News

Follow NUS Press on

Five Minutes with Samuel Ling Wei Chan May 15, 2019 09:42

I n April this year, Dr Samuel Ling Wei Chan published "Aristocracy of Armed Talent, The Military Elite in Singapore". It explores the Singapore Armed Forces by a comprehensive and in-depth examination of its elite leadership: the 170 men (and a very few women) who served or serve as flag officers, that is generals or admirals. How did Singapore build a culture of leadership for its armed forces? What role did the SAF Scholars scheme, introduced in 1971, play in forming this culture?For this edition of Five Minutes With... we turned to noted military expert and journalist David Boey, who conducted this interview and first ran it on his excellent blog on Singapore military matters, Senang Diri. Thanks to David for the interview and for giving us permission to run it on the website.

n April this year, Dr Samuel Ling Wei Chan published "Aristocracy of Armed Talent, The Military Elite in Singapore". It explores the Singapore Armed Forces by a comprehensive and in-depth examination of its elite leadership: the 170 men (and a very few women) who served or serve as flag officers, that is generals or admirals. How did Singapore build a culture of leadership for its armed forces? What role did the SAF Scholars scheme, introduced in 1971, play in forming this culture?For this edition of Five Minutes With... we turned to noted military expert and journalist David Boey, who conducted this interview and first ran it on his excellent blog on Singapore military matters, Senang Diri. Thanks to David for the interview and for giving us permission to run it on the website.

How long did it take you to write the book?

The book is a revised and updated edition of my PhD thesis. I started my studies in March 2011 but by February 2012 it was apparent that my initial topic (on military education in Australia and the US) was not tenable.

What made you press on with research on the SAF despite initial hurdles?

It was a challenge to complete a puzzle and I was focused on the task at hand. The topic is interesting to me, both in academic and general terms.

What was the most challenging aspect of the research for this book?

The most challenging aspects were access to information in terms of open source material and interviews for the specific questions that I had in mind.

How did you go about resolving the challenge(s)?

The 28 interviews were great and a blessing in terms of being able to get the work done.

Which chapter did you enjoy researching/writing most?

I must say I enjoyed them all due to the variation, focus, and information in each of the chapters.

What are the takeaways you hope the reader will glean from the book?

To appreciate the SAF in its entirety, both the good, the quirky, and the not so good.

NUS Press at ICAS 2017 July 28, 2017 17:16

NUS Press participated in the 2017 International Convention of Asia Scholars conference at Chiang Mai Convention Centre in Chiang Mai, Thailand last week (July 20-23).

Organised by the Regional Center for Social Science and Sustainable Development (RCSD), with support from the Faculty of Social Sciences of Chiang Mai University, we were pleased to participate at the conference's Asian Studies book fair.

(Photo credit: Valerie Yeo)

We were also pleased that Sarah Tiffin's Southeast Asia in Ruins: Art and Empire in the Early 19th Century was shortlisted for the ICAS Book Award. Whilst it did not win, we were pleased with the overwhelming interest in the book and our art history publishing programme.

Here are highlights of some of the books that were displayed:

- Liberalism Disavowed: Communitarianism and State Capitalism in Singapore by Chua Beng Huat

- US-Singapore Relations, 1965-1975: Strategic Non-alignment in the Cold War by Daniel Wei Boon Chua

- Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary by David Teh

- Sovereignty and the Sea: How Indonesia Became an Archipelagic State by John Butcher and R. E. Elson

- The ASEAN Miracle: A Catalyst for Peace by Kishore Mahbubani and Jeffery Sng

- Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia [NEW JOURNAL]

The 11th edition of ICAS will take place in Leiden, the Netherlands (July 16-19, 2019). For updates on ICAS-11, please check the ICAS website occasionally at the following link: http://icas.asia/en/icas11

Five Minutes with Lisandro E. Claudio July 18, 2017 15:30

In March earlier this year, Lisandro E. Claudio published Liberalism  and the Postcolony: Thinking the State in 20th-Century Philippines. Prior to this groundbreaking work, historical scholarship on liberalism in the Philippines was largely unexplored. In this edition of Five Minutes With…, we chat with Claudio—an Associate Professor of History at Manila’s De La Salle University more affectionately known as Leloy—about how his book was born, his experience of writing in Kyoto, free dinners, politics, and his revolutionary of a grandmother.

and the Postcolony: Thinking the State in 20th-Century Philippines. Prior to this groundbreaking work, historical scholarship on liberalism in the Philippines was largely unexplored. In this edition of Five Minutes With…, we chat with Claudio—an Associate Professor of History at Manila’s De La Salle University more affectionately known as Leloy—about how his book was born, his experience of writing in Kyoto, free dinners, politics, and his revolutionary of a grandmother.

Although your book is concerned with Philippine politics and intellectual history, it was written during a two-year postdoctoral fellowship in Kyoto. How did that distance help shape your critical views?

I’ll use this question as an opportunity to thank my host institution. The Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS) at Kyoto University was the perfect place to write a book on a Southeast Asian state. For one, it is close enough to allow regular trips back to the region. So, in a sense, I actually did not have much distance. What I had was time to think and write amid the monastic yet urban atmosphere of Kyoto, while being able to easily book a flight to the Philippines if I needed to plug gaps in the research.

Secondly, CSEAS does Southeast Asian Studies for Southeast Asians. Its sensei have solid connections with the region, and they have a clear idea of their audience. My primary audience has been and will always be Filipinos, who think about and debate the future of our political community. Kyoto reinforced this. It is not a place that forces you to get into an academic rat race, where you aim to publish with American publishers while jumping on the latest American trend (whatever that may be—I think it’s affect theory at the moment). I’d like to think that because of the culture of CSEAS, I produced a book for Filipinos and Southeast Asians, written without paying obeisance to trends in cultural theory. And because I was in Kyoto, I was encouraged to publish in the premier academic press in Southeast Asia (that’s you guys!), and co-publish with the premier academic press in the Philippines (Ateneo de Manila University Press). If people outside my intended audiences wish to pick up the book because they are interested in liberalism, of course, that would make me happy. They can buy something from Singapore or Manila. But the primary goal is to talk to Filipinos concerned about the Philippines qua state.

Japan is wonderful because, like the US, it has money for research, but without the trendiness. And this was a very square, untrendy book about a philosophical idea that is not as exciting and revolutionary as postcolonial theory or even good ole’ Marxism. Moreover, if I were in the US, I might have had to factor identity politics into the manuscript, since Filipinos there are almost obligated to ‘interrogate’ or ‘problematize’ their subjectivities. But in Japan, you do what you want. So I wrote a book that conceived of “Filipino” as a political community as opposed to cultural identity. I wanted to write a book about civic nationalism/patriotism, unabashedly anchored on conceptions of the state.

Finally, Kyoto provided me the best mentorship. I sped through my PhD in three years in Australia, and felt a bit ‘undercooked’ at the end of it—not because my teachers failed to guide me, but simply because I was in such a rush to complete the degree (I was homesick in the beginning). Writing this book felt like writing a second dissertation. In the process, I benefited greatly from CSEAS’ Caroline S. Hau, who made me think about the relationship between liberalism and our vague notions of who the ‘elite’ are (while buying me multiple dinners). She also made me, almost against my will, think about liberalism and macroeconomics, which produced the chapter on Salvador Araneta. I owe so much to Carol for gently nudging me out of my comfort zone.

