News

Follow NUS Press on

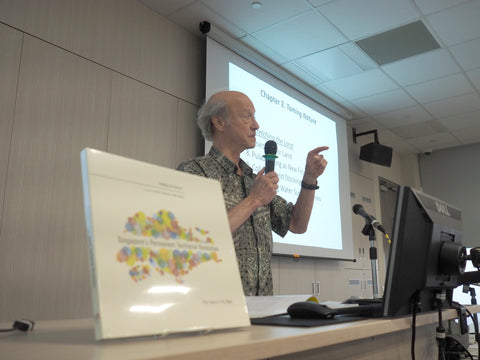

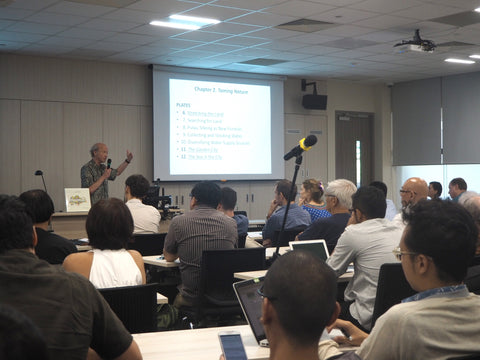

In Memoriam - John Miksic October 27, 2025 17:42

NUS Press mourns the passing of renowned archaeologist John Miksic, Emeritus Professor in the Department of Southeast Asian Studies at NUS.

learning the lessons of COVID-19 December 15, 2024 14:29

a stretch project for NUS Press - working with more than 100 top experts from the outbreak response community to put together the "state of the art" on pandemic preparedness.

Stateless - an ethnography of statelessness November 20, 2024 13:40

The plight of a stateless man in Singapore with no formal education and job prospects made national headlines recently, culminating in a wave of support and a job offer. As of Dec 31, 2023, there were 853 stateless people living in Singapore, and the UNHCR estimates that there are at least 4.4 million people who are stateless worldwide, including the Bajau Laut in Malaysia, the Yao, Hmong and Karen people in Thailand, the Kurds in Syria, and the Rohingyas, who make up the world's largest stateless population.Author Chen Tienshi Lara was born to Chinese parents in Yokohama’s Chinatown. When Japan terminated its diplomatic ties with the Republic of China (Taiwan) in 1972, she was one of the 9,200 Chinese residents rendered stateless. In her memoir, aptly titled Stateless, Chen deftly blends autobiography with a study of stateless communities around Asia, to explore questions of borders, mobility, belonging and identity.

NUS Press at AAS in Seattle - March 14 to 17 March 5, 2024 16:22

NUS Press is pleased to be exhibiting at the 2024 Asian Studies meeting #AAS24, in Seattle Washington. Director Peter Schoppert is on a panel to discuss trends in research publishing for Asian Studies, on Saturday at 4:00pm. If you would like to meet Peter to discuss this or other topics, please do book a meeting here.

NUS Press authors presenting at AAS include one of the editors of our new volume in the History of Medicine in Southeast Asia series, Fighting for Health: Michitako Aso.

Other NUS Press (and NIAS Press) authors giving papers at the conference include:

- Alicia Turner, Champions of Buddhism

- Allen Hicken, Electoral Dynamics in the Philippines

- Barbara Watson Andaya, contributor to Ghosts of the Past in Southern Thailand

- Leonard Andaya, Leaves of the Same Tree

- Brian Bernards, Writing the South Seas: Imagining the Nanyang in Chinese and Southeast Asian Postcolonial Literature

- Christina Schwenkel, Interactions with a Violent Past

- Edgar Liao, The University Socialist Club and the Contest for Malaya

- Elliott Prasse-Freeman, Unraveling Myanmar's Transition

- Eric Schluessel, Community Still Matters

- Faizah Zakaria, contributor to Singaporean Creatures

- George Dutton, contributor to Cross-Cultural Exchange and the Colonial Imaginary: Global Encounters via Southeast Asia

- Jenny Hedström, Waves of Upheaval in Myanmar

- Justine Chambers, Pursuing Morality

- Lisandro E. Claudio, Liberalism and the Postcolony

- Mary Callahan, Making EnemiesMaznah Mohamad, Melayu

- Meredith Weiss, The Roots of Resilience,Towards a New Malaysia?

- Mette Thunø, Beyond Chinatown

- Michele Ford, Workers and Intellectuals

- Min Ye, The Making of Northeast Asia

- Ole Bruun, Fengshui in China

- Tami Blumenfield, Doing Fieldwork in China ... with Kids!

- Vineeta Sinha, Southeast Asian Anthropologies

- Wataru Kusaka, Moral Politics in the Philippines

- Maris Diokno, editor of Chinese Footprints in Southeast Asia

Sorry if we left anyone out! We look forward to seeing you all soon.

Everyday Modernism wins the Colvin Prize! December 16, 2023 13:49

The annual prize is awarded by the Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain. From the judges' statement:

“The Colvin Prize 2023 is awarded to Everyday Modernism. The judges agreed that the collective endeavour of Jiat-Hwee Chang, Justin Zhuang and Darren Soh had created a book that was conceptually excellent, broad in scope, and ingenious in its use of different angles to explore the city of Singapore. The insightful text and specifically taken photographs combined to make a book that is eminently readable, a model for similar studies, accessible to a wide audience and an invaluable and lasting work of reference.”

We couldn't agree more. Here is some more background on the Association and on the Prize, from the Association's website.

The Colvin Prize

The Colvin Prize is awarded annually to the author or authors of an outstanding work of reference that relates to the field of architectural history, broadly conceived. All modes of publication are eligible, including catalogues, gazetteers, digital databases and online resources. It is named in honour of Sir Howard Colvin, a former president of the Society, and one of the most eminent scholars in architectural history of the twentieth century. The prize was inaugurated in 2017; winners receive a commemorative medal designed by contemporary medallist Abigail Burt.

Judging panel: Dr Elizabeth Darling (Chair of SAHGB + panel chair); Professor Richard Brook (Lancaster University School of Architecture); Professor Louise Campbell (University of Warwick); Dr Laura Fernández-González (University of Lincoln); Professor Simon Pepper (University of Liverpool); Dr Samantha Martin (University College Dublin).

The Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain brings together all those with an interest in the history of the built environment – academics, architects, heritage experts and the wider public. As the leading body in the field, we believe that appreciation of architectural history plays a vital role in understanding our culture, past and present.

NUS Press Acquires NIAS Press, Expanding Its Reach in Asian Studies Publishing November 14, 2023 15:56

NUS Press, the publishing arm of the National University of Singapore, is proud to announce its recent acquisition of the publishing operations of NIAS Press, the publisher of the Nordic Institute of Asian Studies in Copenhagen, Denmark. As announced in August this year, the Nordic Institute of Asian Studies is closing, but the research published by NIAS Press will continue to be made available around the world through the new arrangements.Malaysiakini - the heady days of Reformasi September 11, 2023 12:13

The following is an excerpt from Chapter Three of Malaysiakini and the Power of Independent Media in Malaysia, by Janet Steele, launched September 12, 2023.

CHAPTER 3 The Reformasi Generation

If you listened carefully, you started hearing conflicting plans from Anwar and Mahathir; that was one of the things that happened. Conflicting policy announcements. But still, it came as a huge shock that day when Anwar was suddenly dismissed. And that day and that time was the trigger for a whole new awakening among my generation.

Everything had seemed so good. The economy was growing; the just-opened Petronas Twin Towers and Kuala Lumpur International Airport were the envy of the region. Virtually full employment, annual GDP growth of upwards of 9 percent and very little inflation made Malaysia one of the best performing economies in Asia. Poverty had declined from around 60 percent in 1970 to about 9 percent in 1995—“an impressive record by any standard,” as the Asian Development Bank noted.1

In the center of it all was Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, a political powerhouse with an iron hand, no succor for his enemies and a bold vision for making Malaysia a fully developed country by 2020. Malaysiakini’s Ajinder Kaur, a student at the time, remembered:

The country was so peaceful, he is modernizing the nation, and he is this really great guy. We are moving ahead, and Mahathir had this Vision 2020 and says, “Oh, we are going to be this developed nation,” and it was indoctrinated in our textbooks, and we were made to study and present on it, and we think wow, 2020, we are going to be the next super-power of the world.2

“And Anwar,” she added. “Everyone saw Anwar and Mahathir as a really good pair, and they are going to bring—you know, we had so much hope in them.”

For anyone who had been paying close attention, however, like journalists from the Far Eastern Economic Review and Steven Gan of The Nation newspaper in Bangkok, there were signs that all was not well.3 Anwar Ibrahim, the charismatic deputy prime minister who also held the portfolio of finance minister, was known not to favor the big development projects of his boss. But these differences seemed minor until the Asian economic and financial crisis hit in 1997.

