Five Minutes with Andrea Benvenuti June 21, 2017 12:00

With the recent publication of his new book, Cold War and Decolonisation: Australia’s Policy towards Britain’s End of Empire in Southeast Asia, Andrea Benvenuti seeks to challenge popular views—and misconceptions—of Australian relations with its neighbouring region during the Cold War. Moreover, Benvenuti, a senior lecturer in International Relations and European Studies at the University of New South Wales, offers a fresh and incisive look at the Australian perspective during the emergence of independent Southeast Asian nations and the collapse of British colonial rule.

With the recent publication of his new book, Cold War and Decolonisation: Australia’s Policy towards Britain’s End of Empire in Southeast Asia, Andrea Benvenuti seeks to challenge popular views—and misconceptions—of Australian relations with its neighbouring region during the Cold War. Moreover, Benvenuti, a senior lecturer in International Relations and European Studies at the University of New South Wales, offers a fresh and incisive look at the Australian perspective during the emergence of independent Southeast Asian nations and the collapse of British colonial rule.

In this edition of Five Minutes With …, Dr Benvenuti debunks the myths surrounding Australian political history, particularly those regarding the Menzies government, transplants his Cold War observations into the current political climate, and shares his upcoming projects.

What attracted you to the Australian policy perspective of the Cold War?

One of the enduring myths in Australian political history is that Australia failed to pursue an independent foreign policy in Asia during the early Cold War. As the story goes, under the Liberal–Country Party Coalition government of Sir Robert Menzies (1949–66) Australia overplayed the threat of international communism and became closely aligned with the United States and Britain in an effort to contain the spread of communism in Asia. However, by identifying itself too closely with American and British Cold War policies in Asia, the Menzies government, it is said, foreclosed any chance of engaging meaningfully with its neighbouring region and of developing a distinctive regional role for Australia. The underlying assumption here is that Australia would probably have been better off pursuing a neutralist foreign policy.

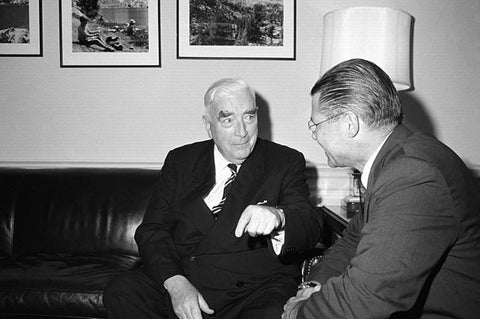

Robert Menzies (left) meets with US Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara at the Pentagon in 1964

(Image credit: Wikimedia Commons).

I have never been persuaded by these kinds of arguments and I thought I ought to find out more. I hope my book will provide a less distorted appreciation of Australia’s Cold War role in Asia and thus make a significant contribution to a better understanding of Australian policy concerns and interests, in a region of paramount strategic, political and economic importance.

What insights does your book offer on Australian foreign policy and relations with Southeast Asia that other historians may have neglected?

Another enduring myth in Australian history and politics is the idea that the Menzies years stand as a blot on the relationship between Australia and Southeast Asia. In Australian universities, scores of undergraduate and postgraduate students are taught to believe that Menzies’ conservative government had little interest in forging close and enduring links with Southeast Asia. According to the prevailing academic wisdom (one that is often embraced with gusto by the Australian media), Menzies’ Anglophilia and his keenness to nurture close ties with Australia’s ‘great and powerful friends’ (the US and Britain) prevented Australia from developing closer regional ties. Only with the arrival of Gough Whitlam at The Lodge (the Australian Prime Minister’s residence in Canberra) in 1972 did Australia begin to seriously engage with the region.

Nothing, of course, could be farther from the truth and my book shows just how grotesque this view is. Under Menzies, Australia pursued a policy of active and sustained regional engagement. Southeast Asia’s political stability and economic prosperity were of utmost importance to Menzies’ Australia, and the Liberal–Country Party government acted accordingly by placing regional engagement at the forefront of its foreign policy.

A clip of Gough Whitlam’s 1974 visit to the Philippines, which was part of a Southeast Asian tour to strengthen ties between the region and Australia. Whitlam also visited Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Laos, and Burma. (Source: Whitlam Institute YouTube Channel; footage courtesy of the National Film and Sound Archive and the National Archives of Australia [NAA 4423/31]).

The Menzies government expressed approval of Malaya and Singapore’s bids for merger and independence from British rule. How has this endorsement shaped Australia’s relations with Malaysia and Singapore since the Cold War era?

It has no doubt contributed to drawing Australia closer to Malaysia and Singapore, and forging an enduring and deep relationship with them.

In light of increasing nationalism amongst certain world powers, what lessons on navigating security and international relations from your book might be applicable today?

It is often difficult to compare the world of the 1950s or 1960s with our own. When I talk to my undergraduate students about the early Cold War years in Southeast Asia, I sometimes feel as if I am talking to them about ancient history, given that so much has changed at international and regional levels since then. With this proviso in mind, I venture to offer one possible lesson: as the history of modern Singapore and Malaysia clearly shows, regional political stability and economic prosperity are best maintained through a continuing and robust Western engagement with the region and vice-versa. Beijing’s version of ‘Asia for the Asians’ is really in no one’s interest.

What are your current research projects?

I am currently working on two projects: the first deals with Western (American, British and Australian) responses to the emergence of non-alignment in Asia during the 1950s and early 1960s. The second examines the role and impact of Western military power and strategic foreign policy in the ordering and re-ordering of Asia between 1919 and 1989. It is a collaborative international project sponsored by the Department of History at the National University of Singapore and led by Professor Brian Farrell.