The nationalist economist Salvador Araneta pictured with family at Far East Air Transport, Incorporated, n.d. (Image credit: Manila Times Photo Archive, Rizal Library, Ateneo de Manila University).

You mention in your book’s introduction that you are interested in “bureaucratic writers and pencil-pushers, who aided the transition of a nation from colonial rule to independence” over other groups with nation-building interests. What attracted you to these particular perspectives of liberalism and postcolonialism?

As I said earlier, I’m attracted to, for lack of a better term, squareness. This is why a section of the introduction is called “a defense of boring politics.” Why must academic work have to be sexy or provocative? Especially when the topic is a postcolonial society like the Philippines. My sense is that, since academics like me are square personalities anyway, we should also write about square topics, like, yes, the history of pencil-pushers. Come on, how many academics are really revolutionaries? And yet some of them write like they’ll be the next Che Guevara. I’m only being slightly facetious here.

In Southeast Asian studies, we’ve been so obsessed with insurgencies, millenarian movements, anarchism, mythological and magical interpretations of politics, et cetera. I almost feel like there is an element of self-Orientalization. Maybe we should also talk about reason and Enlightenment and not be ashamed of it.

I think there is a need to grapple with Southeast Asian modernities that are in dialogue with Western Enlightenment. Unearthing the history of the Philippine liberal tradition was my way of doing this. I have a number of friends in Thai studies who are doing similar things, looking at Thai liberalism. I hope we can push the limits of Southeast Asian studies and write more histories of square people.

You also observe that, in Filipino history, liberalism is often excluded from the records despite its close ties to Philippine nationalism. How did you come into this insight and what was the first step you took in addressing this exclusion?

Yes, look at our national hero José Rizal, for example. With perhaps the exception of John N. Schumacher and Nick Joaquin, very few writers talk about him as a liberal. Always a nationalist, but never a liberal. But he was so obviously a liberal! The guy was perennially talking about the rights of man and the need to defend liberty. He even wrote numerous essays against the absolute power created by martial law (how proto-anti-Marcos, right?).

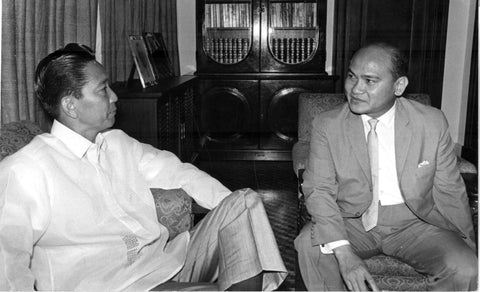

Former president Ferdinand Marcos (left), who ruled the Philippines from 1965 to 1986, meeting the educator and statesman Salvador P. Lopez, n.d. (Image credit: Manila Times Photo Archive, Rizal Library, Ateneo de Manila University).

I don’t remember exactly how I came to my insight about the exclusion of liberalism from the national narrative. But I do remember my other mentor, Patricio Abinales, once asking me—way before I decided to write this book—why nobody had written a history of Philippine liberalism. I guess I never got that question out of my head. So I ended up working on this book.

Maybe the exclusion of the liberal tradition comes from the fact that much of our country’s liberalism is of American vintage (although, as I mentioned earlier, Rizal’s generation was already liberal). In the 1970s, Philippine historiography fell prey to a rabid, almost ethnocentric nationalism that dismissed anything from the US or the West as external to the Philippine experience, and that included liberalism. It had a very insidious effect, and the rhetoric survives today, mouthed, no less, by our dictatorial baby boomer president, Rodrigo Duterte.

You know what makes my blood boil? When Filipino politicians, especially supporters of the president, say Filipinos should challenge “Western liberalism.” As if liberalism were so external to our national experience.

How do we go beyond the exclusion of liberalism? I’m very practical about this. Perhaps we should stop obsessing about the provenance of an idea. Instead, maybe we should ask if an idea, regardless of where it comes from, is a good one. In the book, I tried to make the case that liberalism is a good idea for the Philippines, especially during the age of what commentators have called “Dutertismo.”

What were the major obstacles you faced in sourcing material for your book?

Nothing much. The advantage of intellectual history is that you work largely with published material. The most difficult chapter to research was the one on Salvador P. Lopez, because he lacked vanity. The rest of the intellectuals in the book loved to self-publish their speeches, but SP was too self-effacing (unlike his hucksterish, but formidable, mentor, Carlos P. Romulo) to play that game. With the help of my friend Aaron Mallari, I was able to dig through the SP Lopez papers in the University of the Philippines Diliman. It’s a treasure trove, actually. More people should go there—if they can take the heat and the dust.

SP Lopez addressing students, teachers, and staff during the Diliman Commune of February 7, 1971. (Image credit: Manila Times Photo Archive, Rizal Library, Ateneo de Manila University)

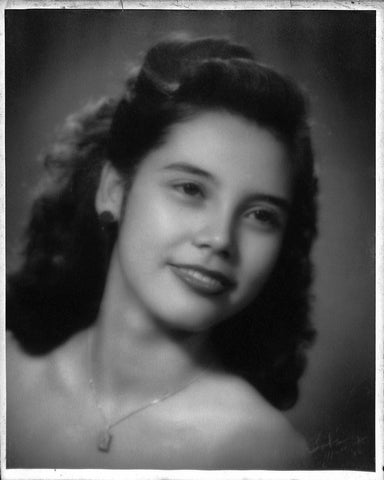

In your afterword, you offer a fifth liberal to join the four historical protagonists in your book—your maternal grandmother, Rita D. Estrada, who had been a professor at the University of the Philippines. Based on your tender and illuminating portrait of her, she was a remarkably charming and extraordinary woman. Would you consider writing a book on her one day?

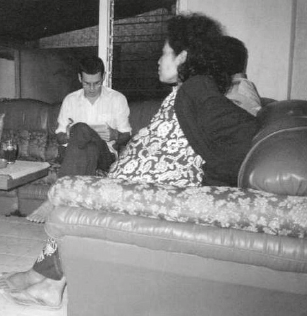

Rita D. Estrada, the author’s grandmother and a revolutionary liberal in her own right. (Image credit: Lisandro E. Claudio)

Thank you, I tried to conjure the Lola Rita of my memories, while representing her as an intellectual in her own right.

But, no, I don’t think I'd be able to write a full book about her. There isn’t enough material. My lola was a quiet intellectual who did not leave behind a lot of writings. The epilogue of the book is enough of a tribute to her, and enough naval-gazing for me. I enjoyed writing it, though, and it made my mom cry.

Five Minutes with Andrea Benvenuti June 21, 2017 12:00

With the recent publication of his new book, Cold War and Decolonisation: Australia’s Policy towards Britain’s End of Empire in Southeast Asia, Andrea Benvenuti seeks to challenge popular views—and misconceptions—of Australian relations with its neighbouring region during the Cold War. Moreover, Benvenuti, a senior lecturer in International Relations and European Studies at the University of New South Wales, offers a fresh and incisive look at the Australian perspective during the emergence of independent Southeast Asian nations and the collapse of British colonial rule.

