How did Indonesia become an Archipelagic State? March 31, 2017 10:00

Until the middle of the 1950s nearly all the waters lying between the islands of Indonesia were as open to the ships of all nations as were the waters in the middle of the great oceans. These waters belonged to no state nor did any state claim any form of jurisdiction over them. As a consequence, Indonesia was made up of hundreds of pieces of territory separated from one another by high seas. Then, suddenly, on 13 December 1957, the cabinet of Prime Minister Djuanda Kartawidjaja declared that the Indonesian government had “absolute sovereignty” over all the waters lying within straight baselines drawn between the outermost islands of Indonesia.

How, in the face of powerful global opposition, did Indonesia  eventually gain recognition of what became known as the archipelagic state concept? That is the story told by John G. Butcher and R.E. Elson’s Sovereignty and the Sea: How Indonesia Became an Archipelgaic State.

eventually gain recognition of what became known as the archipelagic state concept? That is the story told by John G. Butcher and R.E. Elson’s Sovereignty and the Sea: How Indonesia Became an Archipelgaic State.

Here is an excerpt from the book:

In an atmosphere of crisis and extreme anti-Dutch feelings Djuanda’s cabinet met on the night of Friday, 13 December 1957. The meeting began by discussing the political situation inside Indonesia and President Sukarno’s health. It then, according to Danusaputro’s account, turned its attention to the Dutch “warships cruising ‘the Java Sea and the seas of Eastern Indonesia’”. “Without exception all the discussion was aimed at finding a way to prevent and respond to the Dutch ‘show of force’ so that a great deal of thought focused on how to ‘close’ the Java Sea and other Indonesian seas for Dutch warships.” With this goal very much in mind cabinet then began consideration of the draft law prepared by the interdepartmental committee.

Djuanda Kartawidjaja, the 11th and final Prime Minister of Indonesia (Image credit: Wikimedia Commons).

As best we can reconstruct the sequence of events that evening, Colonel Pirngadi, who was accompanied by staff carrying maps, was then called into the meeting to answer questions about the draft law. Immediately after Pirngadi emerged Mochtar was asked to enter the cabinet chamber. As he was about to go in he was waylaid at the door by Chairul Saleh. Chairul had suddenly had the idea that Indonesia’s territorial sea should be 17 miles wide, since seventeen was a “sacred number” for Indonesia, which declared its independence on 17 August 1945, but he abandoned it after Mochtar insisted that the government would have enough trouble defending 12 miles. Once Mochtar had finally entered the cabinet chamber, Djuanda asked him to explain the difference between straight baselines and normal baselines and then asked him a series of questions about the straight baselines on the map he had prepared for Chairul Saleh.

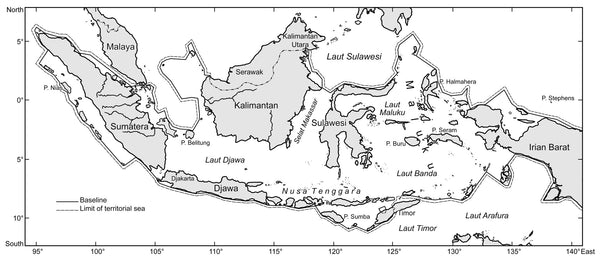

Indonesian waters according to the map accompanying Law No. 4 of 1960. This map has been redrawn from the map accompanying Law No. 4 (Full image credit is available on p. 502 of the book).

After Mochtar left the chamber cabinet began debate. When the ministers concluded that the draft law could not possibly provide a response to the “Dutch actions” they shifted their attention to the declaration being sponsored by Chairul. There followed a “lively and deep exchange of views” about the consequences of making this declaration. The ministers considered the ICJ’s ruling in the Anglo-Norwegian Fisheries case, the Philippine example, and the discussion the ILC had had regarding article 10 of its draft convention. The majority of ministers believed that the declaration would not only meet the government’s needs at that particular time but also protect Indonesia’s interests in the long term.

Ministers were apparently fully aware of the reasons for the interdepartmental committee’s rejection of the “point to point” concept for, according to Danusaputro, some highlighted the great burden that implementing the declaration would place on the government, but this did not dissuade them from believing that the declaration provided the best means of achieving the government’s objectives. After the discussion broadened into a consideration of a wide range of issues including fisheries Djuanda, “at an extremely critical moment”, proposed that the ministers focus entirely on the basic question of the nature and extent of Indonesia’s maritime jurisdiction and leave discussion of other issues to another time. Cabinet readily agreed. Subsequently, according to Danusaputro,

Discussing the issue of maritime jurisdiction in connection with the issue of the “Dutch demonstration of military might” and “the undermining caused by regional rebellion”, PM Djuanda advanced the concept that the “archipelago principle” be applied to the “Indonesian archipelago” with all its consequences, and that the determination would be taken in a political manner.

The Indonesian delegation to the United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, Geneva, 1958.

The Indonesian delegation to the United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, Geneva, 1958.

Ahmad Subardjo Djoyoadisuryo is third from left, Mochtar Kusumaatmadja third from right

(Photo credit: Indonesian Spectator, 1 April 1958).

Whatever the ministers had in mind, Indonesian newspapers regarded the declaration as primarily a security measure. There was some confusion about whether the declaration had in fact already given the government new powers. When a reporter asked Djuanda on 14 December whether it meant that the Dutch warships reportedly in “Indonesian waters” were now “violating Indonesia’s territorial sovereignty”, he would only say that the government had yet to issue an interpretation of the declaration on this matter. An unnamed “high official”, however, insisted that even though the government had not yet passed laws implementing the declaration it did indeed have the power to act against foreign ships violating Indonesian sovereignty.

Against the backdrop of speculation about the immediate security implications of the declaration Mochtar went out of his way in a talk he gave on 29 December to counter the view that the declaration had been motivated by Indonesia’s conflict with the Netherlands. While acknowledging that the conflict had “strengthened the feeling that such a change was necessary”, he portrayed it primarily as a step any state with a weak navy, tiny merchant marine, and undeveloped fishing industry would take to protect its interests, a reflection of the unity of Indonesia, and a natural extension of well-established principles in international law. Reasonable though all this seemed to Mochtar himself and the Indonesian government, the maritime powers were outraged, as Indonesians were already beginning to find out.

****

To read more about Sovereignty and the Sea, click here.