Abbot (2000: 249–50) notes that Anwar clearly favored austerity measures and cuts in government spending. Speaking out publicly against crony capitalism, he canceled a number of the administration’s high-profile infrastructure projects, including the Bakun Dam, the massive federal administrative center that would become Putrajaya, and a proposed bridge across the Straits of Malacca. Mahathir, on the other hand, favored government bailouts of politically connected conglomerates—at least one of which was controlled by his own son—and prestige companies such as Malaysia Airlines and the national car company Proton.

And then there was what had just happened in Indonesia, where President Soeharto was ousted by a coalition of pro-democracy activists that rallied around the slogan no KKN—korupsi, kolusi or nepotisme. As FEER noted, many of Anwar’s supporters believed it was the ousting of Soeharto that triggered the parting of the ways between Mahathir and his younger protégé:

In the past, Mahathir had repeatedly said he would step down as soon as he “read the signals.” Encouraged by developments in Indonesia, the Anwar camp sought to signal that the time had come for Mahathir to retire.

Anwar made a strong speech about “reform” prior to the run-up to June’s Umno assembly but stopped short of anything else. But his ally Zahid Hamidi, head of Umno’s youth wing, spoke out against “corruption, collusion and nepotism”—the same mantra delivered against Suharto. That was widely perceived as a direct attack on the premier by the Anwar camp.4

On September 2, 1998, Anwar was sacked from his position as deputy prime minister after he refused to resign. The reaction was immediate. Future Malaysiakini chief editor R.K. Anand, who was at UMNO headquarters at the time, remembered:

So we were all gathered, waiting downstairs, and the crowd is relatively calm. The Supreme Council members were upstairs in a meeting. And Anwar’s supporters, about 2,000 or 3,000 of them, were gathered down there. Before the meeting ends he comes down. He comes down and takes a plastic chair and puts it down and climbs on to it, and starts addressing the crowd with his fiery style. Says things like “you know they told me to resign; I refuse to resign. If I am going to fall, I will fall fighting. I will die as a warrior.” And that’s it. The whole crowd goes into a frenzy.

So as we were waiting there, after the meeting, after he left, the crowd was just going wild. And the police did not do anything because there would be bad press. You must remember that because of the Commonwealth Games, there was an overwhelming presence of foreign media there. So that’s why Mahathir came down. And it was for the first time that I actually saw people hurling plastic water bottles at him. His car was kicked and punched, the police had to form a human barricade around him, to get him safely into the car.5

The next day, September 3, the police filed affidavits charging Anwar with five counts of sexual impropriety (sodomy) and five charges of corruption. On September 20, he was detained under the ISA, until a preliminary hearing on the 29th at which he was denied bail.6

Meanwhile, the city erupted. Malaysiakini editor Martin Vengadesan, at that time a music critic for The Star newspaper, remembered:

So suddenly there was an increase in student activism, there were young people joining opposition parties, Parti Rakyat, the youth movement; suddenly you had five times more people than you used to. Then they formed the new party as well, Keadilan [Justice]. Every week there was some escalation. You know the picture of him being beaten up was another sign to people that this façade of a very democratic Malaysia was not true. If the second most powerful person in the country could be toppled so suddenly and fall so hard, and be bashed up behind bars, what more the ordinary person?7

Or, as Ajinder said, “So we always thought like everything is nice and beautiful, and the media made it seem that way as well. So suddenly, when Anwar got sacked, it was like, ‘Oh my God, what is happening to my country?’ ”

Anwar

Young Malaysians had never seen anything like it. In an era in which even cell phones were scarce, there were protests and speeches at Dataran Merdeka, and nightly gatherings at Anwar’s house in Bukit Damansara, a posh neighborhood which R.K. Anand remembers as being full of “fancy restaurants and whatnot” but not food that ordinary people could afford.8

As friends and well-wishers called on Anwar, the atmosphere outside became almost carnival-like, as thousands of people thronged his house, night after night. Soon vendors started to arrive. “You had sate reformasi, laksa reformasi, people trying to cash in on it,” Anand said. “So it turned into this whole night market kind of thing. And DBKL [the KL City Council] came and put in portable toilets and all this.”

FEER journalists Murray Hiebert and Andrew Sherry noted a few days after Anwar’s ouster that the drama seemed unlikely to blow over, as the former deputy prime minister obviously had a lot of support. “Each day since his ouster, thousands of people—ranging from punk rockers with orange-dyed hair to bearded Islamic teachers, businessmen, activists and opposition politicians—have come to visit the former minister at his relatively modest private house in Kuala Lumpur,” they wrote. “ ‘You groom him like a son, then you kill the son,’ grumbles a middle-aged businessman sitting outside Anwar’s house.”9

A few days later, on September 20, the biggest rally began at the national mosque. Eyewitnesses described Anwar’s calls for reformasi and the display of emotion that greeted them as unprecedented, “the largest opposition rally the country had seen in three decades.” FEER reported:

Alternating chants of Allah-hu Akbar—God is great—with invective against Mahathir, the crowd roared Anwar on as he denounced what he called a conspiracy against him and called for the prime minister to resign. At Anwar’s request, the crowd then made its way to the city’s symbolic heart, Merdeka Square, where independence was declared in 1957. Breaking through police barriers, throngs that had now swelled to about 50,000 people poured into the grassy square to hear further condemnation of the government.10

After Anwar left, part of the crowd marched past the Sogo shopping complex towards the headquarters of UMNO, where they allegedly broke windows and tore down posters of UMNO leaders. Heading towards Mahathir’s residence and demanding his resignation, the crowd of supporters—now estimated at 35,000—was stopped by riot police, who began firing tear gas. Human Rights Watch reported that Anwar was arrested at his home later that night by police armed with assault rifles.

On September 21, the riot police used tear gas and water cannons to disperse the crowd that was awaiting Anwar’s appearance at the courthouse. The police made about 100 arrests, “some of them accompanied by beatings.”11

Anand remembered:

When I look back at it in hindsight, it was probably the most brilliant experience of my journalistic career. And I can safely tell you with a high degree of confidence that it was Mahathir who created Reformasi. It wasn’t Anwar. Because you would expect someone who is a deputy prime minister and a really popular leader, and the unceremonious manner in which he was sacked, you would expect protests to take place. And when these protests took place, you immediately come down so hard on the protesters, firing away with your water cannons and tear gas, just for a bunch of people who are gathering. And that stoked the anger, and that just snowballed and snowballed and snowballed, and they started seeing Mahathir as an oppressor, the whole regime as being oppressive, and it just exploded.

Eighteen Days

Each of Malaysia’s mainstream news organizations is either owned by or affiliated with a particular segment of the ruling coalition (Gomez 2004; Nain and Anuar 1998). The Star, Malaysia’s largest English-language daily, is owned by the Malaysian Chinese Association, a partner in the ruling Barisan Nasional. The New Straits Times Press group, which publishes both the English-language New Straits Times and Malay broadsheets Berita Harian and Utusan Malaysia, is owned by UMNO’s holding company, Fleet Holdings Sdn Bhd. The Tamil papers are under the control of the Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC).

There are no better media critics than Malaysian journalists. Carefully attuned to the placement of every word and the nuance of every sentence, they also interpret editorial “reshuffles” with admirable precision. In the 1990s, everyone knew that while the press was controlled by the ruling coalition, it was Mahathir who called the shots. In remembering the events of Reformasi, Malaysiakini editors R.K. Anand and Jegathesan Govindaraju noted that a key moment had occurred about one month before the move against Anwar, when Mahathir “transferred out” senior editors in key press positions who were deemed loyal to Anwar.

FEER noticed this too. Calling it a “media putsch,” the weekly observed on July 30 that in the space of one week, Johan Jaafar and Nazri Abdullah, “both staunch Anwar allies,” had resigned as editors of Utusan Malaysia and Berita Harian.

Meanwhile, over at TV3, a free-to-air television channel also owned by the UMNO-linked Media Prima group, a young producer named Wee Yu Meng, now a Malaysiakini editor on the Bahasa Malaysia desk, had received some odd instructions. About one month before Anwar was sacked, he recalled, they had been instructed to add into the daily newscast the statement that “nobody is above the law.” Although he did not fully understand “the agenda” at the time, now he knows that it was “to prepare the mindset of the people.”12

“We get academicians, we get the police, we get everybody to psych out the public,” he remembered. “Nobody is above the law.”

Once Anwar was sacked, it was even worse, Wee said:

You see it is very difficult for us in TV3 and Berita Harian. Because we are directly under UMNO. We are the ones who built Anwar’s character from nobody to deputy prime minister. We built his image, okay? And I remember doing dirty jobs for Anwar too. He attacked Sanusi Junid, the agriculture minister. For almost a month, every night I have to go to Tanjong Karang, which is about two to three hours’ drive away, to show that rats are destroying the paddy field, and the farmers are suffering. I did a lot of propaganda work. So, like I say, I have done so many many things, some of them of which I’m not proud.

At TV3, where the vast majority of journalists were Malay, there was considerable support for Anwar, and also a lot of confusion. Remembering those days, Wee said, “We were lost. Totally lost. We really didn’t know how to react. To follow orders or not to follow orders. We were so divided.”