With the recent publication of his new book, Cold War and Decolonisation: Australia’s Policy towards Britain’s End of Empire in Southeast Asia, Andrea Benvenuti seeks to challenge popular views—and misconceptions—of Australian relations with its neighbouring region during the Cold War. Moreover, Benvenuti, a senior lecturer in International Relations and European Studies at the University of New South Wales, offers a fresh and incisive look at the Australian perspective during the emergence of independent Southeast Asian nations and the collapse of British colonial rule.

In this edition of Five Minutes With …, Dr Benvenuti debunks the myths surrounding Australian political history, particularly those regarding the Menzies government, transplants his Cold War observations into the current political climate, and shares his upcoming projects.

What attracted you to the Australian policy perspective of the Cold War?

One of the enduring myths in Australian political history is that Australia failed to pursue an independent foreign policy in Asia during the early Cold War. As the story goes, under the Liberal–Country Party Coalition government of Sir Robert Menzies (1949–66) Australia overplayed the threat of international communism and became closely aligned with the United States and Britain in an effort to contain the spread of communism in Asia. However, by identifying itself too closely with American and British Cold War policies in Asia, the Menzies government, it is said, foreclosed any chance of engaging meaningfully with its neighbouring region and of developing a distinctive regional role for Australia. The underlying assumption here is that Australia would probably have been better off pursuing a neutralist foreign policy.

Robert Menzies (left) meets with US Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara at the Pentagon in 1964

(Image credit: Wikimedia Commons).

I have never been persuaded by these kinds of arguments and I thought I ought to find out more. I hope my book will provide a less distorted appreciation of Australia’s Cold War role in Asia and thus make a significant contribution to a better understanding of Australian policy concerns and interests, in a region of paramount strategic, political and economic importance.

What insights does your book offer on Australian foreign policy and relations with Southeast Asia that other historians may have neglected?

Another enduring myth in Australian history and politics is the idea that the Menzies years stand as a blot on the relationship between Australia and Southeast Asia. In Australian universities, scores of undergraduate and postgraduate students are taught to believe that Menzies’ conservative government had little interest in forging close and enduring links with Southeast Asia. According to the prevailing academic wisdom (one that is often embraced with gusto by the Australian media), Menzies’ Anglophilia and his keenness to nurture close ties with Australia’s ‘great and powerful friends’ (the US and Britain) prevented Australia from developing closer regional ties. Only with the arrival of Gough Whitlam at The Lodge (the Australian Prime Minister’s residence in Canberra) in 1972 did Australia begin to seriously engage with the region.

Nothing, of course, could be farther from the truth and my book shows just how grotesque this view is. Under Menzies, Australia pursued a policy of active and sustained regional engagement. Southeast Asia’s political stability and economic prosperity were of utmost importance to Menzies’ Australia, and the Liberal–Country Party government acted accordingly by placing regional engagement at the forefront of its foreign policy.

A clip of Gough Whitlam’s 1974 visit to the Philippines, which was part of a Southeast Asian tour to strengthen ties between the region and Australia. Whitlam also visited Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Laos, and Burma. (Source: Whitlam Institute YouTube Channel; footage courtesy of the National Film and Sound Archive and the National Archives of Australia [NAA 4423/31]).

The Menzies government expressed approval of Malaya and Singapore’s bids for merger and independence from British rule. How has this endorsement shaped Australia’s relations with Malaysia and Singapore since the Cold War era?

It has no doubt contributed to drawing Australia closer to Malaysia and Singapore, and forging an enduring and deep relationship with them.

In light of increasing nationalism amongst certain world powers, what lessons on navigating security and international relations from your book might be applicable today?

It is often difficult to compare the world of the 1950s or 1960s with our own. When I talk to my undergraduate students about the early Cold War years in Southeast Asia, I sometimes feel as if I am talking to them about ancient history, given that so much has changed at international and regional levels since then. With this proviso in mind, I venture to offer one possible lesson: as the history of modern Singapore and Malaysia clearly shows, regional political stability and economic prosperity are best maintained through a continuing and robust Western engagement with the region and vice-versa. Beijing’s version of ‘Asia for the Asians’ is really in no one’s interest.

What are your current research projects?

I am currently working on two projects: the first deals with Western (American, British and Australian) responses to the emergence of non-alignment in Asia during the 1950s and early 1960s. The second examines the role and impact of Western military power and strategic foreign policy in the ordering and re-ordering of Asia between 1919 and 1989. It is a collaborative international project sponsored by the Department of History at the National University of Singapore and led by Professor Brian Farrell.

Five Minutes with Southeast of Now March 24, 2017 11:00

This month marks the official launch of Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, a new journal devoted to art in Southeast Asia (and the wider region). The journal's inaugural issue has been launched at several events across Southeast Asia, engaging scholarly as well as artistic and curatorial publics.

This month marks the official launch of Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, a new journal devoted to art in Southeast Asia (and the wider region). The journal's inaugural issue has been launched at several events across Southeast Asia, engaging scholarly as well as artistic and curatorial publics.

In January, the journal had a soft launch that coincided with the Singapore Biennale Symposium at the National Museum of Singapore, and an informal launch was held earlier this month at the Jim Thompson Art Center in Bangkok to coincide with the exhibition People, Money, Ghosts (Movement as Metaphor).

In this edition of Five Minutes with …, we caught up with the editorial collective—Isabel Ching, Thanavi Chotpradit, Brigitta Isabella, Eileen Legaspi-Ramirez, Yvonne Low, Vera Mey, Roger Nelson, Simon Soon, and Vuth Lyno—to discuss the complexities of an exisiting “gap” about contemporary art in Southeast Asia, the decision to have a thematic focus of “discomfort”, and what readers can expect in future issues of Southeast of Now.

In the editorial to this inaugural issue of Southeast of Now, you express a desire to address a gap in current scholarship about contemporary art in Southeast Asia. Could you briefly account for the nature and complexities of this gap? Why aren’t enough people writing about contemporary art in the region and, even so, why aren’t writers framing their research “historically”?

Yvonne Low: Saying that there is a gap in current scholarship about contemporary art in Southeast Asia does not mean that there aren’t any writings on and about the contemporary; on the contrary, there are a lot. Such writings however are frequently curatorially driven or biennially-driven (if such a term maybe used). In some instances, such as in Indonesia, writings on contemporary art are commissioned by collectors. For all these reasons, research and writing on contemporary art in Southeast Asia are often skewed toward particular collections, personal or public; they may be responding to particular themes or have had to meet particular objectives. With the exception of the rare few publications (for example,T. K Sabapathy's Intersecting Histories: Contemporary Turns in Southeast Asian Art) that make a serious attempt to look at the region’s contemporary art historically, mapping commonalities and shared pasts, and identifying intersections and inter-/intra-regional developments, the far more common approach taken of contemporary is to view it as ahistorical, an artistic phenomenon that does not have any precedence, when this is clearly not true. And especially not when conditions that led to the rise of contemporary art in the region was traceable to as early as the seventies.

