included renowned art historians John Clark, Patrick D. Flores and T.K. Sabapathy, NUS Press Director Peter Schoppert, as well as two members of the Southeast of Now editorial collective Simon Soon and Yvonne Low, discussed the significance of producing an academic journal dedicated to contemporary art in the region.

Left to right: Yvonne Low, Simon Soon, T.K. Sabapathy, John Clark, Patrick D. Flores

and Peter Schoppert

(Image credit: Sebastian Song)

John Clark, Emeritus Professor in the Department of Art History at the University of Sydney, opened the session with remarks about the role of journals in forming and sustaining epistemic communities. He spoke on Southeast of Now’s potential to engage “laterally” with other clusters of research within the general field of art history and contemporary arts scholarship, and praised the “chutzpah of young art historians in the field,” citing this as evidence of a thriving community of researchers.

(Image credit: Sebastian Song)

Thereafter, T.K. Sabapathy, a leading authority on art history in Singapore and Malaysia, considered the role of publishers and university presses in fostering an environment conducive to research: “NUS Press,” he rejoined half-jokingly, “has woken up.”

Patrick D. Flores, Curator of the Vargas Museum, Manila, and a professor with the Department of Art Studies at the University of the Philippines, suggested that the journal represents a new development in the professionalization of arts research. He added that the journal also provides young arts researchers invaluable opportunities for acknowledging the “different system of knowledge-making in the region.”

(Image credit: Sebastian Song)

Peter Schoppert elaborated on the series of decisions that led to NUS Press’s acquisition of the journal. According to him, the editorial collective’s energy levels, commitment and openness were “impressive,” and, interestingly, their proposals were also accompanied by “rumours” of their ambition and ability spread by their teachers, supervisors and mentors. To end the panel, he quoted extensively from an interview—included in the first issue of the journal—with Stanley J. O’Connor, on the idea that in the face of global upheaval and changes in the production and practice of art, “nothing can be more important than the decentering of the art world,” a process which is “by no means automatic.”

(Image credit: Sebastian Song)

Southeast of Now will be published twice a year (March and October). Register with Project MUSE to enjoy free previews of Vol. 1, No. 1 (March 2017) and Vol. 2, No. 2 (October 2017). For editorial enquiries, contact the editors at southeastofnow@gmail.com. Click here to find out more subscription rates and to subscribe to the journal.