The management at TV3 quickly brought in new bosses. Kadir Jassin came in, and Chamil Wariya from Utusan Malaysia. Chamil’s job was to “clean the TV3 newsroom.” Anyone—down to the reporter’s level—who was not in line with Mahathir was told either to resign or be transferred elsewhere.

TV3 covered the demonstrations, but it wasn’t easy. Wee remembered Anwar’s ceramah at Masjid Negara. “When he talked about TV3, the supporters started to throw ice cubes on us,” Wee said.

So Anwar says “relax, it’s not them. It’s higher up than them.” So we are saved. Then our vehicles got damaged in a few incidents. Wherever we go, we are no longer being loved. Previously they loved TV3 … so it’s totally changed, everything. They break our vehicles, they beat some of us. Things like that.

Why was TV3 even covering the demonstrations? For the slightly sinister reason that the government wanted to have a record of what happened. “Most of it was never broadcast,” Wee added.

Given eyewitness accounts, it is not surprising that the ceramah were never broadcast. Anand remembers:

He is a fiery orator. That is why in hindsight, in retrospect, when I look at it, I was truly amazed. Because this was a man who was deputy prime minister, who was accustomed to life as a VIP, and when all of that was removed from him, within a matter of 24 hours, I actually saw him transformed into a street fighter almost instantaneously. He did not even take a day or two to wallow in self-pity, to cry over spilled milk. Immediate transformation!

There were more instructions for TV3. “We must not show any crowds, people who are supporting Reformasi, things like that. But anything to do with violence, yes,” Wee said. But when they showed the violence, they also showed the size of the crowd, and the bosses realized “it’s not working; it’s backfiring.”

“So we are told to completely stop. So the producers, we have to make sure that the visuals that we transmit don’t have anything that can be negative to Mahathir’s administration.”

“To be very honest with you,” Wee added, “most of us are sympathizers. But we know there’s a lot of spies. People who will report who is what, things like that. We believe there are Special Branch people, so we are always very worried about what we say, what we do, we don’t do it openly.”

Enter Malaysiakini

It was October 1999, and Ajinder Kaur was fresh out of university and looking for a job. An English major, the two options seemed to be teaching and writing. She liked to write, and when she saw a notice in the Malay Mail classified advertisements saying that Malaysiakini was looking for a reporter, she sent an email straightaway to Steven Gan asking for an interview. The office was in a fourth-floor shop lot in Section 14 of Petaling Jaya, near the Jaya Supermarket. It had been an architect’s office.

“So being a fresh graduate,” she remembers, laughing,

you think you’re going to go to this very glamorous job, but when I walked in, there was no office set up, it was Steven and Prem, and the interview was at the back of this shop. The previous tenant had kitchen cabinets on the wall; it was the pantry! And I think that Steven was living in that place as well! I was like, oh my God, what is this office? Does this organization even exist?

The atmosphere was so warm, though, that once she heard exactly what the mission was, she knew immediately that this was something she wanted to do.

.... chapter continues...-

1 Asian Development Outlook 1996 and 1997. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, p. 94.

-

2 Interview with Ajinder Kaur, Dec. 19, 2019.

-

3 See, for example, Murray Hiebert “Mixed signals,” Far Eastern Economic Review 161(21): 24–8.

-

4 S. Jayasankaran “Protégé to pariah,” Far Eastern Economic Review 161(38): 13–14.

-

5 Interview with R.K. Anand, Nov. 25, 2019.

-

6 Details come from Abbot (2000: 246).

-

7 Interview with Martin Vengadesan, Nov. 26, 2019.

-

8 Interview with R.K. Anand, Nov. 25, 2019.

-

9 Murray Hiebert and Andrew Sherry (Sept. 17, 1998) “After the fall,” Far Eastern Economic Review 161(38): 10–13.

-

10 Simon Elegant, Murray Hiebert and S. Jayasankaran (Oct. 1, 1998) “First lady of reform,” Far Eastern Economic Review 161(40): 18–20.

-

11 “First lady of reform,” ibid.

-

12 Interview with Wee Yu Meng, Nov. 27, 2019.

Going to the AAS - on the road again February 23, 2023 15:15

NUS Press will be on stand 202 at the Association for Asian Studies meeting in Boston, MA. We will be looking forward to greeting so many NUS Press authors, including AAS Keynoter Pasuk Phongpaichit. Come by to see the latest titles, and a preview of what's coming up next. Pick up books or place orders at special conference discounts.

If you would like to find a time to meet Publisher Peter Schoppert, please book using the Calendly app, below.

Talking about the Book : Celluloid Colony September 18, 2022 12:23

Join Sandeep Ray, author of Celluloid Colony: Locating History and Ethnography in Early Dutch Colonial Films of Indonesia, in discussion with Indonesian film scholar Thomas Barker and Indonesian film archivist Lisabona Rahman, moderated by NUS Press Director Peter Schoppert.

How can colonial propaganda or missionary films be used as primary sources for historical or anthropological research? What does one need to know about the circumstances of their production in order to read them better? What distinguishes Dutch colonial film from its British counterpart?

Watch the video for your special 20% discount code (good till end September 2022). (Yes, you can fast forward...but you will be missing a very nice conversation.)

Call for Manuscripts - New Book Series April 29, 2022 12:28

Across the Global South: Built Environments in Critical Perspective

Books in this series take the built environment as a lens to foreground the struggles of various stakeholders in both historical and contemporary contexts. They address the task of writing "across the Global South" as an ethical, intellectual, and political project that builds new communities of readership. Established and emerging scholars across disciplinary divides and whose work addresses the scope of the series are welcome to approach the Press and the editors with their proposals.

Series Editors: Anoma Pieris (U of Melbourne); Farham S Karim (U of Kansas); Lee Kah Wee (NUS),

Please send proposals or expressions of interest to: nus_press_submissions@nus.edu.sg

A.L. Becker Prize winner: A New Sun Rises Over the Old Land March 1, 2022 17:23

NUS Press’ A New Sun Rises Over the Old Land: A Novel of Sihanouk’s Cambodia (2019), by Suon Sorin and translated by Roger Nelson, has been awarded the A.L. Becker Southeast Asian Literature in Translation Prize by the Association for Asian Studies (AAS).

Mining the Visual Record: a View from Southeast Asia’s Archipelagic Far East May 10, 2021 23:30

by Heather Sutherland

This personal consideration of the graphic archive is like a photograph, capturing only a particular moment in time. Nonetheless, I hope my experience in compiling an image gallery on the easternmost part of Southeast Asia, will prove helpful to readers.

Evolving technologies have created a constantly expanding visual repertoire, which is now uniquely accessible through digital media. The revolution in saving, transferring, and printing images gained critical mass in the 1990s, although Benny Landa's Indigo Digital Press dates back to 1977 and the predecessors of the Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG) to 1983. The consequent disruptions have created challenges and opportunities for those in the knowledge business. Producers1 and consumers alike are adjusting, trying to catch up. There is now a global library of texts and images; this has fundamentally changed cost-benefit calculations in research. The effort needed to assess material has changed utterly. Many sources, once dismissed as taking too much time to check, given that the only reward might be few meagre facts or images, can now be reviewed in minutes. Once obscure sources and collections can be readily explored, creating new angles of vision.

Methodologies of textual criticism, with their roots in Biblical analysis, philology, and studies of the classics, have always been fundamental to the humanities. However, as the advertising industry learned long ago, visual information is more appealing, and absorbed more immediately, than blocks of text. But it is difficult to subject images to the same logical rigour as written argument, causing some ambivalence among those who cherish the scientific basis of their discipline. Intent and affect in sources are hard to pin down. The "scope of digital methods related to images and other visual objects based on vision rather than close reading remains…essentially uncharted",2 despite the surge of interest in (often quantitative) research in the digital humanities.3

It is not my intention here to embark upon these waters; nor do I consider the debate on the relationship of visual material to structures of knowing, power and identity. 4 Rather, I want to convey personal, practical and hopefully useful information drawn from my own experience. The focus is upon images intended as documentation of archipelagic Southeast Asia, not those created for expressive or artistic reasons.

While working on a book on trade and the state in these eastern archipelagos of Southeast Asia, Seaways and Gatekeepers I realised how unfamiliar they were to me, even after decades of interest in Indonesia and Malaysia. I found that images – drawings, maps and photographs – were indispensable in building some understanding of the region's diversity. I knew that this would be even more true for most of my readers. A book could not encompass a fraction of the material I wanted to present. When NUS Press suggested a dedicated website, I was enthusiastic. I had earlier been involved in various attempts to develop online resources, which had foundered because there was no suitable platform.