The First Southeast Asia Art Competition Exhibition, Manila, 12 May 1957

(Courtesy of Vanessa Ban. Original Source can be found in the MoMA Archives, New York IC/IP I.A.408)

You settled on “Discomfort” as the theme for the first Call For Papers. What sort of provocations did you hope to invite?

Editorial Collective: To adapt the words used in the Call For Papers and the editorial from the inaugural issue, the provocations that the Southeast of Now editorial collective wanted to invite were pieces that reflect on the burdens and future possibility of wielding “regionalism” as a framework. The playful disquiet evoked by the title of the journal, which troubles linear notions of space-time and destablises any certainty of an imagined temporal centre, gave rise to the first theme. “Discomfort” locates this source of tension and anxiety as a productive register to explore various discursive stakes, propelled by new urgencies, orientations, and motivations; and perhaps discover therein some comfort, even if merely within shared discomfort.

Image from Sharmini Pereira with P. Kirubalini, “Searching for Discomfort” (an essay from the inaugural issue of Southeast of Now)

Alongside traditional academic writing, the Artists’ Projects section in this issue features fascinating work by artists such as Shooshie Sulaiman, who is based in Kuala Lumpur, and a transcribed conversation between artist Tom Nicholson, curator Grace Samboh and the late Edhi Sunarso, who was supposedly “Sukarno’s most trusted sculptor”. How do you see this section evolving as a space for creating discourses about contemporary Southeast Asian art? What, in your opinion, are the curatorial possibilities here?

Vera Mey: It was important for us to create an open platform within the journal where we could pair artistic responses to the various journal themes we have planned. We also wanted to have the possibility for an artistic response which could be purely visual alongside more scholarly articles and written work. A lot of contemporary artists are engaged in artistic research and have different ways of demonstrating this beyond writing an article, essay or review. In the case of the transcript in the video work by Tom Nicholson with Grace Samboh we also wanted a place where this kind of research material, in this case generated from an interview of a video work, could travel beyond the site of the physical exhibition in which it was originally viewed, which was the Jakarta Biennale. Within the context of the journal it is not only an artwork to be experienced; it is also a primary source of research material about an aspect of Indonesia's art history.

There are endless curatorial possibilities here. The artists' pages could be a space for a specifically curated space of images or texts either by a member of the editorial collective, a guest curator, or someone with a desire to respond to our call for proposals. This follows new approaches to publishing where printed matter is considered equally an exhibitionary format in two-dimensional form. In future issues we will also alternate between archival pages from various archives within and beyond the region and the artists’ pages.

With the opening of National Gallery Singapore in 2015 and the upcoming opening of Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Nusantara (Museum MCAN) in Jakarta, it appears as if substantial investments, whether from public institutions or private individuals, are being channeled to the area of contemporary art. Where do you think a journal of critical scholarship such as Southeast of Now might fit, given its context?

Brigitta Isabella: The infrastructure of public and private institutions in Southeast Asia cannot be generalized as having similar nature and agendas. Its characters are contingent on the context of relationship between artists, curators, the state and the market inside the local art scene. Within this context, there are different power plays shaped by politics of nationalism, commercialization of art and commodification of culture, as well as narratives of resilience from minor artists and alternative spaces that also greatly contribute to the practice of contemporary art. Framing an apt critique of art institution in the region certainly cannot follow the discourse of institutional critique within the Western art system and here the journal is trying to present a necessarily historical perspective to understand the shifting cultural context in Southeast Asia. Another fact to consider is the lack of educational infrastructure of art history in most countries in Southeast Asia, so, in a way, the journal serves as a trans-local container and a discursive space for creating encounters between critical scholarships of contemporary and modern art produced in, from and around the region.

What other conversations do you foresee happening within the pages of future volumes of Southeast of Now?

Roger Nelson: The categories of “contemporary and modern art,” indeed of “art” in general, are obviously terms we consider to be open for debate just as much as the category of “Southeast Asia” itself. Given this, we anticipate continuing to trouble and denaturalise these categories, including through looking at aspects of culture that don't usually qualify as “art,” and also through treating the region's borders as fluid, and looking at research that transcend these borders.

But in all this, we remain committed to the importance of an historical approach, however interwoven with methodologies from other disciplines and practices that historical approach might also be. We would be delighted if future issues of the journal can look further back in time, to the 19th century (and before), and perhaps can place this historical research in dialogue with issues of today (and the future).

To find out more about submission guidelines and subscription information, visit www.southeastofnow.com or the NUS Press Southeast of Now page.

Five Minutes with Ronald McCrum February 24, 2017 10:00

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the Fall of Singapore. Considered one of the greatest defeats in the history of the British Army during World War Two, retired British Army Officer and military historian, Ronald McCrum, undertakes a close examination of the role and the responsibilities of the colonial authorities in his new book, The Men Who Lost Singapore, 1938-1942.

Considered one of the greatest defeats in the history of the British Army during World War Two, retired British Army Officer and military historian, Ronald McCrum, undertakes a close examination of the role and the responsibilities of the colonial authorities in his new book, The Men Who Lost Singapore, 1938-1942.

In this edition of Five Minutes With ..., we talk to Colonel McCrum to get his insights on how his military background helped his research, his history and ties with Southeast Asia, and whether co-ordination between civil authorities and military bodies has improved nearly eight decades on.

How did you come to be interested in the military history of this particular region?

My interest in military history was, I suppose, inevitable. At 18 years of age, I decided to become a soldier and at Sandhurst, the officer training college, part of the curriculum is military history and it fascinated me. In any case, it was now my chosen profession and I almost felt duty bound to understand something of the trials and tribulations of my predecessors.

The Far East, Malaya/Malaysia and Singapore were of particular interest because I spent a lot of my life in these parts. I first came to the area not long after the end of the war (1948/49?)—my father was then stationed in Nee Soon. We lived just outside Johor Bahru and I went to ‘English College’ in Johor Bahru. After a period in England, we returned to Malaya, this time to Kuala Lumpur (KL) and I went to Victoria Institution in KL. So the formative years of my life were in this part of the world.

McCrum in Germany (Iserlohn), 1981

(Image credit: Ronald McCrum)

In your book you discuss the various factors leading up to Singapore’s downfall, particularly how the preparation and execution of British defence strategies were addled by the conflicting views, interests and priorities of the military and civil authorities. In what ways has your military experience allowed you to be more attuned to these issues?

In 1965, after I had been a commissioned officer in the British Army for a number of years, an opportunity arose to be seconded for a period to the Malaysia Armed Forces and I accepted. I was sent to the Malaysian Military College at Sungei Besi just outside KL as an instructor. While in Malaysia my first two sons were born, the first shortly after we arrived and the second just before we returned to UK. And then surprisingly in 1970 after completing a year’s course at the British senior officers Staff College I was sent to Singapore as the Assistant Defence Advisor to the British High Commissioner. Where I spent two and half very happy years and my third and last son was born there. All three boys have Southeast Asia in their blood.

You’ve pointed out the civil authorities were slow to recognise the impending threat of the Japanese invasion. Was this general across other European colonies in Southeast Asia, or was it particular to Singapore? Do you think issues of co-ordination between civil authorities and military bodies improved with the advent of new technologies and procedures of co-ordination today?

While in Malaysia/Singapore I was endlessly curious about how the British Forces were so easily beaten in 1941/42. And in my travels I took the chance to visit the scenes of the battles that took place. After much reading, I began to recognise that in those early days of a new form of mobile modern warfare no one escaped an enveloping invasion. Inclusive lessons of total war were quickly learnt in the West, but in the quiet backwater of South East Asia such a prospect seemed remote. Glaringly obvious afterwards was the need for a combined (civil and military) planning headquarters, with an overall supremo able to impose decisions. At that time the three military services had each their own HQ’s in different locations in Singapore and the Governor was remote in Government House. Now of course a combined planning authority is normal greatly helped, of course, by modern communications. I cannot think of a current example where the civil and military authorities do not work closely together towards a common aim. A good instance in the Far East, after the war, was the combined operations of all the authorities in Malaya planning the defeat of the communist terrorists during the Malayan Emergency.

McCrum in Israel, 1988

(Image credit: Ronald McCrum)

What also struck me as grossly negligent was the poor, indeed almost non-existent, liaison between the Colonial Office and the War Office in London. One was demanding increased production of tin and rubber and the other telling the military they had to employ local labour to prepare defences. The same labour that was required on the rubber estates and the tin mines. There were of course a number of other very important factors that played a crucial part in the defeat, but the authorities quarrelling on basic matters like this did not help.

What are your future plans? Are you thinking of writing another book?

I am well into researching another book. This time a biography of a significant British figure who played an important part during the Indian Mutiny of 1857.

McCrum in Singapore with an advance copy of

The Men Who Lost Singapore in early February 2017

(Image credit: Pallavi Narayan)

Five Minutes with Sarah Tiffin February 10, 2017 09:00

When Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles published his landmark book The History of Java  in 1817, ruins were far more than the architectural detritus of a former age. Images of ruins reminded people of the transience of human achievements, and stimulated broader philosophical enquiries into the rise and decline of entire empires. In this edition of Five Minutes with ..., we speak with Sarah Tiffin, author of Southeast Asia in Ruins: Art and Empire in the Early 19th Century, who shares with us how art history has become a useful source to understanding colonialism and why portrayals of the "Other" will continue to pique public imaginations.

in 1817, ruins were far more than the architectural detritus of a former age. Images of ruins reminded people of the transience of human achievements, and stimulated broader philosophical enquiries into the rise and decline of entire empires. In this edition of Five Minutes with ..., we speak with Sarah Tiffin, author of Southeast Asia in Ruins: Art and Empire in the Early 19th Century, who shares with us how art history has become a useful source to understanding colonialism and why portrayals of the "Other" will continue to pique public imaginations.

Colonial art seems undervalued/understudied as a resource that could potentially yield insights into colonial perspectives and preoccupations; why do you think this is so?

Actually, I think a great deal of really interesting and thought provoking work has been done on colonial art, particularly by art historians responding to the ideas initially raised by Edward Said and the ensuing debates surrounding his work. Certainly, their work has had an influence on my own. But I think that in the area I am interested in— the work of British artists in Southeast Asia—there is room for a great deal more scholarship. So often in discussions of British art and empire, the work of British artists in Southeast Asia is overlooked. I think the dominance of India in British imperial thinking and experience has had a big part in this, and it is understandable given the huge quantity of materials that were produced as a result of British rule in India. But there is also a wealth of fascinating material relating to the British in Southeast Asia that could generate some really interesting new scholarship.

A painting by William Daniell titled, ‘The large temple at Brambánan’, from T.S. Raffles, The History of Java, Vol. 2 (London: 1817)

(Image courtesy of The Fryer Library, University of Queensland Library)

Your previous book was about the depiction of Chinese poets by a Japanese artist in the seventeenth century. Have you always been intrigued by the politics of representation behind the portrayals of a culture by others?

Do you know, I hadn’t really thought about that connection before as the starting points for my books were very different. My first book was produced for a small art exhibition that was based around a pair of Japanese screens—it explored the iconography of the screens within the context of 17th century Japan. Southeast Asia in Ruins, on the other hand, grew out of a doctoral dissertation and my studies in Southeast Asian history as well as my interest in British art. What I am particularly interested in is socio-political context, in how art reflects the society in which it is created and at the same time, it also influences that society.

In Southeast Asia in Ruins, you explore how the British saw the ruined candi as evidence of a cultural, and indeed civilisational, decline of Southeast Asian peoples. Did the British apply this line of thinking to their other colonies, or were such notions particular to the Southeast Asian region?

The linking ruins, or images of ruins, with ideas about cultural decline was an essential part of late 18th and early 19th century ruin appreciation. The remains of the past allowed people to derive a melancholic pleasure from contemplating the transience of even the most grandiose of humankind’s deeds and designs, including the demise of entire empires. For British ruin enthusiasts, the fall of civilisation was most throughly associated with Rome—most famously in Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire—but this thinking was also extended to the remains of past civilisations in other parts of the world. The British response to Southeast Asia’s ruins, then, was not a unique one, but part of a wider expression of ruin sentiment.

A painting by William Daniell titled ‘Prome, from the heights occupied by His Majesty’s 13th Light Infantry’, from James Kershaw, Views in the Burman Empire (London, 1831)

(Image courtesy of The Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection)

What piqued your interest in images of Southeast Asian ruins that were idealised popular colonial British imagination?

When I first looked at Raffles’ The History of Java, I was struck by the beauty of Daniell’s aquatint ruin plates. I was familiar with the images of Indian architecture he and his uncle Thomas had created for the superb Oriental Scenery, but I had not seen his images of the Javanese remains before and I felt they really deserved more attention. Similarly, the engraved vignettes by a number of British printmakers that are scattered throughout Raffles’s text are really lovely and very fascinating, yet I found very little had been published on them, or on the wealth of archaeological drawings now held in the collections of the British Library, the British Museum and the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. It has been something of a labour of love, and I hope it might encourage other people to look at these wonderful collections for their own research projects.

William Daniell, A Javan in the court dress (plate from The History of Java by Thomas Stamford Raffles, London : 1817, vol. 1), coloured antiquint

(Image courtesy of the Fryer Library, University of Queensland Library)

What is your next project? Will you return to the museum/gallery scene?

I am currently working on a study of Southeast Asia in 17th century English poetry, prose, pageantry and drama, looking at how authors responded to the aspirations and experiences of English merchants then active in the region, and the changing political and economic imperatives at home and abroad. I’m keen to keep working on this project over the next couple of years, but apart from that, I’m not sure what the future holds!

Sarah Tiffin

(Image provided by Dr Tiffin)

Soft Launch of Southeast of Now at the National Museum of Singapore January 26, 2017 09:00

In conjunction with the Singapore Biennale 2016 Symposium, NUS Press’s newest journal dedicated to art history in the region—Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia—was launched at the National Museum of Singapore’s Gallery Theatre last Sunday (22 January).

(Image credit: Pallavi Narayan)

A panel that included renowned art historians John Clark, Patrick D. Flores and T.K. Sabapathy, NUS Press Director Peter Schoppert, as well as two members of the Southeast of Now editorial collective Simon Soon and Yvonne Low, discussed the significance of producing an academic journal dedicated to contemporary art in the region.