I envisaged the website as a digital appendix. The functions of academic appendices are similar to those of the human anatomical kind, both being remnants of earlier evolution, while harbouring useful resources (bacteria, in the human gut). Traditionally academic appendices were used to present blocks of relevant material that would have interrupted the flow of the main text. Now the digital material that can be presented is infinitely more diverse, encompassing images, sound and text. A digital appendix can have diverse function, either being integrated closely with the article or book, or a separate yet engaging experience. This could also be updated. Even so, in 2019 the widely used American Psychological Association style sheet specified that appendices "should not burden the reader" and be "easily presented in print format". The examples then given would have been familiar almost two centuries earlier – think of Raffles’ History of Java (1830).6

So now we have an “appendix” attached to my Seaways study, which ranges in time from the early sixteenth to the early 20th century. Our material consists of images and maps. The zoomability of digital graphics is a great advantage; see for example the detailed drawing of the defeat of Makassar in the 1660s, available through the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum, or the wonderful map of the eighteenth century Philippines provided by the US Library of Congress to the UNESCO Digital Library. 7 The digital collection of the Brazilian Overseas Council (O Conselho Ultramarino), heir to the Portuguese establishment founded in Lisbon in 1643, has a fascinating seventeenth century sketch map of Melaka.8

Explorations

Authors working on modern Indonesia used to have a simple task when looking for illustrations: they went to the KITLV in Leiden or the KIT in Amsterdam, leafing through lists. The publisher would grudgingly permit a handful of black and white images; colour images were expensive and rationed. Now the prospects seem unlimited, continually increasing in range and depth. The visual record is global, and the researcher not only has access to individual institutions and personal snapshots, but also to a growing array of national and trans-national platforms that create multi-collection resources. Teachers have ample opportunities to introduce their students to primary sources, encouraging them (for the VOC period alone) to view original documents,11 browse manuscripts,12 and search archive catalogues.13 Heritage funding has helped generate a spate of new sites. Platforms are typically administered by national libraries, such as Australia's Trove (2010), France's Gallica and Spain's Biblioteca Digital Hispánica (2008). The US Library of Congress prints and photograph collections have some material on Southeast Asia. The Smithsonian Institution's research information system (SIRIS) offers access to a maze of collections, but it is best to use their open access portal (opened 2020). The National Library of the Philippines has extensive text collections, from incunabula to newspapers, and a good map collection. Heritage-related material is available from the National Library Board of Singapore19 and more general images, including historical, from the National Archives of Singapore online. Malaysia's National Archives library is searchable, with a variety of material, including documents.20

Transnational platforms include those linked to the European Union, such as Europeana and, since 2006, EuropArchive. Several Dutch maritime museums have pooled their resources in Maritiemdigitaal, while the Ministry of Defence hosts the NIMH, the Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire Historie.

Since 1999 the Netherlands government has been developing the Digital Heritage Network (DEN), based in the National Archives. The Ministry of Education and Culture's cultural heritage service maintains its own website,21 as well as supporting others, such as the recently renewed Geheugen van Nederland. This now provides access to the National Collection of the Netherlands and photographs from the National Archives. Government funding has also been invested in soft power projects involving former colonies.22 The Dutch National Archives, a world leader in digitalisation projects, offers documents online and collaborates with former colonies. The Atlas van Mutual Heritage (AMH) repackaged the visual legacy of the Dutch East and West India Companies, including maps; the linking of the historic image to the current Google Maps location is an extra twist. The Indonesian National Archives (ANRI) online resources now include the Batavia Daghregisters (the VOC diary of events), the De Haan map collection, Siam diplomatic letters and many lesser collections useful for Batavia's urban social history.23 The Harta Karun project is among ANRI initiatives funded by the Corts Foundation. This offers annotated key documents and is an excellent way of making historical texts more accessible.24

Useful sources can be found in specialist institutions such as the medicine-focussed Wellcome Library (1949) and those of universities.25 The latter encompass the Guillemard collection of photographs and diaries from the 1886 expedition to the eastern archipelagos,26 now kept in the Cambridge University Library, the University of Texas map collection, Michigan's extensive holdings (with a focus on the Philippines), those of Cornell and Wisconsin, or, less predictably, Bristol's impressive Visualising China or Lafayette University's images of pre-war Indonesia.27

Using illustrations from books and periodicals once required visits to libraries. Then Project Gutenberg (1971) led the way to free access to digital texts, followed by others, such as Internet Archive (1996) and the Hathi Trust (2008). The Internet Archive, for example, has a modest 500 titles for Celebes but 16 films. The latter has over half a million full-text books relating to the Dutch East Indies, over 550,000 references to Celebes, and 34 for humble Hoamoal. It also hosts the Wayback Machine, an evolving, and easily searchable, internet archive of the internet; this began in 1996. The Hathi search function locates periodical articles from, for example, the Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, complete with coloured plates.28 For the Netherlands, Delpher (2013) has become an indispensable resource. Not only has it digitalised colonial newspapers (partly searchable) but is also offering an ever-growing selection of Dutch books. Now that there are often multiple copies online it is possible to compare different versions of the same work. The results of two nineteenth century scientific commissions in the Indies can act as example: Caspar G.C. Reinwardt's Royal Commission on Agriculture, Science and Art in the colonies, which began research in the Indies in 1816,29 and Coenraad Jacob Temminck's Natuurkundige Commissie voor Nederlandsch-Indië , established in 1820. 30

Reinward's Reis31 is available in Google and Delpher versions, while Salomon Müller's ethnographic work for the Temminck commission (1838) is best consulted as one of the many well-presented and searchable works in the Biodiversity Library (est. 2005).32 Nineteenth century travel accounts are also online, including those of Kolff33, van der Hart34, van der Crab35, and a selection of voyages to West New Guinea.36 Digital versions of classics on the eastern islands such as Riedel37 and de Clercq38 are also available. The former is offered through Columbia University, while the Smithsonian Library provides both the Dutch original and an English translation of de Clercq's Ternate.

One useful feature of online collections is that the copyright situation is relatively clear. It is usually specified what is public domain, and what is covered by a Creative Commons license. These were introduced in 2002 and enable copyright holders to grant general access to their material, breaking from the general guideline that an author's rights are protected until seventy years after his or her death. Such information removes the uncertainties surrounding "fair use", as (vaguely) defined in the United States.

Conditions of obtaining material have also been transformed. Once carefully selected images were provided at a cost per copy or negative, prices ranging from the exorbitant to the reasonable. The proliferation of images online, and the inability to control their distribution, necessitated new pricing structures. Some institutions still charge fees for access to high resolution copies as well as for publishing permission (the British Library) others, such as Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum, make all images already in high definition available online free of charge. This generosity is increasingly common, other examples being the New York Public Library, the KITLV, all online material provided by the Dutch Koninklijke Bibliotheek (KB) and Nationaal Archief (NA) (National Library and Archives respectively), and any on Wikimedia Commons. Others adopt a middle course, charging a flat fee per publication (the NMVW).

A final suggestion: it saves considerable time and trouble if the image and all the information necessary for citation (including copyright and persistent url) are well organised from the very beginning. Since image files are large, it is better not to store them inside the database itself, but to have a designated field in the informational database that provides a path or link to the specific image file. These can be kept in the local file system or stored on the cloud. If several people are collaborating on a large project a cloud-based platform can make transmission of files and data relatively easy; Airtable, which combines features of a spreadsheet and database, is an example. For smaller projects a simple database such as Access can store information, while images can be linked to the Access form.

This overview has focussed on the evolution of the pre-twentieth century graphic repertoire, and digital access to it. The potential is even greater for research on contemporary issues, when material created within the digital environment can be called upon. Sound, still images, film, video and the stream of digital media themselves will all contribute. The Netherlands Sound and Image Archive has newsreel and other material from the Netherlands Indies and Indonesia, while more films are available from the EYE Museum.39 The exploitation of television footage, blogs, YouTube and so on, will demand focussed attention as well as methodological and theoretical discipline. We have barely begun.

Sources

Aa, P.J.B.C. Robide van der. Reizen Naar Nederlandsch Nieuw-Guinea : Ondernomen Op Last Der Regeering Van Nederlandsch-Indie in De Jaren 1871, 1872, 1875-1876 / Door De Heeren P. Van Der Crab and J.E. Teysmann, J.G. Coorengel En A.J. Langeveldt Van Hemert En P. Swaan ; Met Geschied- En Aardrijkskundige Toelichtingen Door P.J.B.C. Robide Van Der Aa. 's-Gravenhage: Nijhoff, 1879.

Bate, David. "Photography and the Colonial Vision." Third Text 7, no. 22 (1993): 81-91.

Clercq, F. S. A. de. Bijdragen Tot De Kennis Der Residentie Ternate. Leiden: Brill, 1890.

Crab, Petrus van der. De Moluksche Eilanden: Reis Van Z. E. Den Gouverneur-Generaal Charles Ferdinand Pahud, Door Den Molukschen Archipel. Batavia: Lange, 1862.

Dobson, James E. Critical Digital Humanities: The Search for a Methodology. Chicago: University of Illinois, 2019.