Left to right: Yvonne Low, Simon Soon, T.K. Sabapathy, John Clark, Patrick D. Flores

and Peter Schoppert

(Image credit: Sebastian Song)

John Clark, Emeritus Professor in the Department of Art History at the University of Sydney, opened the session with remarks about the role of journals in forming and sustaining epistemic communities. He spoke on Southeast of Now’s potential to engage “laterally” with other clusters of research within the general field of art history and contemporary arts scholarship, and praised the “chutzpah of young art historians in the field,” citing this as evidence of a thriving community of researchers.

(Image credit: Sebastian Song)

Thereafter, T.K. Sabapathy, a leading authority on art history in Singapore and Malaysia, considered the role of publishers and university presses in fostering an environment conducive to research: “NUS Press,” he rejoined half-jokingly, “has woken up.”

Patrick D. Flores, Curator of the Vargas Museum, Manila, and a professor with the Department of Art Studies at the University of the Philippines, suggested that the journal represents a new development in the professionalization of arts research. He added that the journal also provides young arts researchers invaluable opportunities for acknowledging the “different system of knowledge-making in the region.”

(Image credit: Sebastian Song)

Peter Schoppert elaborated on the series of decisions that led to NUS Press’s acquisition of the journal. According to him, the editorial collective’s energy levels, commitment and openness were “impressive,” and, interestingly, their proposals were also accompanied by “rumours” of their ambition and ability spread by their teachers, supervisors and mentors. To end the panel, he quoted extensively from an interview—included in the first issue of the journal—with Stanley J. O’Connor, on the idea that in the face of global upheaval and changes in the production and practice of art, “nothing can be more important than the decentering of the art world,” a process which is “by no means automatic.”

(Image credit: Sebastian Song)

Southeast of Now will be published twice a year (March and October). Register with Project MUSE to enjoy free previews of Vol. 1, No. 1 (March 2017) and Vol. 2, No. 2 (October 2017). For editorial enquiries, contact the editors at southeastofnow@gmail.com. Click here to find out more subscription rates and to subscribe to the journal.

NUS Press Highlights of 2016 December 27, 2016 10:30

While 2016 has proven to be a rather bleak and tumultuous year, we are proud to have published some books that will continue to have much bearing in the new year ahead.

ENVIRONMENT

All eyes will continue to be on Indonesia’s Peatland Restoration Agency as it implements plans of restoring peatland to prevent haze crises (like that of 2015) from engulfing the region again.

Two NUS Press books, Catastrophe and Regeneration in Indonesia’s Peatlands (edited by Kosuke Mizuno, Motoko S. Fujita and Shuichi Kawai) and The Oil Palm Complex (edited by Rob Cramb and John McCarthy) touched on some agricultural and labour challenges that Malaysia and Indonesia are facing within the oil palm industry and peatland agriculture. In his review of both books in The Jakarta Post, James Erbaugh commented that both titles “provide scholarship that elucidates the complexities of oil palm production, and the challenges presented by peatland agriculture as well as peatland restoration.”

POLITICS

Indonesia’s gubernatorial election is set to take place in February 2017 and Edward Aspinall’s and Mada Sukmajati’s edited volume, Electoral Dynamics in Indonesia will be handy for observers as it provides greater insight into the patronage systems and money politics at the grassroots level.

In the field of maritime developments: Tensions in the South China Sea will continue to have much bearing on US-China and China-ASEAN relations in 2017. Ng Chin-keong’s collection of essays, Boundaries and Beyond, provides a novel way of understanding the nature of maritime China, and the undercurrent of social and economic forces that have created new boundaries between China and the rest of the world.

Lastly, in light of the 29th Southeast Asian Games taking place in Kuala Lumpur next year, Stephen Huebner’s Pan-Asian Sports and the Emergence of Modern Asia, 1913-1974 explores the role international sporting competitions had in shaping discourses of nationalism and development across Asian states. As one of the first major studies of the history of sports in Asia, Dr Huebner’s book provides a compelling window into the intersection between sports and politics in the region.

SINGAPORE HISTORY

The history of pre-independence Singapore remained a staple to our publishing programme this year, with Timothy Barnard’s Nature’s Colony shedding much light on the Singapore Botanic Gardens' lively history. Professor Barnard examined the Gardens’ changing role in a developing Singapore—from colonial times under the charge of several colourful Superintendents and Directors, to today, as a World Heritage Site.

On a more personal level, social work pioneer Ann Wee reminisces about her eventful life in Singapore. Her memoir A Tiger Remembers ruminates on the Singaporean family, and presents the reader with a series of charming vignettes from her life that captures the nuanced transformation of Singaporean society over the years. These intimate recollections, all told in exquisite detail and rich with insight, are testament to the vibrant cultural heritage of the nation.

We are also proud to have published Professor Kenneth Dean and Dr Hue Guan Thye's two-volume set, Chinese Epigraphy in Singapore, 1819-1911, which has been described by Claudine Salmon, Director of Research Emeritus at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), Paris to be a "a repository of Singapore cultural and historical heritage." The collation of over 1,300 epigraphic records is a breakthrough in the telling of the Singapore story and according to Prof Dean, "such inscriptions provide snippets of what life was like in 19th and early 20th century Singapore, and capture the diverse cross-section of society at that time."

SOUTHEAST ASIAN ART HISTORY

What importance does art hold in the representation of history?

In the context of the portrayal of Southeast Asia by its colonial masters, Sarah Tiffin’s Southeast Asia in Ruins explores how the British justified colonialism through imperial art. Dr Tiffin will be speaking at the National Gallery Singapore on 25 February 2017 about British artists' portrayal of Southeast Asian civilization(s) in ruins in Stamford Raffles' The History of Java, and the role that these artists (and their work) played in Britain’s imperial ambitions in Southeast Asia.

In 2017, photographers and photojournalists will continue to play a vital role in exposing the realities of an increasingly authoritarian Southeast Asia. Zhuang Wubin’s Photography in Southeast Asia will be a useful introduction to the discourse of photographic practices in the region as his survey provides insights into the role images play in shaping Southeast Asian society, culture and politics.

Five Minutes with Brian Bernards November 22, 2016 15:00

In this special edition of our author-interview series, Professor Philip Holden from the National University of Singapore conducted an email interview with Professor Brian Bernards on the occasion of the publication of the Southeast Asian edition of Writing the South Seas: Imagining the Nanyang in Chinese and Southeast Asian Postcolonial Literature. An assistant professor at the University of Southern California, Bernards works in three languages – English, Chinese, and Thai—and his book thus gives a revisionary perspective on the literatures of the region, and indeed the way in which we imagine Southeast Asia itself.

University of Singapore conducted an email interview with Professor Brian Bernards on the occasion of the publication of the Southeast Asian edition of Writing the South Seas: Imagining the Nanyang in Chinese and Southeast Asian Postcolonial Literature. An assistant professor at the University of Southern California, Bernards works in three languages – English, Chinese, and Thai—and his book thus gives a revisionary perspective on the literatures of the region, and indeed the way in which we imagine Southeast Asia itself.