Eleanor M. Hight, Gary D. Sampson, ed. Colonialist Photography. Imag(in)Ing Race and Place. London: Routledge, 2002.

Fox, Justin. "Covid-19 Shows That Scientific Journals Need to Open Up. Publishers Have Had a Good 355 Years, but Change Is Coming." Bloomberg Opinion 30 June 2020 (2020).

Guillemard, Francis H.H. The Cruise of the Marchesa to Kamchatka & New Guinea with Notices of Formosa, Liu-Kiu, and Various Islands of the Malay Archipelago. 2 vols. London: John Murray, 1886.

Hart, C. van der. Reize Rondom Het Eiland Celebes En Naar Eenige Der Moluksche Eilanden, Gedaan in Den Jare 1850, Door Z.M. Schepen Van Oorlog Argo En Bromo, Onder Bevel Van C. Van Der Hart. vols. s'Gravenhage: K. Fuhri, 1853.

Ignatow, Gabe, and Rada Mihalcea. Text Mining: A Guidebook for the Social Sciences. London: SAGE Publications, 2017.

Kolff, Dirk Hendrik. Reis Door De Weinig Bekende Zuidelijke Molukse Archipel En Langs De Geheel Onbekende Zuidwestkust Van Nieuw-Guinea, Gedaan in De Jaren 1825 En 1826. Amsterdam1828.

Koole, S. "Photography as Event: Power, the Kodak Camera, and Territoriality in Early Twentieth-Century Tibet." Comparative Studies in Society and History 59, no. 2 (2017): 310-345.

Maron, Nancy, Kimberly Schmelzinger, Christine Mulhern, and Daniel Rossman. "The Costs of Publishing Monographs: Toward a Transparent Methodology." Journal of Electronic Publishing 22, no. 1 (2016).

Müller, Salomon. "Land-En Volkenkunde. Verhandelingen over De Natuurlijke Geschiedenis Der Nederlandsche Overzeesche Bezittingen." edited by C.J. Temminck Natuurkundige Commissie voor Nederlandsch-Indie. Leiden: S. en J. Luchtmans en C.C. van der Hoek, 1839.

Protschky, Susie, ed. Photography, Modernity and the Governed in Late-Colonial Indonesia. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2015.

Raat, A.J.P. "Alexander Von Humboldt and Coenraad Jacob Temminck." Zoologische Bijdragen 21 (1976): 19-38.

Raffles, Sir Thomas Stamford. The History of Java. Volume 2. London: J. Murray, 1830.

Reinwardt, C.G.C. Reis Naar Het Oostelijk Gedeelte Van Den Indischen Archipel, in Het Jaar 1821. Amsterdam: F.Muller, 1858.

Riedel, J. G. F. . De Sluik-En Kroesharige Rassen Tusschen Selebes En Papua. Gravenhage: M. Nijhoff, 1886.

Rosenberg, H. von, and W. Vogler. "De Mentawai-Eilanden En Hunne Bewoners." TITLV 1 (1853): 399-442.

Sander Münster, Melissa Terras. "The Visual Side of Digital Humanities: A Survey on Topics, Researchers, and Epistemic Cultures." Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 35, no. 2 (2019): 366-389.

Strassler, Karen. Refracted Visions: Popular Photography and National Modernity in Java.. Durham: Duke, 2010.

Sutherland, Heather. Seaways and Gatekeepers. Trade and State in the Eastern Archipelagos of Southeast Asia, C.1600–C.1906. Singapore: NUS, 2021.

Weber, Andreas. Hybrid Ambitions. Science, Governance, and Empire in the Career of Caspar G.C. Reinwardt (1773-1854). . Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2012.

- Nancy Maron et al., "The Costs of Publishing Monographs: Toward a Transparent Methodology," Journal of Electronic Publishing 22, no. 1 (2016). The most contentions arena has been periodical publishing, where gatekeeping scientific journals enjoy profit margins of up to forty per cent Elsevier (RELX) has been a particular focus of criticism; the firm, inspired by a sixteenth century Leiden business, was founded in 1880 and now issues between 2,500 and 2,000 journals. It has been a fierce opponent of Open Access. Justin Fox, "Covid-19 Shows That Scientific Journals Need to Open Up. Publishers have had a good 355 years, but change is coming.," Bloomberg Opinion 30 June 2020 (2020). Wikimedia, "Elsevier".↩

- Melissa Terras Sander Münster, "The visual side of digital humanities: a survey on topics, researchers, and epistemic cultures," Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 35, no. 2 (2019).↩

- Gabe Ignatow and Rada Mihalcea, Text Mining: A Guidebook for the Social Sciences (London: SAGE Publications, 2017). James E. Dobson, Critical Digital Humanities: The Search for a Methodology. (Chicago: University of Illinois, 2019).↩

- For example: David Bate, "Photography and the colonial vision," Third Text 7, no. 22 (1993). Gary D. Sampson Eleanor M. Hight, ed. Colonialist Photography. Imag(in)ing Race and Place (London: Routledge, 2002). Karen Strassler, Refracted Visions: Popular Photography and National Modernity in Java.. (Durham: Duke, 2010). Susie Protschky, ed. Photography, modernity and the governed in late-colonial Indonesia (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2015); S. Koole, "Photography as Event: Power, the Kodak Camera, and Territoriality in Early Twentieth-Century Tibet," Comparative Studies in Society and History 59, no. 2 (2017).↩

- Heather Sutherland, Seaways and Gatekeepers. Trade and State in the Eastern Archipelagos of Southeast Asia, c.1600–c.1906 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2021).↩

- Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, The history of Java. Volume 2. (London: J. Murray, 1830).↩

- 1734. Una carta hidrográfica y corográfica de las islas Filipinas, Bibloteca Digital Mundial. On the Library, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/about#↩

- “Fortaleza de Malaca” from their collection [Fortificações portuguesas - Ásia - Mapas - Obras anteriores a 1800][http://objdigital.bn.br/objdigital2/acervo\_digital/div\_cartografia/cart1102901/cart1102901.jpg](http://objdigital.bn.br/objdigital2/acervo_digital/div_cartografia/cart1102901/cart1102901.jpg)↩

- For the wills of VOC officials and subjects, https://www.nationaalarchief.nl/onderzoeken/zoekhulpen/voc-oost-indische-testamenten↩

- Such as the journal kept by Arnoldus Lieranus on this travels kin Amboina, 1631-1635, in the Badische Landesbibliothek, Karlsruhe, Cod. Karlsruhe 476, https://digital.blb-karlsruhe.de/blbhs/content/titleinfo/3414157↩

- See the TANAP overview: http://www.tanap.net/content/activities/inventories/index.cfm↩

- https://ubl.webattach.nl/apps/s7↩

- https://geheugen.delpher.nl/nl↩

- https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collections/↩

- https://www.si.edu/openaccess↩

- http://web.nlp.gov.ph/nlp/?q=node/2682↩

- https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/pictures/Browse/Heritage\_and\_Culture↩

- https://images.nationalarchives.gov.uk/assetbank-nationalarchives/action/viewHome↩

- https://www.collectienederland.nl/↩

- On the Shared Cultural Heritage Programme see https://english.cultureelerfgoed.nl/topics/shared-cultural-heritage/shared-cultural-heritage-programme. This also includes the Atlantic World, in co-operation with the library of Congress.↩

- Harta Karun was part of the Corts Foundation funded DASA project (2011-2018); see the website of the foundation: https://www.cortsfoundation.org/about-us/projects/dasa. Also https://sejarah-nusantara.anri.go.id/↩

- For the VOC period alone, the TANAP programme and the digitalisation of documents (such as testamenten↩

- For the UCLA's overview of Southeast Asian Images Resources, go to: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/c.php?g=180226&p=1184977↩

- Francis H.H. Guillemard, The Cruise of the Marchesa to Kamchatka & New Guinea with Notices of Formosa, Liu-Kiu, and Various Islands of the Malay Archipelago, 2 vols. (London: John Murray, 1886).↩

- East Asia Image Collection, Gerald & Rella Warner Dutch East Indies Negative Collection;↩

- The first number, for example, contained H. von Rosenberg and W. Vogler, "De Mentawai-eilanden en hunne bewoners," TITLV 1(1853). This included 2 maps and 26 plates. Access limited for post-1879 volumes.↩

- Andreas Weber, Hybrid Ambitions. Science, Governance, and Empire in the Career of Caspar G.C. Reinwardt (1773-1854). (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2012).↩

- A.J.P. Raat, "Alexander Von Humboldt and Coenraad Jacob Temminck," Zoologische Bijdragen 21(1976).↩

- C.G.C. Reinwardt, Reis naar het oostelijk gedeelte van den Indischen archipel, in het jaar 1821 (Amsterdam: F.Muller, 1858).↩

- Salomon Müller, "Land-en Volkenkunde. Verhandelingen over de Natuurlijke Geschiedenis der Nederlandsche overzeesche bezittingen," ed. C.J. Temminck Natuurkundige Commissie voor Nederlandsch-Indie (Leiden: S. en J. Luchtmans en C.C. van der Hoek, 1839).↩