Professor Holden's and Professor Bernards' exchange was first published on singaporepoetry.com. We are pleased to present some excerpts of their lively discussions:

Philip Holden: As someone who has been studying auto/biography, I’m always interested in the life stories of scholars. What drew you to study Chinese and Thai? And what fostered your interest in the literatures of Southeast Asia?

Brian Bernards: When I was 9 years old, a family from Shanghai (a father, mother, and their 2-year-old daughter) moved in with my family at our home in Minneapolis. The father was studying engineering at the University of Minnesota, and the mother, who later went on to study accounting, became our live-in babysitter. On occasion, our two families had meals together, and the boiled dumplings (shui jiao) our sitter cooked became quickly my new favorite dish. Our good friends from Shanghai lived with us for about two years, when the father graduated and found a plush job in Milwaukee. Starting high school about three years later in 1992, I opted to take Mandarin because of my prior exposure to Chinese culture (and cuisine!). I first traveled to mainland China in 1998, where I studied for a year at Sichuan University in Chengdu. My language professor recommended Chengdu because she had done research there, she knew I wanted to tread beyond the typical path of studying in Beijing, Shanghai, or Taipei, and, most importantly, she knew I would like the spicy ma-la food there. Living and attending school in Chengdu certainly opened my eyes, and my taste buds, to new experiences, flavors, and possibilities.

PH: Given your exposure to different disciplines, what are your thoughts on inter-disciplinary studies?

BB: I have always enjoyed literature (especially fiction and poetry), music, and film. As a student and traveler, I felt I could better connect with a place, a culture, a society, and its history through the very personal stories and creative imagination conveyed in fiction and memoirs by authors who were from or who were very familiar with that society. While Southeast Asian studies in the US is largely a social science-oriented field, I was fortunate to take history and anthropology classes as an undergraduate from professors who, rather than assigning dry textbook readings, assigned novels by authors such as Pramoedya Ananta Toer, José Rizal, Duong Thu Huong, Ma Ma Lay, and Kukrit Pramoj, to be read in conjunction with course lectures. I was very inspired by this approach to history and cultural studies, not only because it put the human impact of historical events and social transformations in relatable narratives rather than abstract figures, but also because the micro-histories we encountered in such literary narratives often challenged or even contradicted the standard interpretations and “big picture” perspectives taken for granted in the official histories. I am grateful to my teachers for cultivating the approach that would stick with me as I moved forward into graduate studies.

PH: What was the process of writing Writing the South Seas like?

BB: Writing the South Seas began as a way of combining my interests and background knowledge in modern Chinese literature, Southeast Asian studies, and postcolonial literary theory in an attempt to make a novel contribution, and hopefully a type of critical intervention, in each field. I felt the varying approaches from these different fields could be mutually illuminating in ways that the disciplines had yet to sufficiently consider. Mainly, I sought to bring a Southeast Asia-centered perspective to the study of literatures in Chinese on and from the region. Luckily, I conceived the project at the time that Sinophone studies was emerging and bringing about a sea-change in the modern Chinese literary field. Sinophone studies not only emphasizes cultural networks across national and ethnic boundaries, but also seeks to situate such networks locally in their multilingual milieu. In this sense, my interests in Anglophone literature and Thai-language literature from Southeast Asia, which might have otherwise been seen as irrelevant or marginal to modern Chinese literary studies, could provide an insightful comparative perspective that showcased the cross-lingual interactions and relationships of these Sinophone literary networks. I owe a significant intellectual debt to the pioneering work of Shih Shu-mei in this regard.

PH: The cover of your book will have a particular resonance for many Malaysians and Singaporeans. Could you explain this?

BB: I really have you to thank for this, Prof Holden, as you were the first person to recommend Suchen Christine Lim’s novel Fistful of Colours to me when I began researching Anglophone authors in Singapore. As you know, at the end of the novel, the protagonist returns to Kuala Jelai, her home village in Malaysia, from Singapore, and she becomes moved viewing the large wall murals while waiting for her train at the Tanjong Pagar Railway Station. When I read this passage, I wanted to see the murals myself, though at the time I had no idea they would later provide the source material for the cover of my book.

That was before the station closed. When it was operational, the station, along with the Keretapi Tanah Melayu (KTM) railway tracks, was an important living legacy of the intimate relationship, common colonial history, and shared culture between the two countries. Now that it is closed, it can only serve as a “heritage site” – a relic or a reminder of that past. For a lot of Malaysians and Singaporeans who grew up when the two societies were more integrated, Tanjong Pagar is bound to be a source of nostalgia, especially because it conjures a more rustic landscape and older colonial architecture that contrasts with the image of Singapore as a city of glistening skyscrapers and squeaky-clean air-conditioned malls. I think this nostalgic sentiment regarding the railway station is quite obvious in “Parting,” director Boo Junfeng’s contribution to the omnibus film, 7 Letters: he uses the space of Tanjong Pagar to tell the story of an interethnic romance against the backdrop of racial riots in the 1960s.

Interior of Tanjong Pagar Railway Station, 2010

(Image credit: Jacklee, Wikimedia Commons)

Of the six triptych murals in the station, the one with the commercial maritime focus showing the harbour was the most relevant to my book in its entirety, so I commissioned an image of that mural for the cover. The different types of ocean vessels in the image, from a sampan to a junk to a passenger steamship, really captured the varying modes of maritime crossings and convergences that the Nanyang has historically signified. And it’s beautifully done.

****

NUS Press would like to thank singaporepoetry.com's founding editor, Koh Jee Leong for granting permission to republish these excerpts.

Launch of "Photography in Southeast Asia" in Singapore October 18, 2016 17:00

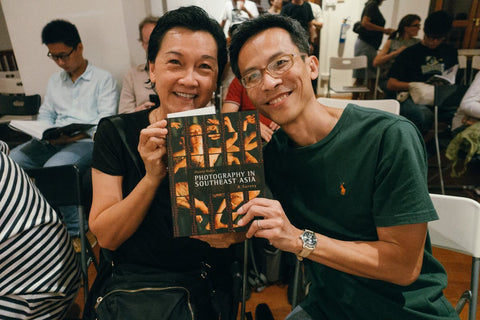

Zhuang Wubin's Photography in Southeast Asia: A Survey was launched at Objectifs Centre for Photography and Film on October 13, 2016. The launch featured a dialogue between Zhuang and famed street photographer, Chia Aik Beng, followed by a lively question and answer session.

(Photo courtesy of Kevin Lee)

Zhuang and Chia discussed the influence and impact social media has had on photography. When asked by Zhuang about the advantages and disadvantages of using Instagram as a platform for showcasing work, Chia said, "Instagram is a social media platform; it is not a photo gallery or website. If I'm on a project, I will share some images [on my Instagram account], to tease people and then direct them to my website. This is how I distribute information."

For a detailed transcript of what was discussed during the book launch, you can read Invisible Photographer Asia's coverage of it here. We are grateful to Objectifs for sponsoring the venue for this book launch, and to Kevin Lee for being the official photographer of the event.