- Dirk Hendrik Kolff, Reis door de weinig bekende zuidelijke Molukse archipel en langs de geheel onbekende zuidwestkust van Nieuw-Guinea, gedaan in de jaren 1825 en 1826 (Amsterdam1828). The English version is also online.↩

- C. van der Hart, Reize rondom het eiland Celebes en naar eenige der Moluksche eilanden, gedaan in den jare 1850, door Z.M. schepen van oorlog Argo en Bromo, onder bevel van C. van der Hart, https://books.google.nl/books?id=eoppAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=inauthor:%22C.+van+der+Hart%22&hl=nl&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwicirjEzIftAhUEqaQKHeUGCSQQuwUwAHoECAMQBg#v=onepage&q&f=false vols. (s'Gravenhage: K. Fuhri, 1853).↩

- Petrus van der Crab, De Moluksche eilanden: Reis van Z. E. den Gouverneur-Generaal Charles Ferdinand Pahud, door den Molukschen Archipel (Batavia: Lange, 1862).↩

- P.J.B.C. Robide van der Aa, Reizen naar Nederlandsch Nieuw-Guinea : ondernomen op last der regeering van Nederlandsch-Indie in de jaren 1871, 1872, 1875-1876 / door de heeren P. Van der Crab and J.E. Teysmann, J.G. Coorengel en A.J. Langeveldt van Hemert en P. Swaan ; met geschied- en aardrijkskundige toelichtingen door P.J.B.C. Robide van der Aa. ('s-Gravenhage: Nijhoff, 1879).↩

- J. G. F. Riedel, De sluik-en kroesharige rassen tusschen Selebes en Papua (Gravenhage: M. Nijhoff, 1886).↩

- F. S. A. de Clercq, Bijdragen tot de kennis der residentie Ternate (Leiden: Brill, 1890).↩

- https://www.eyefilm.nl/en/taxonomy/term/6397↩

Sonic City - YouTube links March 19, 2021 09:51

Our new book, Sonic City: Making Rock Music and Urban Life in Singapore, is an ethnography of noise-making centered around a community of people who make rock music within the constraints of urban life in Singapore. When author Steve Ferzacca arrived in Singapore in 2011 to work as a researcher, he did not expect to get involved in the local music scene - but that is exactly what happened.

Ferzacca refers to Sonic City as a "sonic ethnography", since sound, music genres, and music instruments tell stories as much as people do. So what better complement to the book than to see the noise-making in action? The author and his Singapore bandmates/ethnographic subjects can be seen in action on stage in Singapore and Vietnam at the following YouTube links:

https://youtu.be/oMDhBBtbAEE. Blues 77: Route 66 over Saigon. Published July 14, 2013.https://youtu.be/H3gVR8P9zf0. Guitar 77: Steve and Kiang jam “‘Stormy Monday.”’ Film by Sun Jung (1/2012). Published February 27, 2012

https://youtu.be/BxMsUHmeJyE. Blues 77, “Shiok-Lah”, The Hood, May 26, 2012.

https://youtu.be/2uPqZm4-a0U). Blues 77, “Hendrixing”, Ho Chi Minh City, 2014.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9CiA4MdjtRU&list=UUDwKnqMO9YQT392GPwnxZCA. lo hei celebration: Peninsula Shopping Center Singapore.

https://youtu.be/O6dx02SPLhM. “Duke” with opening monologue. November 6, 2015.

https://youtu.be/HxkOF1pYsH4. “Can’t Complain” July 7, 2017.

https://youtu.be/YUJkq1nq5BA. Blues 77, “On the (Doghouse) Floor,” Red Noodle, Singapore, 2016.

https://youtu.be/QFGgPeLI1Cg. Blues 77, “Haiyan,” Red Noodle, Singapore, 2016.

https://youtu.be/AuJ7CZhuTX8. Blues 77, “I’m a Man,” Red Noodle, Singapore, 2016.

https://youtu.be/_nSjP15oQAE. Blues 77, “Hey Now,” Red Noodle, Singapore, 2016.

https://youtu.be/-e8LgJo57QY. Blues 77, “Yangon,” Red Noodle, Singapore, 2016.

https://youtu.be/_cH1pFEWcAg. Blues 77, “You Stay,” Red Noodle, Singapore, 2016.

https://youtu.be/NVa5AUERFjM. Blues 77, “Going Crazy,” Red Noodle, Singapore, 2016.

NUS Press and Covid-19 April 2, 2020 17:50

During the first part of Phase 3 reopening, we were only allowing pick-up of orders for a few hours each day to minimise contact. As Singapore's Covid-19 response continues to be strong, we are now welcoming customers to pick up their online orders from Mon-Fri 9:00 am - 5:30 pm, and are also open for walk-in customers on all weekdays. Another exciting development this year is you can now pay for your books using payWave/payLah etc. when you buy from our store.

We look forward to meeting you. Have a great semester ahead.

NUS Press

---

UPDATED November 13 2020: We are now open for self-collection of online orders from Monday to Friday between 2:00-4:30 pm.

We are happy to announce that we are open for self-collection of online orders again!

In the interest of minimising contact, our customers can collect their orders made on the NUS Press website from Monday to Friday between 2:00pm to 4:30pm only. As usual, please wait for an email from us letting you know that your order is ready for pick-up before you come down to our office. Do make sure to check in by scanning the QR code pasted on our door using the TraceTogether app.

Remembering Ann Wee December 12, 2019 18:31

We received the news on December 11th that Ann Wee had passed away that day, aged 93. She was last in the office a few weeks earlier to chat about the sequel she was writing to her 2017 memoir with NUS Press, A Tiger Remembers.

Ann was a cheerful and inspiring presence to all of us at the press. More than being a delightful author to work with, and a frequent attendee of our book launches and events, she was an inspiring model of how to live: seeking to cross cultural borders, moving out of her comfort zone, first observing carefully, then seeking to help, rarely judging, always ready to learn. An Older Person With Attitude, she was the very opposite of preachy:

“When some elderly person claims that, by virtue of his being old he also has wisdom to share, run for cover. He is almost guaranteed to be on the verge of bombarding you with his opinions, which by virtue of his immodest claim, you can be almost certain will be a collection of personal biases and prejudice.

”I have said ‘he’, and it is true that I have met this more often in older men. But what of the occasional older woman with this self delusion? Watch out! She has the Queen Bee Syndrome, and the rest of us in that hive had better stop buzzing around and listen....”

Ann had a presence for sure, but she was was never Queen Bee.

When asked about her memoir, I am apt to say that it is the single best book I know for appreciating Singapore’s transformation over the last 60 years. That might be quite a claim for such a slim and personal volume. Ann certainly knew the statistics and policy narratives of Singapore’s astounding economic development, of its journey from Third World to First. But the stories she tells in her book are stories of people, within their families and social circles, among their colleagues, sometimes in life crisis, sometimes just dealing with the complications of life, work, family or bureaucracy. Hearing these stories is to understand what better education, better health care, better living conditions, expanded opportunity and social change really mean. It yields a far more powerful insight than the one that comes from marveling over Singapore’s changing skyline, impressive as it is.

The single passage of A Tiger Remembers I most admire is Ann’s dedication. Here she does make a judgement, she lets us know what is important to her. You might be tempted to interpret this as a conservative sentiment, even traditional: yet notice how it is tempered with a deep and seemingly so natural understanding of diversity and of difference.

“To the family in all its 101 different shapes and sizes. With its capacity to cope which ranges from truly marvellous to distinctly tatty: still, in one form or another, the best place for most of us to be.”

We will miss Ann!

The Grand Duke, the tiger and the buffalo November 13, 2019 16:54

An extract from Imperial Creatures: Humans and Other Animals in Colonial Singapore, 1819–1942,

by Timothy P Barnard

Chapter Four: Defining Cruelty

In 1872 Alexei Alexandrovich, better known as Grand Duke Alexis, the fifth child of Czar Alexander II of Russia, visited Singapore along with a squadron of naval vessels. His sojourn in the capital of the Straits Settlements was part of a longer diplomatic journey that involved an extended tour of the United States as well as stops in Rio de Janeiro, Cape Town and Batavia, and eventually Hong Kong, Canton and Shanghai. Grand Duke Alexis was headed to Japan, where he was to meet with members of the Meiji government and participate in discussions on Russo-Japanese diplomatic relations. While in Singapore he met with Governor Harry Ord and attended dinners and balls in his honor, amidst surging crowds and all of the trimmings of pomp and circumstance. The presence of foreign royalty brought some life to the colonial port. As one observer opined, it was “an agreeable interlude in the sleepy monotony and sameness which characterizes life in this so-called Paradise of the East.” The visit was originally scheduled for three days, but went so well the Grand Duke extended his stay for over a week, and even made a visit to Melaka.1

One of the highlights of this brief sojourn in the Straits Settlements occurred on 31 August. That morning, accompanied by the Governor and much of the elite of Singapore, Grand Duke Alexis boarded the government steamer Pluto and sailed around the island to the newly founded town of Johor Baru. The visitors alighted at the bungalow of the Maharaja of Johor, Abu Bakar, who was an influential supporter of the British presence in the region. The Johor royal family, Chinese entrepreneurs and the European elite of the port had been closely interlinked since 1819. The grandfather of the Maharaja was the Temenggong of Singapore who had signed the original treaties with Thomas Stamford Raffles and John Crawfurd in 1819 and 1824 respectively, which transferred sovereignty of the island to the British East India Company. Abu Bakar and his father continued to support the colonial government and its policies in the following decades as they expanded their influence and agricultural policies into the southern portions of the Malay Peninsula. The Maharaja eventually became so intertwined with the imperial elite, and their culture, his British friends referred to him as “Albert Baker,” and the visit of the Grand Duke to Johor was part of the larger theater-state of colonial society in Singapore.2

The Maharaja greeted his guests upon their arrival and accompanied them to a large tent in the courtyard of the bungalow, where a sumptuous breakfast was laid out. After the meal and several speeches, everyone retired to an area behind the building, where they saw a large cage consisting of “long poles driven into the ground and tied together with thongs, and made firm by strong cross-pieces at the top.” The Maharaja of Johor was about to entertain his guests with a contest between a “royal tiger and a buffalo bull.”3

Such spectacles were commonly staged in royal houses throughout Southeast Asia in the premodern era. As Anthony Reid states in a survey of such entertainment, “No great feast passed at the courts of Java, Aceh, Siam and Burma without some spectacular fight between elephants, tigers, buffaloes, or lesser animals.” J.F.A. McNair, a Briton who served as Head Engineer for the Straits Settlements and attended the breakfast that morning in Johor, described such events as “the grand national sport” of Malay polities. It was not the first time McNair had attended such a contest in Johor. Only three years earlier, he was present when the Duke of Edinburgh witnessed a similar confrontation—which would have the same outcome—during his visit to the Straits Settlements.4

A curtain divided the cage in half and, after Grand Duke Alexis and the other guests were readied, the two animals were admitted into opposite sides of the pen. As described in a newspaper report:

Beyond the symbolism of such a contest in a Southeast Asian polity, this staged spectacle, held for the elite of the Straits Settlements in 1872, was also a metaphor for a shift in animals and their importance in Singapore. The tiger was no longer much of a concern for residents of the growing port. The jungle had been tamed, its predators destroyed, and in this case even converted into a form of symbolic entertainment. In contrast, the buffalo—or, more specifically its close relative, the bullock—was about to become the most important animal on the island, where it would play a role in transporting peoples and goods while reflecting attitudes towards animals that would reveal many of the permutations of British imperial rule in Southeast Asia as well as the development of colonial Singapore. The bullock thus would play a role in transforming the island during a period when animals provided much of the labor in transporting goods and people throughout the region, and power structures within the colonial government were becoming clearer. This also would be reflected in how humans perceived other animals, and treated them, particularly those that provided labor.

----------------------------------------------

1 CO273/59/10138: Arrival and Departure of Corvette “Sveltana” with Grand Duke Alexis Aboard; Anonymous, “The Grand Duke Alexis at Johore,” ST, 7 Sep. 1872, p. 1; Anonymous, “The Grand Duke Alexis,” ST, 31 Aug. 1871, p. 1; Anonymous, “Untitled,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 7 Sep. 1872, p. 11.

2 R.O. Winstedt, A History of Johore (1365–1941) (Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1992), p. 137; Carl A. Trocki, Prince of Pirates: The Temenggongs and the Development of Johor and Singapore, 1784–1885 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2007), pp. 128–60; Anonymous, “She Cannot Sue the Sultan,” The Chicago Sunday Tribune, 5 Nov. 1893, p. 1; Anonymous, “The Grand Duke Alexis at Johore.”

3 Anonymous, “The Grand Duke Alexis at Johore.”

4 J.F.A. McNair, Perak and the Malays (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1972), pp. 266–8; Boomgaard, Frontiers of Fear, p. 14; Reid, Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680. Volume One, p. 183.

5 Anonymous, “The Grand Duke Alexis at Johore.”

6 Anonymous, “The Grand Duke Alexis at Johore”; Reid, Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, Volume One, pp. 183–91; Boomgaard, Frontiers of Fear, pp. 146–66.

Enjoyed this excerpt? Buy the book here!

Southeast Asian Anthropologies now available Open Access! October 15, 2019 16:27

What is the state of anthropology in Southeast Asia? How are Southeast Asians teaching and practicing the discipline, given its origins in colonial knowledge projects and the diverse paths of nation-building undertaken by the countries in the region?

NUS Press is proud to announce that an important new publication exploring these and other questions, Southeast Asian Anthropologies: National Traditions and Transnational Practices — edited by Eric C. Thompson and Vineeta Sinha — is now available as an open access title, free of charge for scholars and students in Southeast Asia and beyond. This is thanks to NUS Press’ participation in the Knowledge Unlatched project, which works with academic libraries around the world to unlock funds to make important publications open access.

The project is more than a publication; it is also a means of deepening networks across the region, through an initial series of book-planning workshops and most recently, a series of book launching events in Singapore, Jakarta, and Yogyakarta, with further events planned in the Visayas, Manila, and Kuala Lumpur.

The full text of the book can be downloaded here.

Published earlier this year in paperback, Anthropologies reflects ongoing endeavours to strengthen critical scholarship within Southeast Asian anthropology while seeking to consolidate efforts of teaching, research, and conceptualisation via local and transnational networks.

The project sought to bring practicing anthropologists from across the region together and into conversation with each other. The joint publication eventually materialized from a variety of disciplinary contributions. The first section of the book details the making of national anthropological traditions: the role of anthropology in producing “Filipino” identities in the Philippines (Canuday and Porio, Ch. 1), the struggle for institutionalization in Cambodia (Peou, Ch. 2), and a critical re-examination of Soviet and Western influences on contemporary Vietnamese anthropology (Nguyen, Ch. 3).

Chapters Four to Six shed light on the everyday challenges of conducting anthropological research in specific communities. These include maritime anthropology in the Philippines (Mangahas and Rodriguez-Roldan, Ch. 4), ethnicity and race studies in multi-ethnic Malaysia (Yeoh, Ch. 5), and the shifting institutional and intellectual pressures facing anthropologists in Singapore (Sinha, Ch.6).

The final third of the volume highlights the increasing significance of transnational dimensions in anthropological practice: the development of a “Borneo” anthropology that cuts across three nation-states on one island (King and Zawawi, Ch. 7), the construction of selves and others by Indonesian anthropologists within and beyond the border (Winarto and Pirous, Ch. 8), the opening up and diversification of both theory and practice in Vietnam (Dang, Ch. 9), and the role of Thai scholarship in transnational research (Tosakul, Ch. 10).

Since the book’s publication, meetings, roundtables, and launch events have prompted lively discussions surrounding the state of and prospects for anthropology across Southeast Asia. This volume, then, is by no means intended as the last word, nor does it begin to cover the breadth of exciting and important work being done across the region. We can only hope that it will serve as catalyst for an explosion of growth, interest, and visibility in the traditions and practices that the editors have strived to illuminate.

Anthropologies is one of a number of recent NUS Press efforts to provide the widest possible access to Southeast Asian scholarship while ensuring the quality and sustainability of high value-added publishing. The pioneering journal Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia went open access, beginning with volume three, earlier this year.

Other NUS Press OA projects include Southeast Asia in the Ming Shi-lu, a shared database containing all references to Southeast Asia within the Ming Dynasty reign annals; and the Southeast Asian Site Reports series, a project to develop an appropriate format for the publishing of archaeological reports, many of which include large datasets as well as visual material.

Prizes and Summer Conferences - building to Berlin... July 25, 2019 13:59

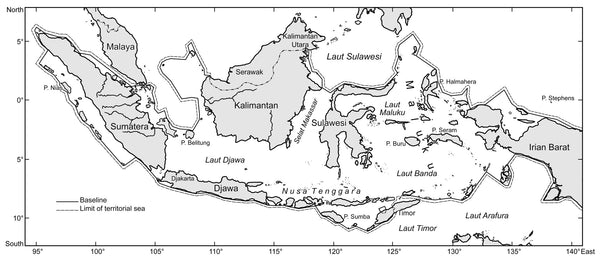

Congratulations to John Butcher and Bob Elson for winning the "Ground-breaking Subject Matter" Accolade in the ICAS 2019 Book Prize competition for their Sovereignty and the Sea: How Indonesia Became an Archipelagic State.

And shortly after that pleasant news, we heard that two of our books were shortlisted for the 2019 EuroSEAS Prizes, one in humanities and one for social sciences. Congrats to Chua Beng Huat for being shortlisted in the social sciences for his Liberalism disavowed: Communitarianism and state capitalism in Singapore, and Lisandro Claudio in the humanities for his Liberalism and the Postcolony: Thinking the State in 20th-Century Philippines.