Five Minutes with Nicholas Herriman September 23, 2016 15:00

If you thought witch-hunts were a thing of the 17th cenutry, think again.

In 1998, around 100 people were killed for being sorcerers in Banyuwangi, Indonesia. This figure far outnumbers the number of people who were executed during the Salem witch trials of 1692–1693, where 200 were put on trial and 20 were executed.

Nicholas Herriman, a senior lectuerer in Anthropology at La Trobe

University, set out to find out why the killings happened as part of research for his PhD thesis between 2000-2002. His findings and arguments about the Banyuwangi incident are presented in his latest book, Witch-Hunt and Conspiracy: The ‘Ninja Case’ in East Java. We caught up with Dr Herriman to talk about witch-hunts, why anthropology is an important discipline in the study of culture and society, and his interest in podcasts (and making them).

Were the sorcerer killings in Banyuwangi the first cases to pique your interest in witchcraft and magic?

Honestly, yes! Prior to learning about the killings, my interest in Indonesia had focused on cultural performance and literature. I first heard about the sorcerer killings in 1998. The killings troubled by me. I wondered, “How could there be a witch-hunt in modern times?” I also thought, “Who was behind the killings? Who benefitted from the killings?”

These questions, it turned out, were naïve and misplaced. But I asked myself these kinds of questions. Arriving in the field in 2000, I still assumed that the witch-hunt had nothing to do with magic, but was rather tied up with national political interests. While doing fieldwork (2000–2002), I began to realise that witchcraft and magic were crucial to understanding the killings. That was the first time my interest was piqued.

In Southeast Asia today, is the belief and practice of black magic and sorcery still very common?

As far as I can tell, belief in and practice of black magic and sorcery are very common. We could qualify that statement, as academics are wont to do, by questioning what we mean by “belief”, “practice”, “magic”, and “sorcery”. Nevertheless, studies from different parts of the region report on widespread suspicions. People suspect that their neighbour, colleague, rival, or whoever it might be draws on extraordinary or unseen powers for immoral ends. The people suspected are from the heights of power to the poorest and disenfranchised.

What were the challenges you faced during your field work in Banyuwangi when you undertook the task of conducting over 100 interviews for ethnographic research?

Professionally, the fieldwork was easy. People readily admitted to killing suspected sorcerers. Indeed, in some cases, they boasted and overstated their roles! By contrast, I struggled, personally. Initially I was horrified—I had to deal with ill health and exhaustion. I kept going primarily because I thought it was crucial to get an accurate historical record this massacre; especially as press and academic reports were so misleading. I wrote Witch-hunt and Conspiracy with this objective in mind.

This woman believed she had been ensorcelled. Her protruding stomach is visible from the profile. Dr Herriman is in the background. (Photo courtesy of L. Indrawati)

What are your thoughts about interdisciplinary studies? Upon reading your book, one can see that the historical and political contexts are very important to explaining how local dynamics or reactions to a situation came about (I.e., In your book, the context of 1998 being a period of Reformasi was very important in explaining how locals were reacting to political and social change after the fall of the Suharto government).

My feeling is that context is crucial in all studies of culture and society. Nevertheless, when I compare the anthropological approach with the interdisciplinary approach, I can discern differences in how to treat this context. Based on my fieldwork, the first book I wrote is called The Entangled State. I wrote this as an anthropologist. I was concerned with how the official treatment of the “problem of sorcery” in Banyuwangi could relate to anthropological theories about the state. I contended that the state was entangled in local communities. Because of this, I argued, senior bureaucrats are hamstrung in trying to contain the “problem of sorcery”.

Witch-hunt and Conspiracy is the second book I have written from my research on the sorcerer killings. I have focused closely on the killings themselves and attempted to understand them as an interplay between local dynamics and larger developments. I see this book as an interdisciplinary study in an area studies tradition. I like a diversity of approaches. The paradox of knowing the world is that each different understanding brings both insights and limitations. So I see pros and cons to both anthropological and interdisciplinary area studies.

So how did your academic background shape the way you approached the killings?

As a philosophy student I was introduced to the skepticism of David Hume and others. I was profoundly disturbed by questions about how we know what we think we know. Of course, I have no greater insight into these problems than most people. So the skeptical attitude remained with me. In research and writing Witch-hunt and Conspiracy, I continually challenged and questioned myself. In fact, after months and months of fieldwork the patterns of the killings began to seem clearer to me. I had begun to feel there was no conspiracy behind the killings. Yet I still did not trust appearances. So, for instance, when I interviewed people I would ask, “So who was behind the conspiracy?” Assuming that the truth remains hidden from me was my modus operandi in researching Witch-hunt and Conspiracy. I wanted, as much as possible, to be sure of my findings.

You are known as the “Audible Anthropologist”, having done a podcast series about anthropological concepts. What got you thinking about doing a podcast series as a way of promoting anthropology as a field of discipline and interest? And are you thinking of doing another season of podcasts, or a new series of podcasts?

I teach anthropology at university. Some of my students coming into second year subjects are new to anthropology. I wanted a quick and easy introduction to anthropological concepts. What I found online seemed more suitable for advanced learners. So I decided to produce a crash course myself. I asked La Trobe’s Matt Smith what to do. Matt currently produces La Trobe’s Asia Rising podcasts and other publications. Matt suggested a series of podcasts entitled “The Audible Anthropologist”. I then set myself a target of recording on a concept every workday for 25 days. This would stop me from over-complicating the content. Matt also got me studio time, told me how to record, and he edited the files. I hope that the result is a simplified introduction that even high school students could use. I got great feedback about that series, so I already have another series of podcasts on iTunesU. It’s called “Witch-hunts and Persecution”. This presents an anthropological view on past and present witch-hunts. It is part of my attempt to understand what I have presented in Witch-hunt and Conspiracy, in relation to witch-hunts internationally and throughout history.

NUS Press at the 2016 ASEASUK Conference September 16, 2016 12:30

NUS Press is pleased to be part of the 2016 edition of the Association for Southeast Asian Studies in the United Kingdom (ASEASUK) Conference at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). Held over three days this weekend (16-18 September), it is set to be the largest ASEASUK conference, with over 40 panels discussing a wide variety of topics.

NIAS Press is representing NUS Press at the event and will be displaying our books. Here’s a highlight of some titles:

|

|

- Catastrophe and Regeneration in Indonesia's Peatlands: Ecology, Economy and Society

- The Oil Palm Complex: Smallholders, Agribusiness and the State in Indonesia and Malaysia

- Marriage Migration in Asia: Emerging Minorities at the Frontiers of Nation-States

- Central Banking as State Building: Policymakers and their Nationalism in the Philippines, 1933-1964

- Electoral Dynamics in Indonesia: Money Politics, Patronage and Clientelism at the Grassroots

- Tall Tree, Nest of the Wind: The Javanese Shadow-play Dewa Ruci Performed by Ki Anom Soeroto - A Study in Performance Philology

- Pan-Asian Games and the Emergence of Modern Asia, 1913-1974

- Racial Science and Diversity in Colonial Indonesia

Dr Paul Kratoska, Publishing Director of NUS Press, will be also attending the Conference.

Do drop by to find out more about NUS Press and to browse our selection!