We're looking forward to hearing more at the 2019 EuroSEAS conference, to be held in Berlin from September 10th to 13th. Do be in touch if you would like to meet up!

Five Minutes with Samuel Ling Wei Chan May 15, 2019 09:42

I n April this year, Dr Samuel Ling Wei Chan published "Aristocracy of Armed Talent, The Military Elite in Singapore". It explores the Singapore Armed Forces by a comprehensive and in-depth examination of its elite leadership: the 170 men (and a very few women) who served or serve as flag officers, that is generals or admirals. How did Singapore build a culture of leadership for its armed forces? What role did the SAF Scholars scheme, introduced in 1971, play in forming this culture?For this edition of Five Minutes With... we turned to noted military expert and journalist David Boey, who conducted this interview and first ran it on his excellent blog on Singapore military matters, Senang Diri. Thanks to David for the interview and for giving us permission to run it on the website.

n April this year, Dr Samuel Ling Wei Chan published "Aristocracy of Armed Talent, The Military Elite in Singapore". It explores the Singapore Armed Forces by a comprehensive and in-depth examination of its elite leadership: the 170 men (and a very few women) who served or serve as flag officers, that is generals or admirals. How did Singapore build a culture of leadership for its armed forces? What role did the SAF Scholars scheme, introduced in 1971, play in forming this culture?For this edition of Five Minutes With... we turned to noted military expert and journalist David Boey, who conducted this interview and first ran it on his excellent blog on Singapore military matters, Senang Diri. Thanks to David for the interview and for giving us permission to run it on the website.

How long did it take you to write the book?

The book is a revised and updated edition of my PhD thesis. I started my studies in March 2011 but by February 2012 it was apparent that my initial topic (on military education in Australia and the US) was not tenable.

What made you press on with research on the SAF despite initial hurdles?

It was a challenge to complete a puzzle and I was focused on the task at hand. The topic is interesting to me, both in academic and general terms.

What was the most challenging aspect of the research for this book?

The most challenging aspects were access to information in terms of open source material and interviews for the specific questions that I had in mind.

How did you go about resolving the challenge(s)?

The 28 interviews were great and a blessing in terms of being able to get the work done.

Which chapter did you enjoy researching/writing most?

I must say I enjoyed them all due to the variation, focus, and information in each of the chapters.

What are the takeaways you hope the reader will glean from the book?

To appreciate the SAF in its entirety, both the good, the quirky, and the not so good.

Call for Manuscripts - Art and Archaeology of Southeast Asia March 20, 2019 22:00

A new book series reflecting the focus of the Southeast Asian Art Academic Programme at SOAS University of London, namely the study of Southeast Asian Buddhist and Hindu art and architecture from ancient to pre-modern times, including study of the built environment, sculpture, painting, illustrated texts, textiles and other tangible or visual representations, along with the written word related to these, and archaeological, museum and cultural heritage studies.

Series Editors:

Ashley Thompson & Pamela Corey

Series Editorial Committee:

Claudine Bautze-Picron

Arlo Griffiths

Heng Piphal

Jinah Kim

Marijke Klokke

Christian Luczanits

Pierre-Yves Manguin

John Miksic

TK Sabapathy

Rasmi Shoocondej

Siyonn Sophearith

Tran Ky Phuong

Louise Tythacott

Call for Manuscripts

All editorial correspondences should be directed to

Ashley Thompson (at50@soas.ac.uk)

NUS Press Submissions (schoppert@nus.edu.sg)

This series is produced in partnership with

Who is this Jacques de Coutre the Prime Minister speaks of? January 30, 2019 11:01

From Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong's speech launching the Singapore Bicentennial: "Around 1630, two centuries before Stamford Raffles, de Coutre proposed to the King of Spain to build a fortress in Singapore, because of its strategic location. Had the King accepted de Coutre’s proposal, Singapore might have become a Spanish colony, instead of a British one."A Year in the Life of NUS Press July 19, 2018 17:35

It has been a busy and fulfilling year for NUS Press, and as there's three weeks to go before the start of the next term at NUS, we had time to catch our breath and recall our previous year in publishing…

2017

August

(pix courtesy NUS Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences)

On August 14th, Prof Chan Heng Chee, Ambassador-at-Large and member of the NUS Board of Trustees launches Chua Beng Huat’s Liberalism Disavowed: Communitarianism and State Capitalism in Singapore, at the National Library Board’s Pod. We follow this up over the next six weeks with book events at the Kinokuniya Main Store, the Asia Research Institute, and the Head Foundation in Singapore. Read Prof Chan’s remarks in the Inter-Asian Cultural Studies journal, or see the NUS News report of the event. Later that month David Teh’s Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary, launches with events in Bangkok, and Chiang Mai. In the upcoming months we have book talks for Thai Art in Kuala Lumpur, Jogjakarta and Singapore.

September

The simplified Chinese edition of The ASEAN Miracle, by Kishore Mahbubani and Jeffery Sng launches in Beijing, published by Peking University Press. Prof Kishore fields questions from Chinese audiences keen to understand his views on the importance of ASEAN in an era of strategic rebalancing.

October

Kishore Mahbubani speaks on The ASEAN Miracle at the Asia Society, New York, and the Harvard Asian Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Later in the month he launches the Kompas Gramedia Indonesian edition before an enormous audience of 5000 students of international relations.

November

The ASEAN Miracle continues to attract interest: The book is featured at the international StoryDrive Asia conference by Singapore’s Intellectual Property Office as an example of effective licensing of copyrights across borders. NUS Press has signed deals for 12 translations and co-editions in the ASEAN countries, China, India, Taiwan, Japan and Italy.

December

ArtForum, New York, names David Teh’s Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary one of its books of the year, and it gets a thorough review in Art in America. Contemporary Indonesian Art: Artists, Art Spaces, and Collectors, by Yvonne Spielmann is named a book of the year by Art & Asia Pacific. The next month we announce our partnership with the Singapore Art Museum for Writing the Modern: Selected Texts on Art & Art History in Singapore, Malaysia & Southeast Asia, by T.K. Sabapathy, and the NTU Center for Contemporary Art for Place.Labour.Capital. Our art list is truly up and running…

2018January

Three NUS Press books were shortlisted for the Singapore History Prize, and the first prize, worth S$50,000, goes to John N Miksic for his Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, published by NUS Press with the National Museum of Singapore. The Jury is composed of Peter Coclanis, Kishore Mahbubani, Claire Chiang and Wang Gungwu (as seen in the photo above, with John Miksic in the middle).

Prof Wang Gungwu, Chair of the Jury Panel, says, “With this book, Prof Miksic has laid the foundations for a fundamental reinterpretation of the history of Singapore and its place in the larger Asian context, bringing colour and definition to a whole new chapter of the Singaporean identity.”

Also shortlisted are Nature’s Colony: Empire, Nation and Environment in the Singapore Botanic Gardens, by Timothy P Barnard, and Squatters into Citizens: the 1961 Bukit Ho Swee Fire and the Making of Modern Singapore, by Loh Kah Seng.

February

The King of Spain writes a letter commemorating 50 years Singapore-Spain diplomatic relations, but looking back to 400 years of interaction, citing the Jacques de Coutre’s Singapore and Johor 1594-c. 1625 as evidence. We published the book in 2015. There’s a citation we didn’t anticipate!March

March 20th, President of Singapore and Chancellor of NUS, Halimah Yaacob, launches Breast Cancer Meanings: Journey Across Asia at a gala fund-raising dinner. That weekend, Peter and Paul fly to the US to attend the Association for Asian Studies meeting, where Paul chairs a panel he organised on Academic Journals and the Publishing Process, and Peter is the only publisher represented at the Digital Technologies in Asian Studies Working Group meeting. Meanwhile, back in Singapore, Cherian George draws a crowd of hundreds for a talk at NUS U-Town on censorship. Our team is there, selling his books, including his latest published by our colleagues at MIT Press.

April

Tim P Barnard’s history of the Singapore Botanical Gardens is reviewed in the Times Literary Supplement, marking our debut in that journal’s review section. Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit’s edited volume - Unequal Thailand gets a super review the Journal of Asian Studies, which says it "should be read by all…who have an interest in contemporary Thai politics and political economy…”

May

Stefan Huebner’s Pan-Asian Sports and the Emergence of Modern Asia, 1913–1974 is published in Japanese translation. A Choice recommended title, Pan-Asian Sports is Stefan’s first book, published by NUS Press in 2016, but it has made a strong impact, 14 book reviews published to date, and another 40 in the works. We launch Writing the Modern at the National Art Gallery in Malaysia, five days after the General Election, and learn that NUS Press author Jomo KS has been named to the Council of Eminent Persons advising Malaysia’s new Prime Minister, Dr Mahathir Mohamad. (We also get some work done on a book project on the election outcome, planned for 2019).

June